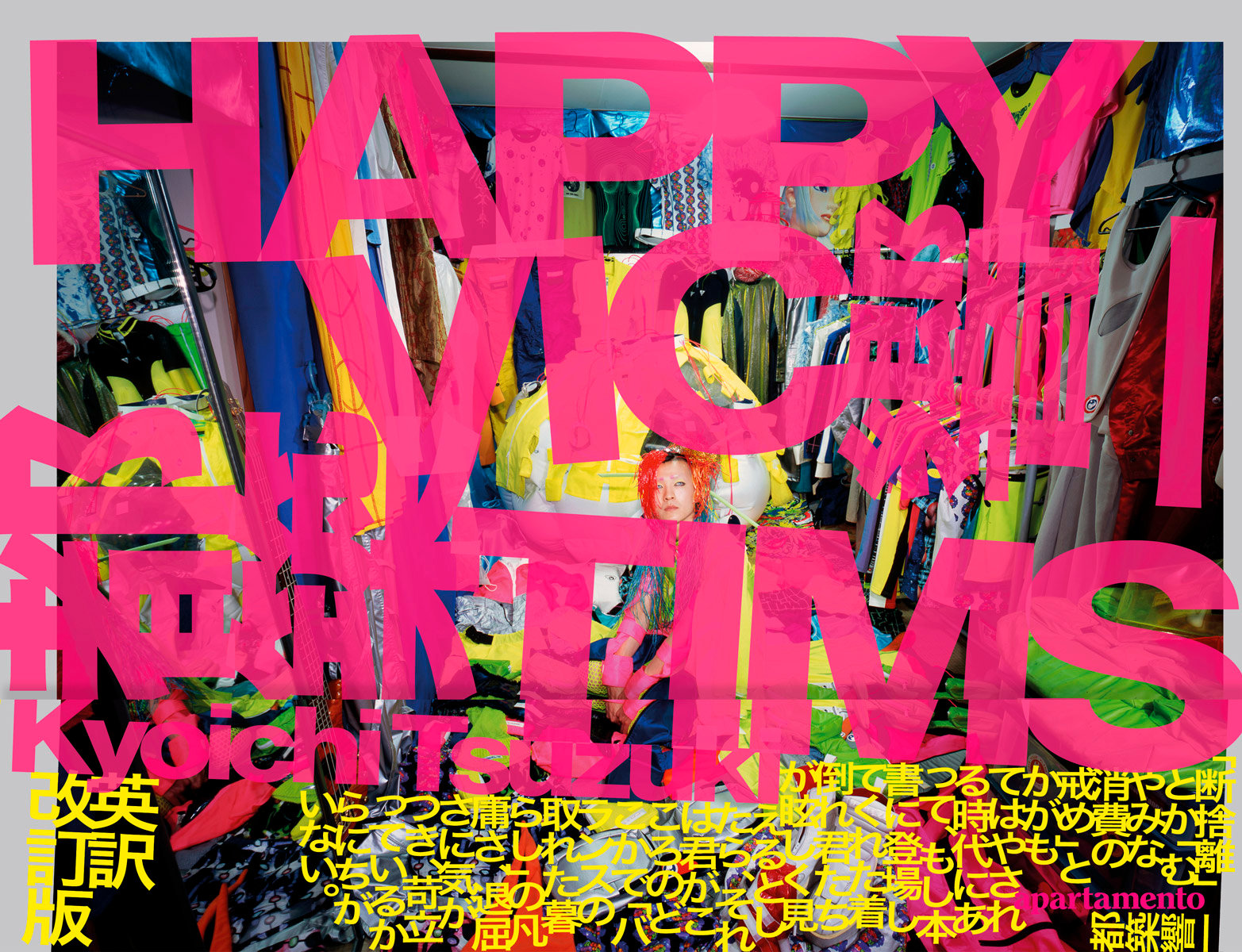

This introduction, written by Isabella Burley of Climax Books, accompanies the reissued edition of Happy Victims by Kyoichi Tsuzuki.

