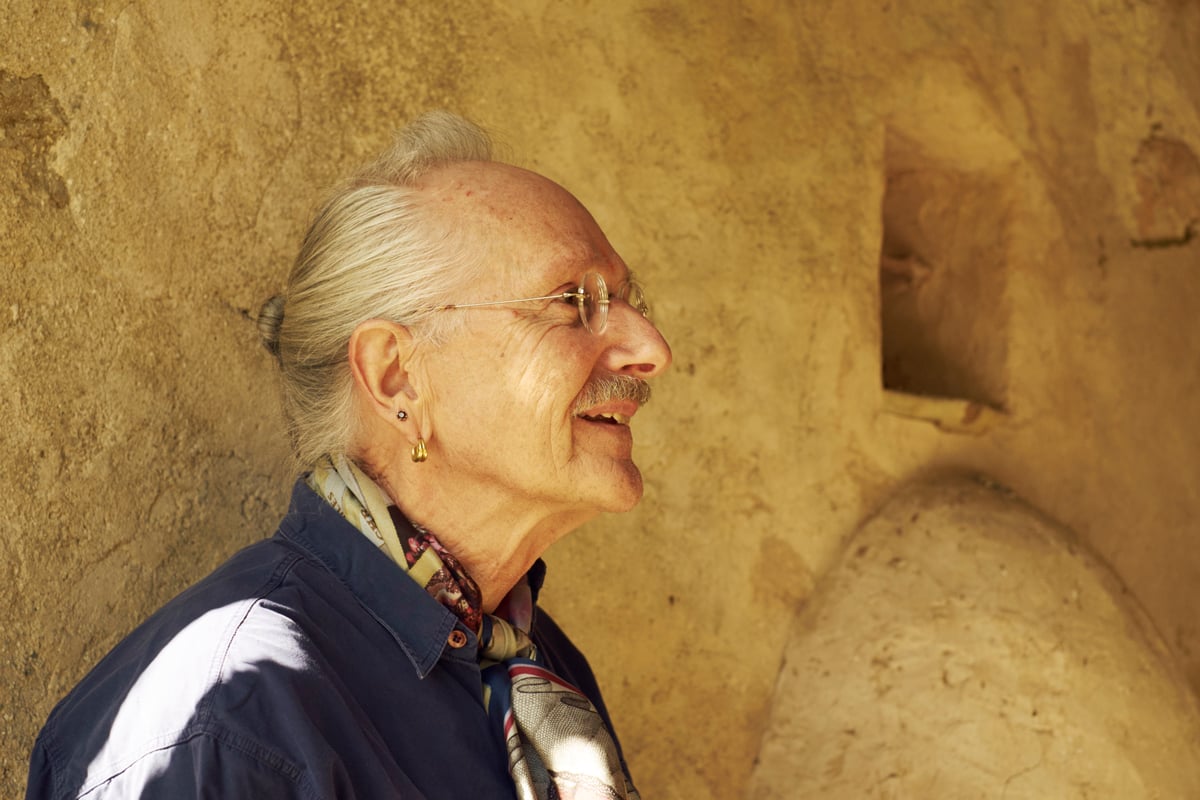

My three books of living room portraits—New York Living Rooms (1998), Paris Living Rooms (2002), and Berlin Living Rooms (2017)—bridge the end of the 20th century and the first quarter of the 21st century. Twenty years! They capture my world, that of the cultural nomenclature of my time, the end of a dying century, and the awakening of a new one. It all started, as I have written many times, when Tina Brown, at the time the editor-in-chief of the New Yorker, commissioned a photo essay. She wanted me to photograph the room where a writer works. I am ashamed to say that it didn’t excite me much, maybe because I had made so many writers’ portraits already. We agreed on the choice of the living room. When the New Yorker pictures were published, the positive reaction surprised me. The interest of a Japanese publishing house gave me the idea of a book. And with the introduction of the New Yorker, the doors of New York opened to my camera.

