Kyoichi Tsuzuki

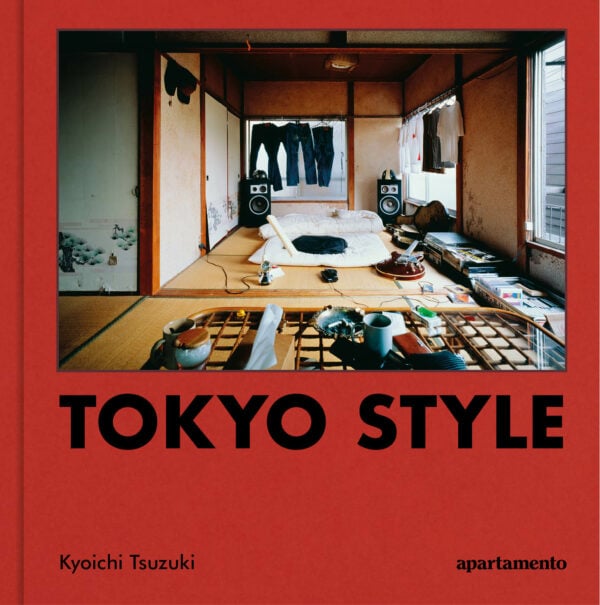

In the early ‘90s, magazine editor Kyoichi Tsuzuki began photographing cramped, cluttered apartments in Tokyo. Threading the city’s dense network of streets on his 50cc Honda scooter, he bounced between the dwellings of friends and strangers, shooting inside their homes with a borrowed large-format camera. These interiors were not the beautiful, minimalist ‘neo-Zen’ spaces depicted in glossy magazines. These were the unruly dens of Tokyo’s young and poor. Friends told him the project was ‘cruel and unusual’, but Tsuzuki knew what he was doing. He had spent the ‘80s as an editor for Popeye and Brutus, two of Japan’s influential youth culture magazines, and had left that industry to explore the worlds turning outside the margins of magazines about ‘good design’. Tsuzuki has now published hundreds of books that upset hierarchies of taste by focusing on topics that oscillate between the sensational and the quotidian: love hotels, decorative African coffins, roadside museums, wax museums, sex museums—the ‘low’ art of amateurs and outsiders. But it all began in 1993 with the publication of his first photo book about cramped apartments, the influential Tokyo Style. This was the same year that Muji opened its largest store to date, a 1,100m2 temple to minimalism, and the same year Issey Miyake launched Pleats Please. Tokyo Style, however, has more in common with another cultural moment from 1993: the release of the film Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II, an ode to ignoble maximalism and playful destruction. At 65, Tsuzuki still views Japan as a messy assemblage, a lively site where chaos gives way to emergence. On a summer morning, in his apartment located between the Imperial Palace and the visual noise of Shinjuku, he talked about the making of Tokyo Style and the difficulty of looking at things beyond the margins of magazines and outside the umbrella of the internet.

Would you ever make another version of Tokyo Style?

No, not again. In the 25 years or so since I made the original, the city has lost its gravity. Back then, if you wanted to become a musician you had to come to Tokyo. Now you can make your own music or website or zine in your countryside town and just release it to the world.

But was the gravity more localised than Tokyo as a whole? It seems most of the apartments you photographed for the book were concentrated around a handful of train lines that flowed out from the centres of the city. I guess these were the places where young people were moving to in the ‘90s.

Yeah, it was just those areas where I had friends.

Were all the people in that first book your friends?

They were friends, or friends of friends, or people who happened to live in the same apartment.

What made these apartments interesting to you?

