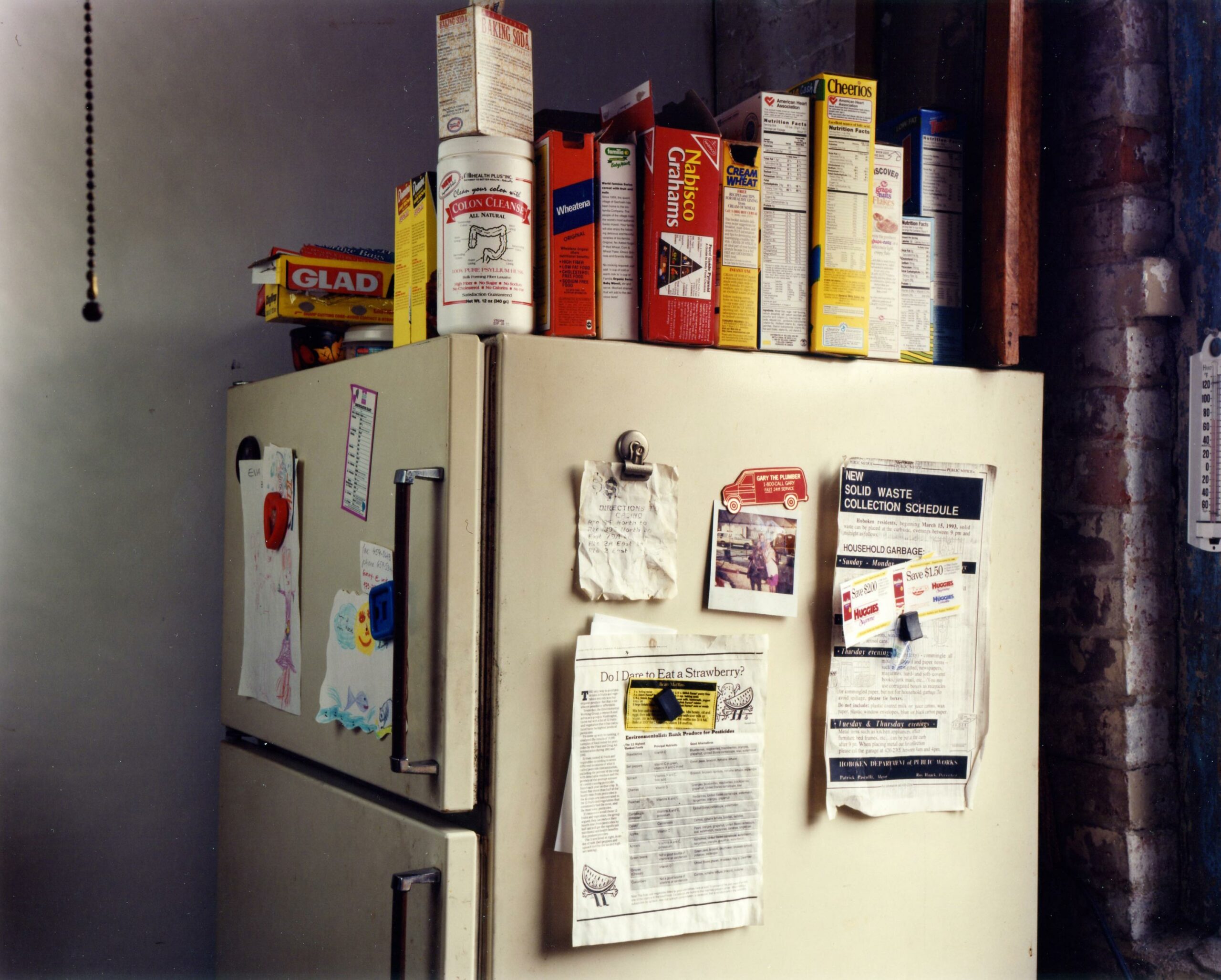

The first time I saw one of Davey’s C-prints was online: a small, low-resolution image of a ceiling light fixture that I zoomed in on until it blurred. The first time I saw one of her films in a museum—Les Goddesses (2011) at the Art Institute of Chicago—I sat for hours scoping out the interior of the artist’s apartment. Admittedly, I was transfixed. Here was Davey, narrating and enacting the role of a flâneur of the home. Same as my mother. Well, same but different, like the cereal boxes on the fridge in Glad and those in our kitchen—same because mass-produced, different because in a different home, with a different floorplan, different inhabitants.

When we examine Davey’s photographs of domestic interiors or watch films like Les Goddesses, we become voyeurs of her candid or at most semi-staged life. We see her dusty books and unpaid bills, the robin’s egg blue of her kitchen walls, picture frames on the floor in the hall, her mismatched table and chairs. Yet we aren’t given enough specificity to psychoanalyse her based on these details, at least not deeply, and not any more than she does in her monologues. Our only task—the only thing our eyes can do—is simply look, look, look.

Our fridge was a top freezer, like Davey’s. Two unequally sized registers, harmonious in their proportions like a Rothko painting. The bottom door was studded with ceramic magnets and pockmarked with peeling stickers; I remember trying to save the stickers by covering them with the magnets. I remember loving the cold smell of the freezer, whose contents I could barely see and had nothing to do with me, like the idea of heaven. I remember mouthing the words on the sides of jam jars in the cold light and on the receipts my mother and I got from the store we ventured out to once a week. It isn’t lost on me that my mother’s main occupations were domestic in nature and that her agoraphobia was exacerbated by—or at least intimately linked to—having a role in the household centred on what Davey calls ‘managing’ the fridge.

When I entered adolescence, we moved to a different house in a different state. There, my desire to explore the town, my insistence on an independent identity, on cleaving from my mother’s private sphere, led to long, excruciating fights. Between the inside and the outside were minefields of negotiation, dark rabbit holes of guilt. Rain was enough of an existential threat to foreclose any discussion of my going out, but as a mute peace offering, my mother stocked the fridge with my favourite ice creams, yoghurts, jams, and preserves. I still associate the tastes of those foods with her.

It is perhaps for all these reasons that I possess a voracious impulse to consume the spaces that others occupy, those pieces of private property made communal. As Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida, ‘The age of photography corresponds precisely to the explosion of the private into the public, or rather into the creation of a new social value, which is the publicity of the private: the private is consumed as such, publicly’. Lacking an image to disseminate, I can only conjure in words the intimations of that lost kitchen in Florida, the blue flowers on the wallpaper, the honey-hued linoleum floors, the light switch that seldom worked, which my mother would call me in to flip as evening crept through, swearing my touch was good luck.

Time has a funny way of congealing what were once forgettable years—as well as periods of suffocating idleness, periods of intense longing—into vivid, almost talismanic images. Just as the temporal metonymy of photography, which flashes fragments of the past into the haze of the present, can make a cluttered refrigerator appear singular and profound, my memories are briefly illuminated when they congregate around the icebox of my childhood home.

close

close