As I wrote in my introduction to the book, New York Living Rooms is not exactly about interior decoration. Although it represents a special stylistic and aesthetic approach (I used the Polaroid Colorgraph type 691 film for the first time, which provided a full colour positive transparency with accidental and eccentric colours), it is above all a document. No rearranging, no adding of bouquets, no use of flood lights. I approached the living rooms like the people I photographed, making a portrait as close to reality as possible. John Richardson wrote on the back cover of the book jacket that ‘as a photographer, Dominique Nabokov disdains artifice … For Dominique, the truth is all that counts’.

And this then became a guide for the two following books.

Naturally the idea of Paris Living Rooms came to my mind. In those years, New York set the tone, and with New York Living Rooms under my arm, Parisian society welcomed me enthusiastically. The introduction by interior architect Andrée Putman was a sort of coronation for me. And in the blurb for the back cover of the book she wrote, ‘Although those portraits without makeup have a touch of a passport photo, Dominique Nabokov in this photo essay demonstrates a very subtle and conceptual approach which is softened by her technical laissez-faire’.

It took me quite a long time to succeed in producing Berlin Living Rooms. Paris and New York were easier because I lived between the two cities. Berlin necessitated a longer stay that would be costly and more difficult to organise for the third and final instalment in the trilogy. Yet it became reality when I received an invitation from the American Academy in Berlin to spend a few months in the German capital. I knew it was my last chance to make Berlin Living Rooms. I could not use the Polaroid Colorgraph type 691 film because it had been discontinued, so I decided to use a black and white 35mm film—Ilford FP4 Plus—to symbolically recreate the expressionist style of Berlin’s photography and movies from the ‘30s, a period that fascinates me, as I wrote in my introduction for the book.