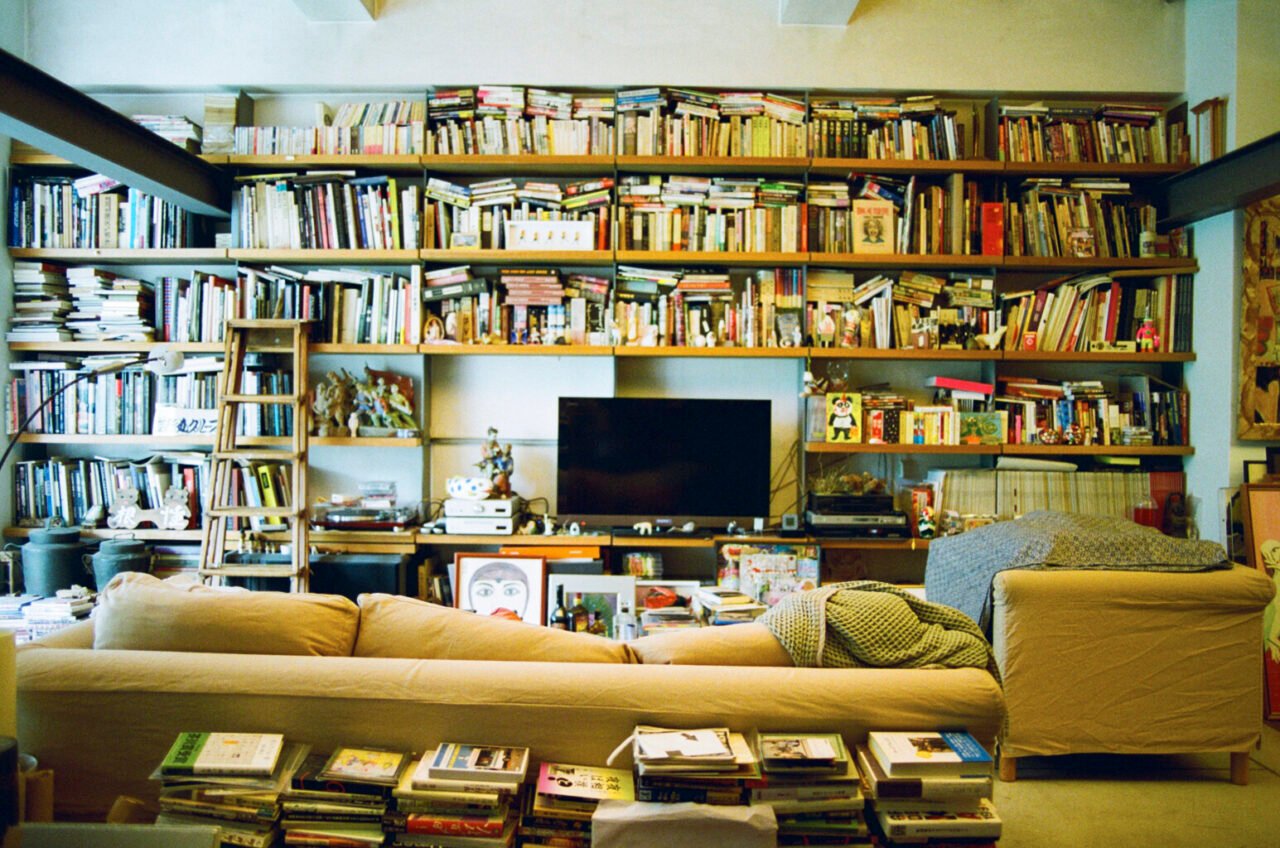

Every apartment is interesting if it’s cheap. Most expensive apartments are boring because they’re all the same, but in small apartments you can’t hide your personality. I thought that if I took photos of 10 apartments, it would be a fun story, but if I took photos of 100 places it might become something, a piece of reality.

This was in the pre-internet era, so how did you meet people and arrange to take your photographs? Was it complicated and difficult to get people comfortable enough to give you access to their homes?

I would typically meet someone in a bar and ask, ‘What kind of place are you living in?’ Then I might ask if I could photograph their room. Once I was inside, I’d ask, ‘Do you have friends around here I can visit, too?’ Sometimes they’d say, ‘Yeah, I know the person who lives next door—let’s go’. But often no one would answer the buzzer, so they might say, ‘I know where the key is, let’s go inside, I’ll tell them later’. Something like that. It was really easy to find places like that.

Incredible.You were basically breaking into people’s homes. The owners are almost always absent from the images, but when you reveal them in some of your later books, such as Universe for Rent or Happy Victims, they are always blurred. Why did you choose to show people like that?

