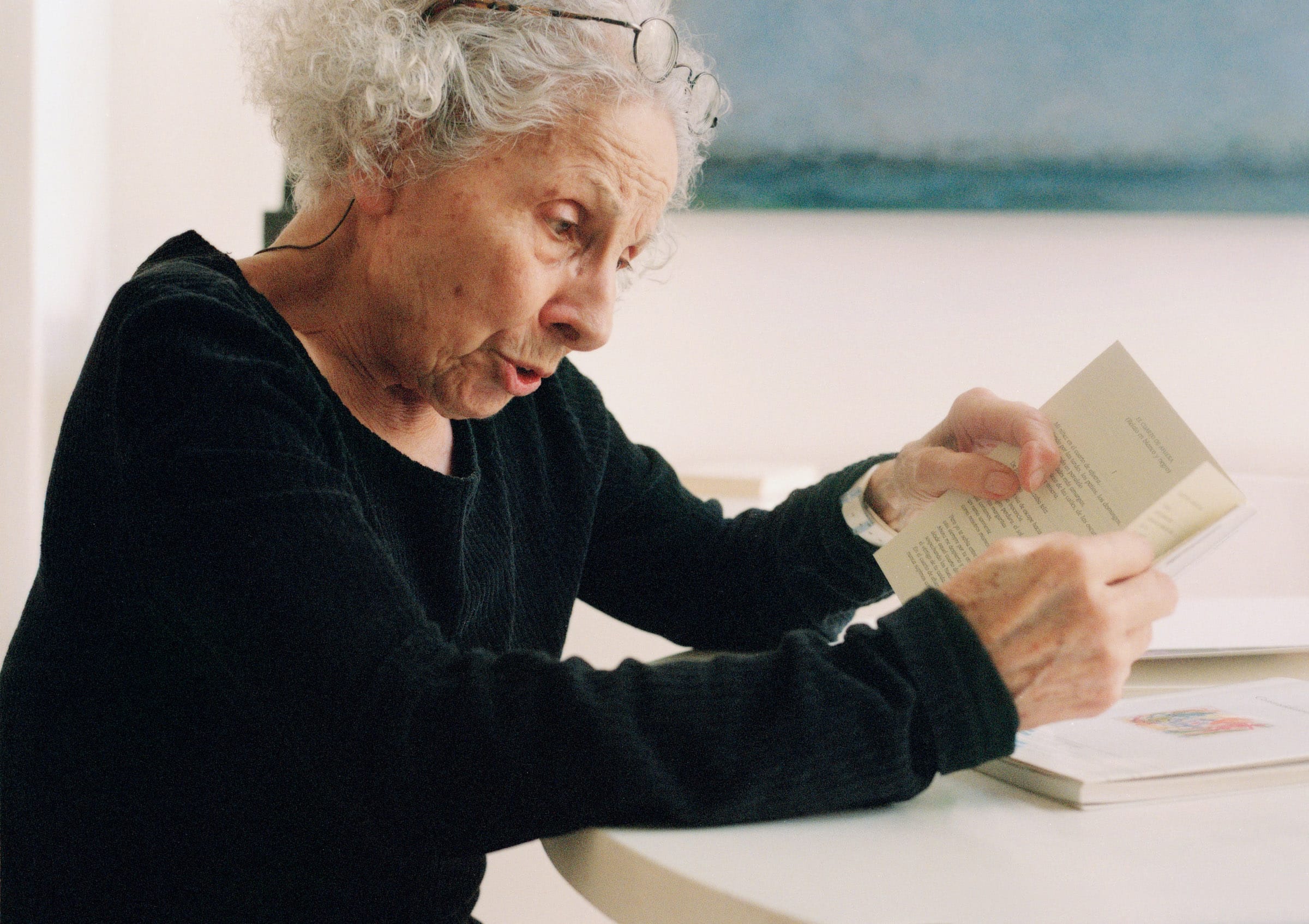

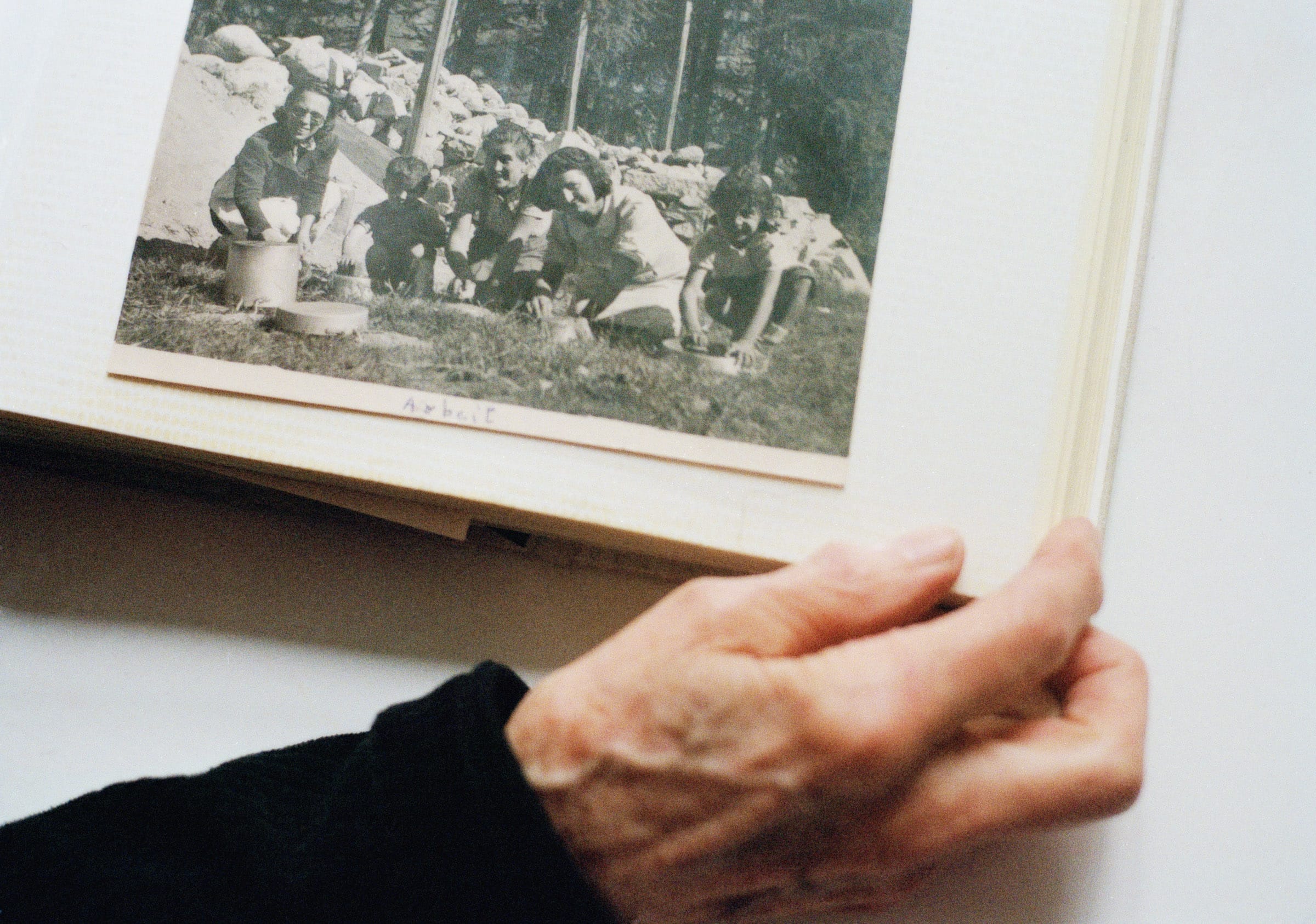

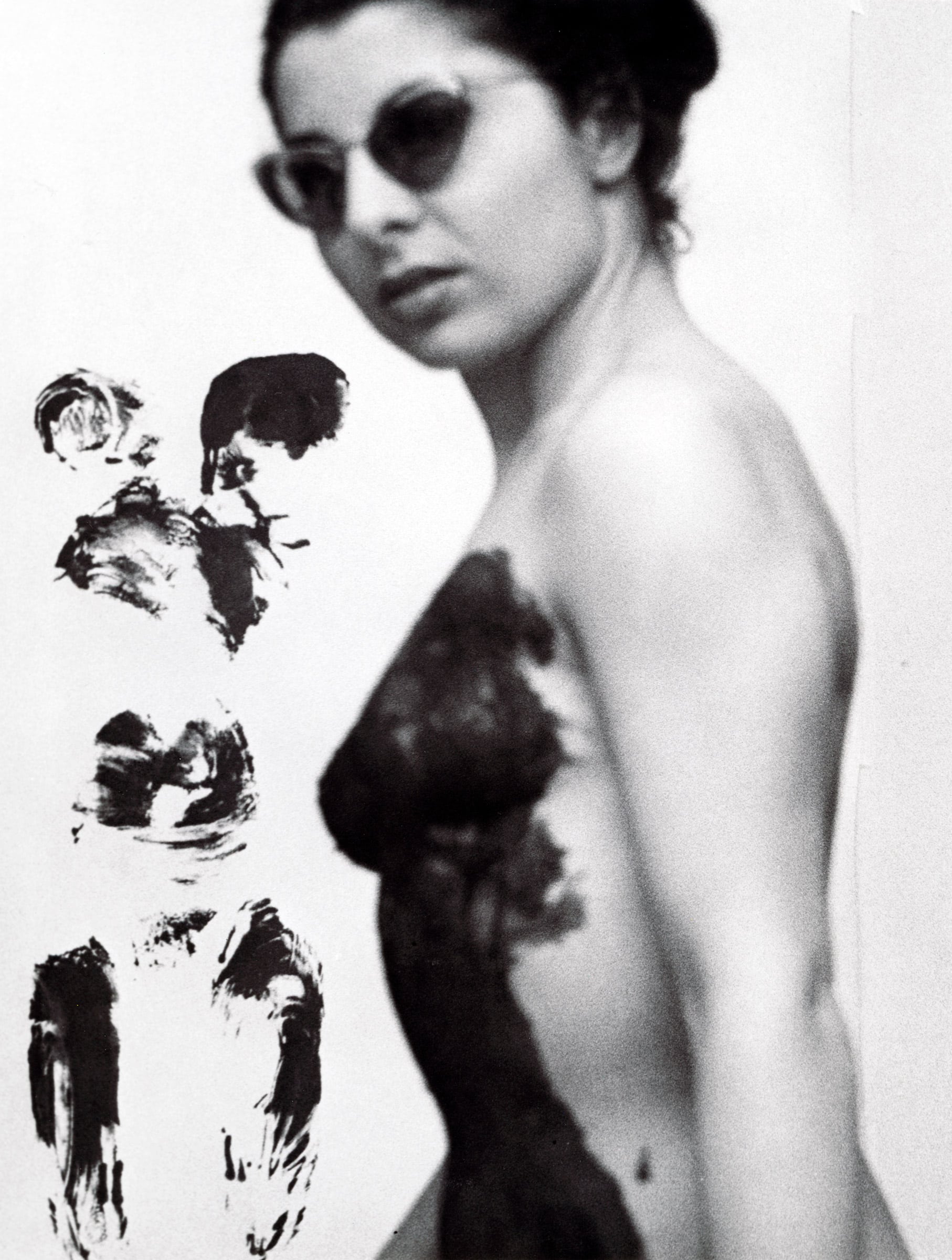

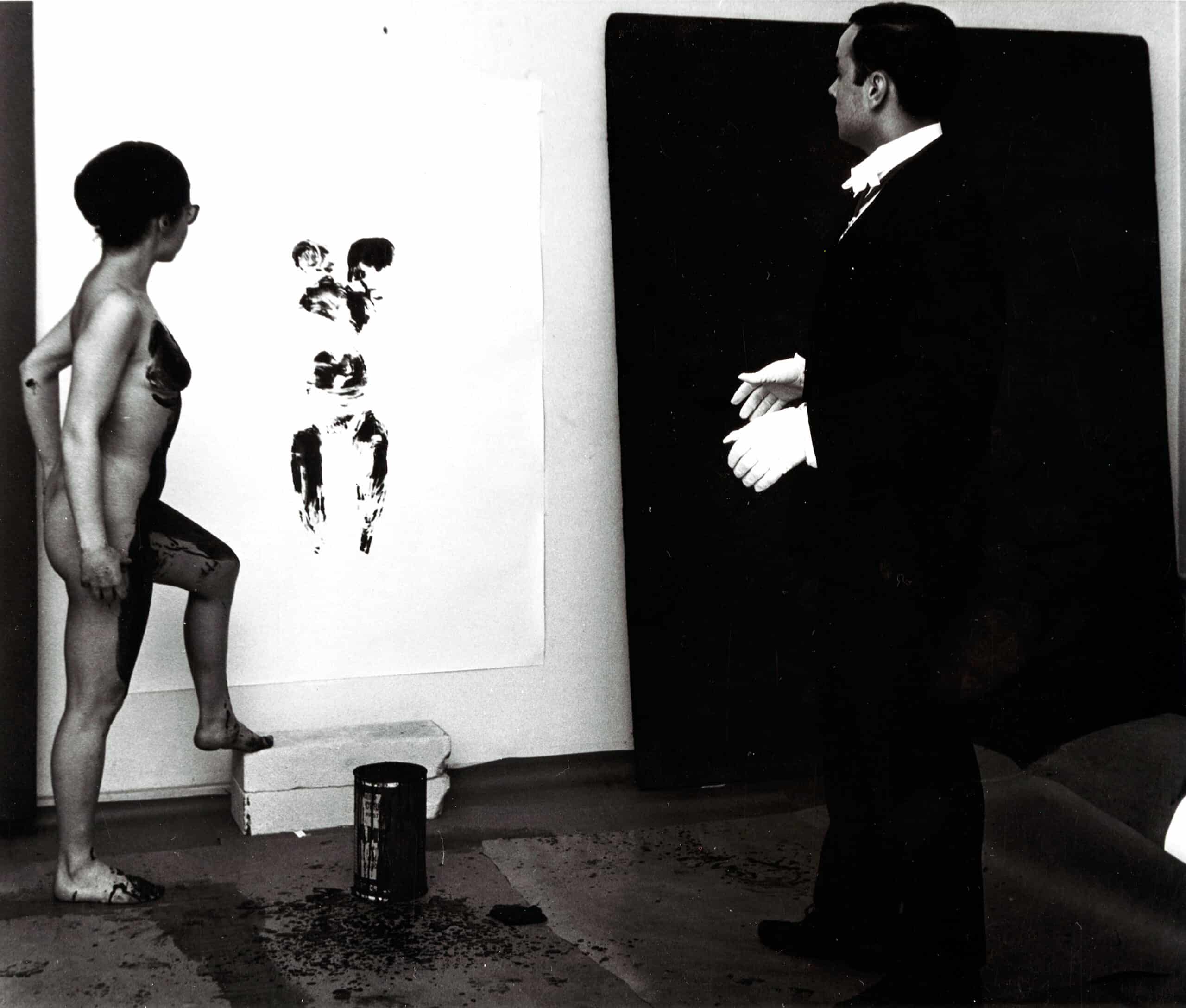

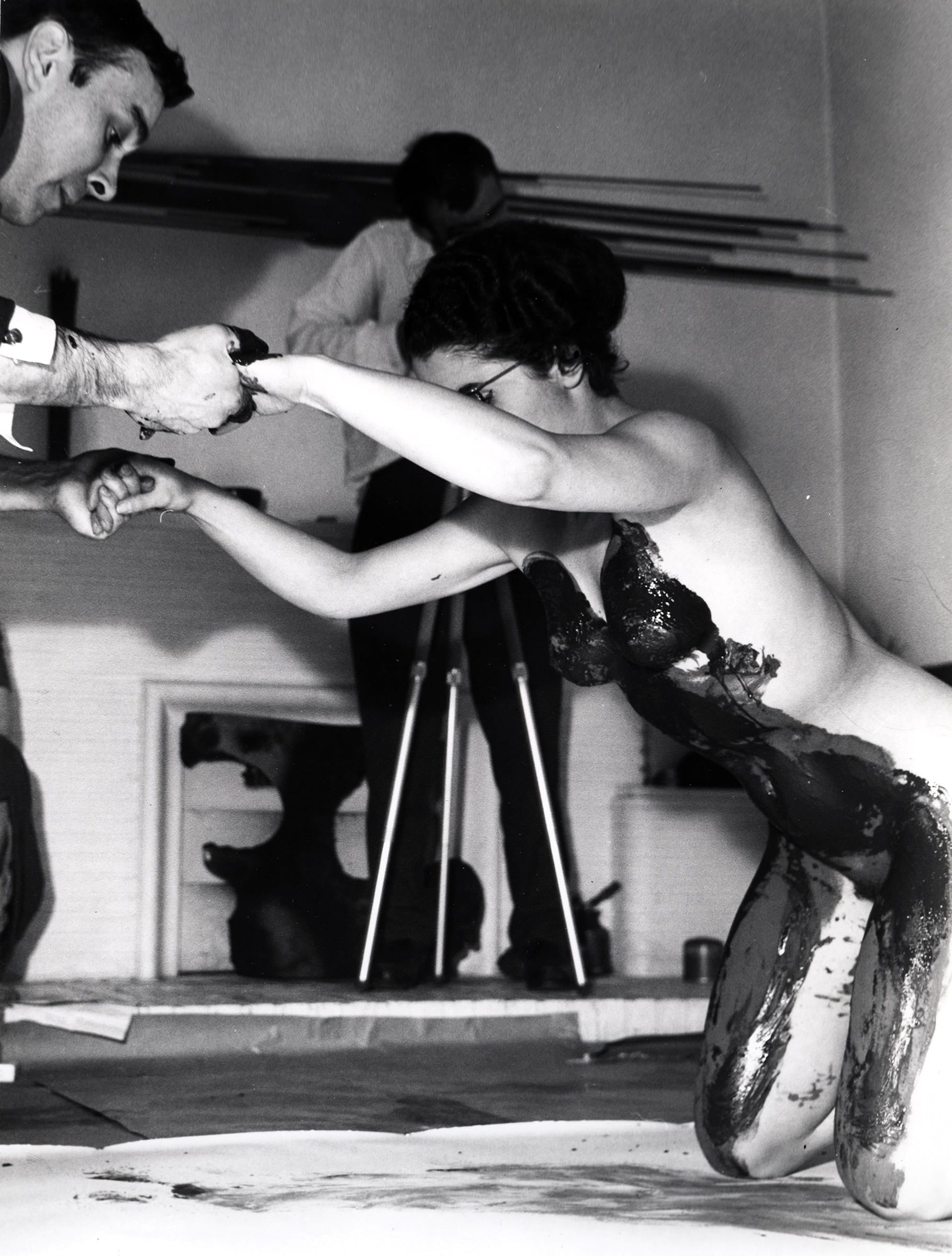

Elena Palumbo-Mosca is one of the enigmatic naked blue bodies that painted Yves Klein’s canvases at the Galerie Rive Droite, Paris, in 1960 for the making of the revolutionary Anthropométries series. Now 87, Turin-born Elena has lived a rich and fascinating life, drawing on her astute skills of observation to interpret the ideas of those she’s found herself close to. Elena first encountered Yves while working in Nice as an au pair for the artist couple Arman and Éliane Radigue (a painter and a musique concrète composer respectively), and after receiving a classical education in the mountains of Mont Blanc and training as a professional diver, she shared with him a love of discipline combined with movement—Klein himself became a master of judo at age 25. Fluent in Italian, French, English, and Spanish, Elena has worked as a political interpreter for over 30 years, and more recently has translated poetry by her friend Ángeles Mora. She has a love for language and communication that extends further than words.