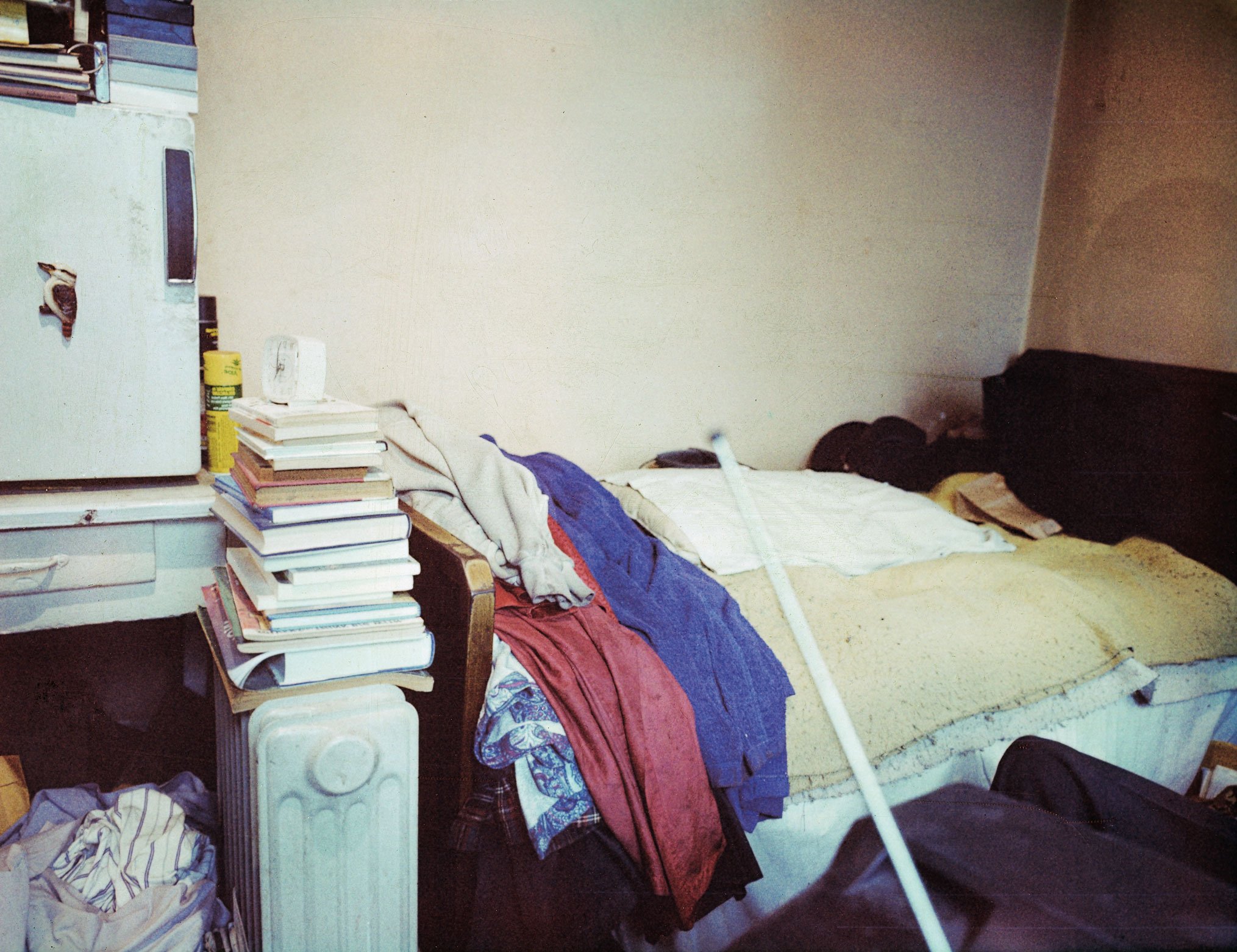

I want to specify that I did not engage in the living rooms trilogy project as in a People magazine adventure. It was very clear in my mind that this would be a book of portraits which had to be judged strictly on the visual quality of the portraits. But, of course, I cannot deny that I thoroughly enjoyed the voyeuristic adventure of opening the doors of the various doers of the cultural nomenclature of my three chosen cities. Vivid images remain in my memory of the places and their owners, although most of the time they were absent when I did the shooting: the artist Louise Bourgeois, in Chelsea, crossing the room all the time in front of the camera when I was adjusting my lens; being alone in the heavy silence of the Paris mausoleum living room of Yves Saint Laurent, which felt like being in the tomb of a pharaoh of our time; the poet Quentin Crisp refusing on the day of an intense heatwave in the East Village to leave his room (he had only one) and hiding in a corner when I took the shot. Also the unique room in Soho (six floors up) of the dandy-witty-patrician Taylor Mead, man about Andy Warhol world, and being suffocated by the smell of his invisible 16 cats. The photo session was done in a second!