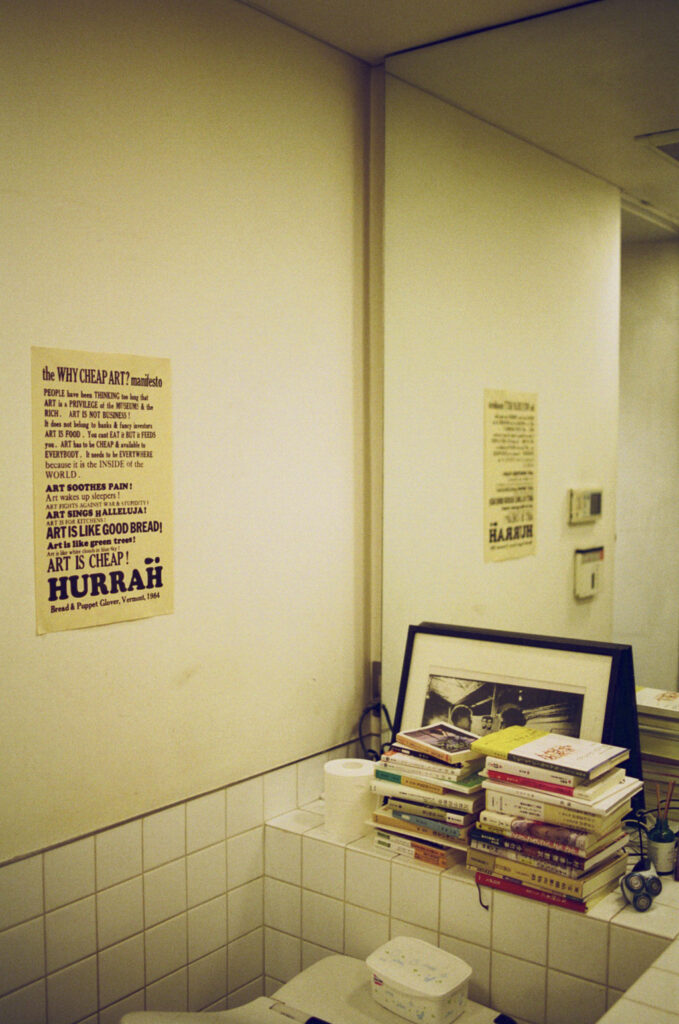

All the photos in Tokyo Style were shot with natural light, so that meant extra-long exposures—usually 30 seconds to a minute. If a person was in the frame and moving, they became like ghosts. For Tokyo Style, I didn’t want people in the shots because you would just look at the person, and it makes you view the space differently. When I started taking photos, I didn’t have equipment or experience, and I didn’t have much money either. I wanted to shoot with a large-format camera, but I didn’t even know how to put the film inside it. All I had was a small lamp, a camera, and my 50cc Honda scooter. I had to put everything between my legs as I rode around.

So many of the spaces are filled to bursting with objects, like the owners are spreading themselves over the walls and floor. Would you say that most of the apartments you shot belonged to young, creative people?

Not even creative, just young and poor. But everyone was like that. If I had to make a book about beautiful Japanese homes it would have been very difficult because no one was living in places like that.

That’s still the image that dominates—that Tokyo interiors are all about minimalism. There was recently an exhibition at the Barbican in London called ‘The Japanese House’. There was recently an exhibition at the Barbican in London called ‘The Japanese House’. The poster for it featured House NA in Koenji, a house designed by Sou Fujimoto that looks like it’s made up of stacked glass boxes. But houses like that are the exception, and even House NA is often filled up with stuff; you can see sometimes when you walk past.

Because it’s not their style; it’s the architect’s style or the interior decorator’s style.

In the introduction to Tokyo Style, you challenged the view that Tokyo is just filled with neo-Zen, simple, and minimal spaces. Do you think this is still the view people have of Tokyo?

I think so. But it’s not a reality, it’s a dream. Just like the recent book by Marie Kondo—the idea that we should try to throw away everything and live simply. Like Marie Kondo’s books about decluttering, we buy those books as a dream, you know, just like you buy a book about Ferraris: you dream about owning one, like you dream about your room being clean. It’s nice; I don’t want to have a negative view of that kind of neo-Zen lifestyle. It’s your choice to live in a cluttered space or live in a simple space. But I don’t like the view that living in a clean, simple space is intellectually superior to living in a small, cluttered space. I don’t like that idea. It’s a choice, like the kind of music you listen to.