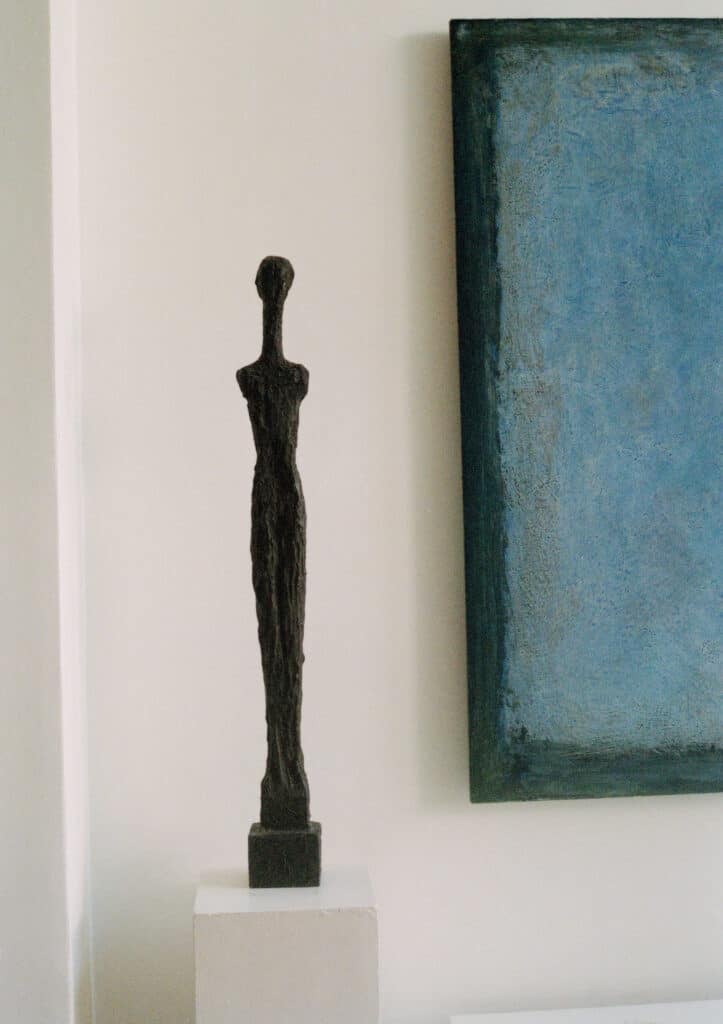

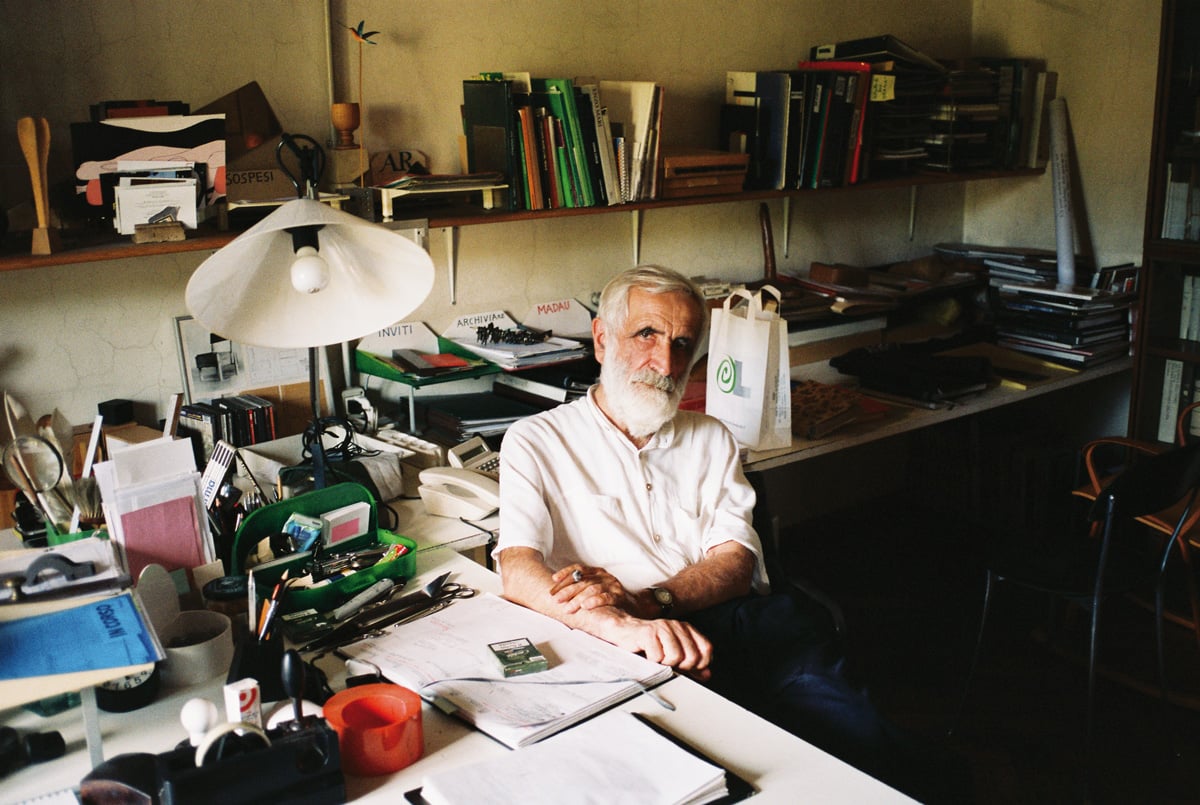

Elena makes for enhancing company, as I come to find out over the course of our interview. We begin in her elegant blue town house in the northern part of Brussels, where, between graceful sculptures that she posed for, she cooks me an omelette with oil ground from her olive trees in Italy. We talk about her life, of a kind of pre-war Paris at the Hôtel La Louisiane with Miles Davis and the Black Panthers, and her work and friendship with Klein. Refuting the ‘human paintbrush’ term usually ascribed to her, Elena explains the collaborative nature of the works, the precision necessary to execute the performance. Based on their own respective training, the two had a desire to leap into ‘the void’, a concept central to Yves’ work. His was a prolific and short career that stormed the European art scene before his untimely death at the age of 34, and a revolutionary practice that aimed to translate the artwork of ‘feeling’ by using natural elements, like fire, water, and the human body, as mediums to trace the communication between the artist and the world. At the end of our lunch, Elena invites me into her walled garden where she keeps the camembert, surrounded by English roses in full bloom. Noticing me, she asks if she can teach me something, telling me that I must absolutely correct my posture and focus on alignment, and that she can give me lessons. One month later, I decide to take her up on the offer and spend a transformative few days in the beautiful ruin that she reconstructed with her hands in front of the sea and olive groves, strengthening my spine in more ways than one.

close

close