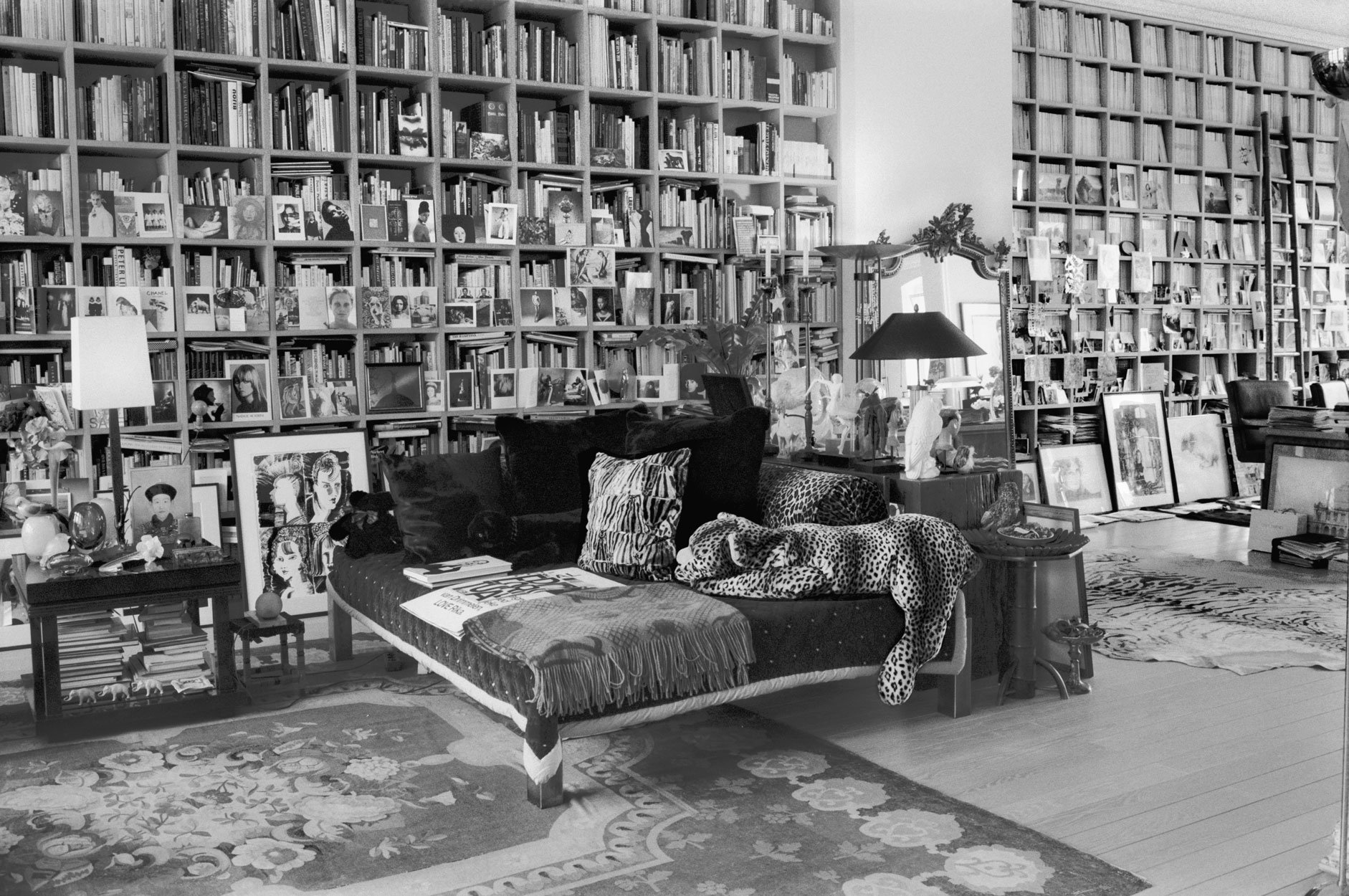

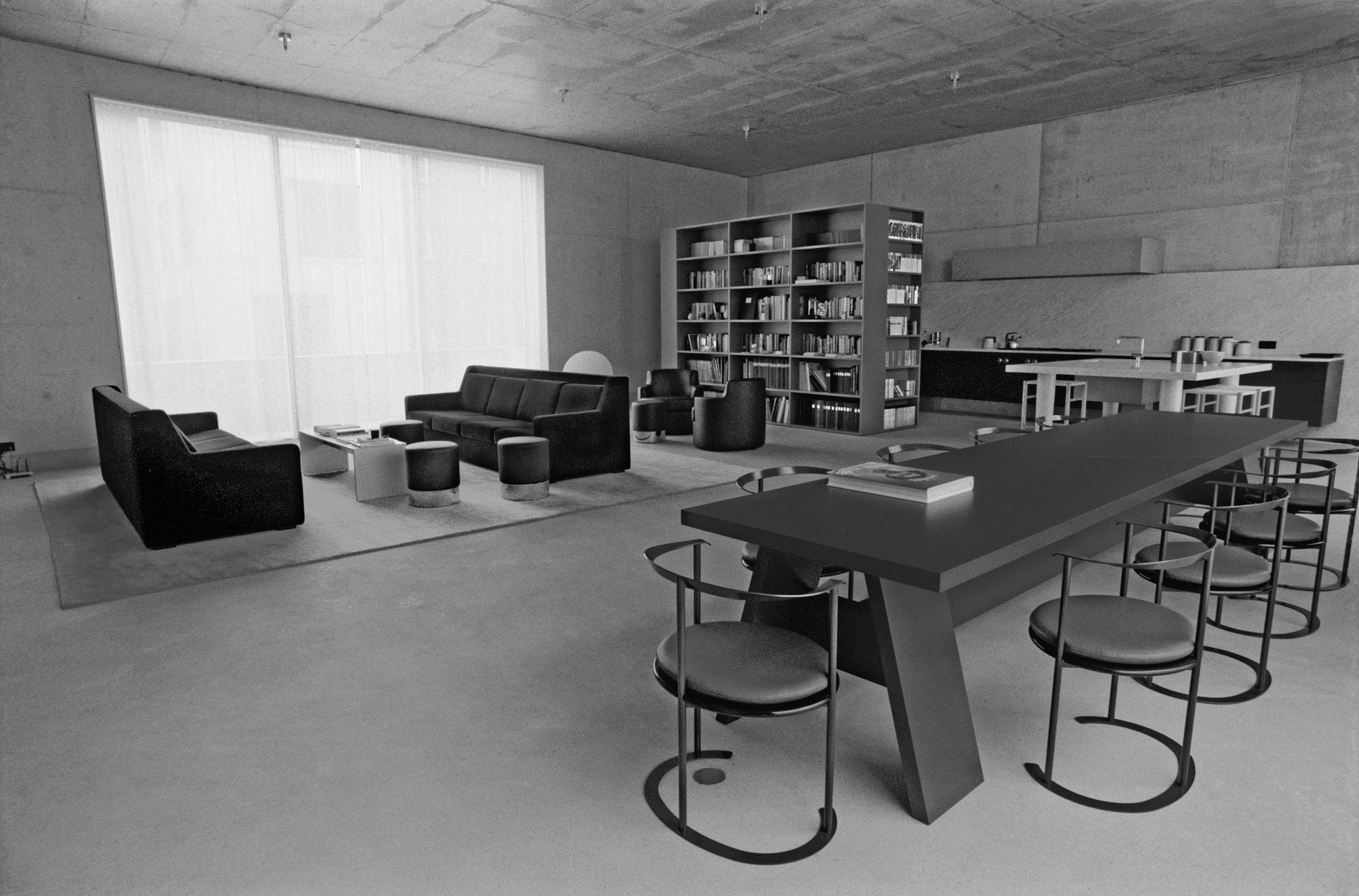

The surprise of discovering the Paris living room of femme fatale actress Jeanne Moreau, with a desk in the centre like the president of the United States. Or arriving a day too early at the home of Angelica Blechschmidt, in Potsdam, and if she had not let me in so nicely I would have missed the most extraordinary, original, and beautiful living room belonging to that quite unique fashion journalist who never threw away any books, documents, or printing material. The chic utilitarian minimalist living room in Neukölln of Fabian Ebeling, opposed to the chic minimalist ‘collectors in’ living room of Benita Yon-von Dehn and Marcel Yon in Potsdam. The strikingly avant-garde, panoramic, concrete-clad living room in Mitte of the English architect David Chipperfield, where I felt like a dwarf in front of the huge table where a huge photo book on Queen Elizabeth II lay, distracting all my attention. The Crown must have been already in the air!

To summarise, the general feeling I get from the three metropolises—New York, Paris, and Berlin—where I have lived the most and which I like the most, is that in New York anything goes, in Paris le bourgeois still rules, and Berlin is a work in progress.

close

close