You think it’s just taste.

Yes, but people want to make hierarchies out of taste.

Your books are about aesthetics, but, in a way, they’re also about economics. Tokyo Style shows the apartments of young, poor people, as you say, but it came out at a time when people still believed Japan was an especially wealthy nation.

Exactly, but now Tokyo is so much cheaper to live in. Tokyo is becoming one of the cheapest advanced cities in the world. Accommodation isn’t too expensive, and you don’t need to spend money on your safety. That’s a big thing. If you live in the roughest parts of London or New York you could be robbed or worse. But Tokyo doesn’t have bad areas like those cities.

You don’t think there are any bad neighbourhoods in Tokyo?

None at all. The ‘bad’ areas are just cheap to live in.

What about ‘bad’ in the sense of gentrification, in the sense of neighbourhoods going bad, becoming unfamiliar to the people who once lived there? Do you think a similar process is taking place in Tokyo?

Yeah, there is gentrification here, too, but it’s not as heavy as in New York or London. For example, right now in Asakusa, small, old apartments are being replaced with large condos. But one thing that makes Tokyo different to other cities is that we don’t have strict zoning laws here. You can build a factory or an apartment anywhere basically. Soaplands—these erotic bathhouses—and regular apartments are built next to each other. It’s really mixed, and not so tightly controlled. When you go to the most expensive neighbourhoods in Tokyo you can still find small, old apartments as well. There’s nothing like that in Beverly Hills. Most of the cities in the world have clear boundaries between good and bad neighbourhoods. In Tokyo, it’s really mixed.

I want to go back in time a little here and talk about the late ‘80s, the ‘bubble period’ when Japan enjoyed economic prosperity unlike any other time in its history, until the bubble burst in the early ‘90s. Japanese investors bought controlling shares in US institutions like Columbia Pictures and the Rockefeller Group in 1989. There was an article published in the New York Times that year with a headline something like, ‘Japan Buys the Center of New York’. It was a strange time. This was right before you started working on Tokyo Style.

I enjoyed the bubble period. I had a lot of fun. But the bubble shock only affected really wealthy people. I don’t think young people placed much importance on the bubble.

How do you think it affected Japan culturally?

People talk about the bubble period as a very, very bad experience for Japan, but I have a different view: during the bubble Japan was freed from its place in the European cultural hierarchy. If you have money you can buy a van Gogh painting or the Rockefeller Center. I think the bubble crashed existing structures in society: we found out that if we had money we could just buy a castle in Europe, so it changed the mentality of a lot of Japanese people, I think. We didn’t have to feel lower than Western cultures.

A lot of changes hit Tokyo in the ‘90s. I think your books from this period show how old structures were changing shape, but another publication that documented something similar was Shoichi Aoki’s FRUiTS magazine.

FRUiTS is similar because the photographers didn’t take photos of kids dressing exceptionally different; a lot of them just dressed like that normally. These were just kids that did something with their existing clothes, they modified themselves more than the people who only bought high fashion. FRUiTS is also an expression of street reality from that period, I think.

When you were making magazines, as editor of Popeye and Brutus, did you already have the idea of documenting ‘real’, everyday spaces in Japan?

No, with everything I do—from Tokyo Style to Roadside Japan and everything else—I don’t develop a concept. I just start because something seems interesting, and then gradually, little by little, I think about what’s behind the idea.

What was behind the idea for Roadside Japan?

I had been working with young people in Tokyo, and most of them were not born in the city; they came from countryside towns. Back then, you had to come to Tokyo to do something, so these kids had a very negative feeling about their hometowns. I wanted to find the nicer side to these towns. I started to travel, and there were so many strange, interesting roadside attractions. So many countryside towns are like that—they’re not like Kyoto. There’s no shame in being born in a small town.

Roadside Japan is unique because you went out into the countryside, captured a different view of reality, these absurd places, at a moment when most people were focusing on technology and cities.

When I made Roadside Japan, I didn’t know much about the countryside. It was a no-internet period, you couldn’t find websites, you couldn’t expect anything. No GPS. Nothing. There was almost no mobile reception, so I would just drive around with a map and discover these towns by myself. We didn’t know about hihokan, or sex museums, until we found them. This was the mysterious side of Japan.