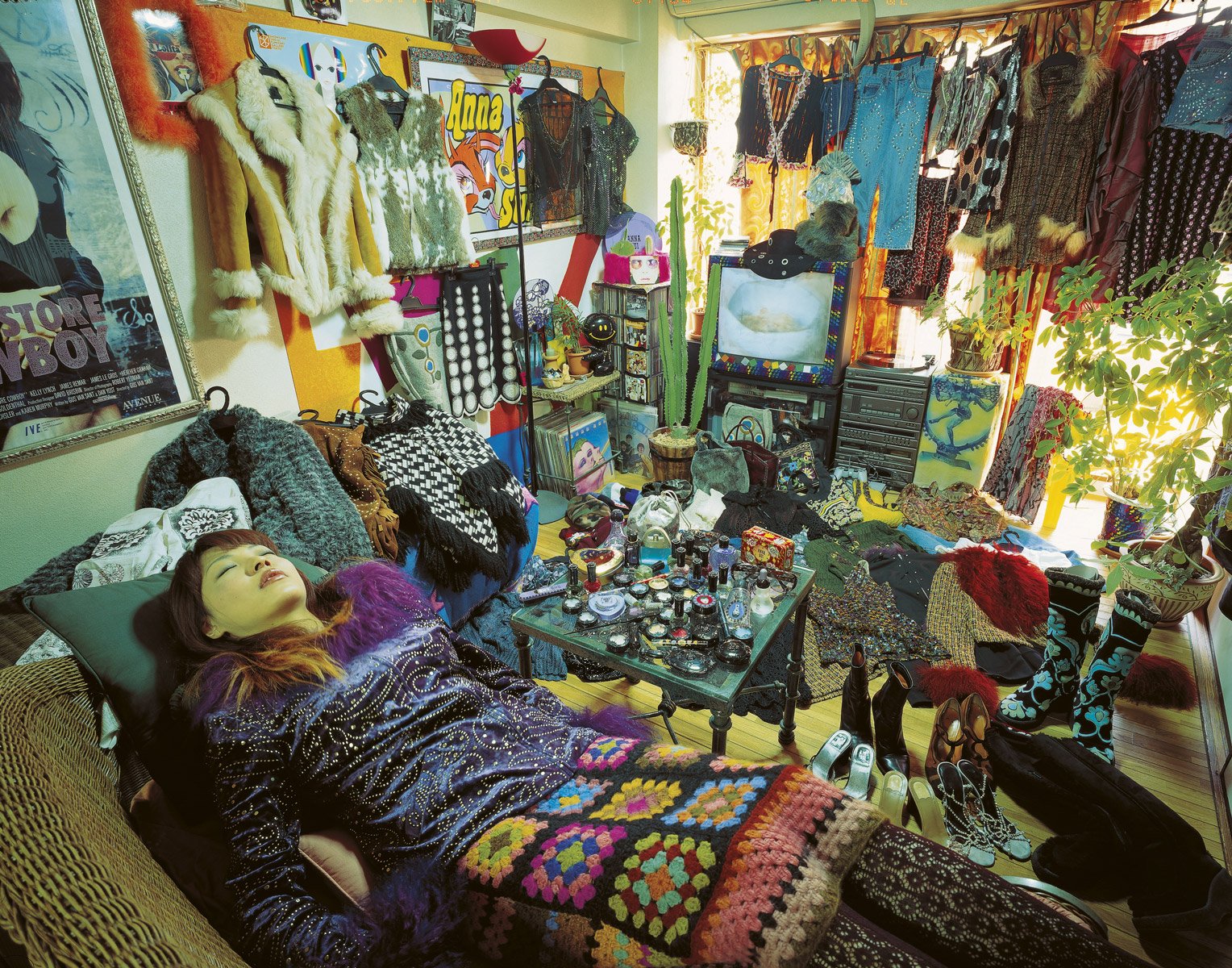

When I was 17 years old, I started working for Comme des Garçons at Dover Street Market, the monumental concept store founded by Rei Kawakubo. It was there, on the concrete shop floor at 17–18 Dover Street in London, that I began to understand the cult following surrounding specific designers—and the people who dedicated their lives to them. It started my own obsession—with designers, objects, books, but also people. The cult of collecting. Ironically, it was also 2008, the same year Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s Happy Victims book was published.

Dover Street Market was the safe space for fashion obsessives. I’m not really sure how it happened, but my teenage years working there quickly became my fashion education. After all, Comme des Garçons, with its own dedicated following (its early adopters were lovingly known as the ‘crows’), has come to represent something subversive and countercultural. It was a place for fashion freaks. We existed outside of the mainstream, and that was exciting. I would wear Junya Watanabe runway pieces to work, including leather platforms that aggressively whipped the floor when I walked. My colleagues would be in head-to-toe Rick Owens or Comme des Garçons collections so extreme they could barely fit through the door (think the AW12 Paper Dolls collection). We would all get stared at on our lunch breaks, secretly thinking how fabulous it was.

close

close