Is that the reason why these places were appealing to you?

Absolutely. They’re mysterious, but they’re also common. These rural places—love hotels, especially—are so popular. Beautiful buildings in the countryside by Tadao Ando or someone similar are the exception.

Some are so excessive, overdecorated to look like an Italian villa or filled with water features like the set of a kitsch ‘50s sci-fi. Why do you think they’re designed that way?

Love hotels have been like that since the ‘70s. They’re like mini travel destinations. You can’t just go to Venice for half a day, but you can have fun in a hotel that tries to copy that kind of experience. It’s popular culture, love hotels, or hihokan. But some of that is changing; there were many hihokan in Japan 20 or 30 years ago, but now they’ve almost all gone.

Often we assume it’s just traditional culture, crafts, and festivals that are disappearing. But other, more modern things are changing, too. Cabaret. There were so many cabarets in Japan. Cabarets were large places that had hundreds of hostesses and a dance floor and a band. You could drink and dance with hostesses and enjoy the show. They were so popular in the ‘50s and ‘60s; now there are only three cabarets left in Tokyo. In the early ‘60s, at their peak, there were 1,500 cabarets in Tokyo. That’s a part of the popular Showa Period culture we are losing. But another type of bar from the period, the snack, is still going strong.

You mean the kind of bars in Shinjuku’s Golden Gai, tiny drinking holes with only a few seats at the counter that serve nuts or other snacks?

Golden Gai has more standard bars. Real snacks—karaoke snacks—are slowly decreasing, but there are still a lot. There’s a survey in a recently published academic book about snacks, which says there are still 150,000 of them in Japan. Karaoke snacks are easy to run: people come, get drunk, and sing.

When did snacks first appear?

They were made for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics because we expected to have a lot of tourists and the government wanted to close down ambiguous drinking holes, but still provide a place to drink at night. So they made up a new kind of place to drink in: there’s a counter and you sit on one side and the mama-san or girl or boy serves from the other side—they don’t sit with you, side by side.

These spaces might seem special, but they’re really common. There seem to be snacks in almost any Japanese town or village. Love hotels are just as ubiquitous. What do you think makes them special?

Japan has the same kind of hotels everywhere, but love hotels are different because there’s extra decoration on everything. If you live in Paris, you just go to a plain hotel to do the same thing. But when you go to a Japanese love hotel, there’s a button to make the bed rotate or a mirror on the ceiling.

Why do you think that is?

It’s related to the owner’s idea of what ‘service’ is. If a room is plain, it’s not so fun, so maybe they decide to add something else like a rotating bed. When you’re designing anything, there comes a point where you should stop adding to the design. But sometimes in Japan people go beyond that point, putting in extra effort for nothing.

What about somewhere like the Robot Restaurant, which involves a lot of what we’ve been talking about.

It might be overdecorated, but it’s part of an aesthetic in Japan, too. People think Japan is defined only by things like katsura rikyu, a refined style of Kyoto architecture, but there are two sides to it. From the same time period we have the extra-ornamental, colourful Nikko Tosho-gu temple.

There’s a word you use in a caption from Tokyo Style to describe an overdecorated, cluttered room—moreiru—which I think means ‘overflowing’. This adjective applies to a lot of what you’re interested in, from the excessive design of love hotels to the interior of a pachinko parlour. But this isn’t unique to Japan, right?

In Western culture there are so many things that are overdecorated. It’s the same thing here: 21st-century baroque paired with technology might be the Robot Restaurant.

Why do you like that kind of design?

It’s design that puts pressure on you.

When you were making Tokyo Style and Roadside Japan, you had to search and discover everything. What are your thoughts about the way people discover new places today?

There is a huge area that is still off-grid from the internet. I made a book about interesting old people who live alone and are totally outside the internet—a lot of karaoke snack people, too. If you’re old, you don’t need the internet; if you’re only doing business with regulars, you don’t need a website.

And you’re still looking for places outside the internet?

Before I visit a new place I check with Google. If there are lots of hits, I don’t need to go, because someone else has already reported on it.

You mean there’s no point in going?

If it’s been covered, I don’t need to go. If a place has hits on Google, my game is lost.

Grab grab yourself the latest release of the cult classic and continue here for archival footage from Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s, Tokyo Style.