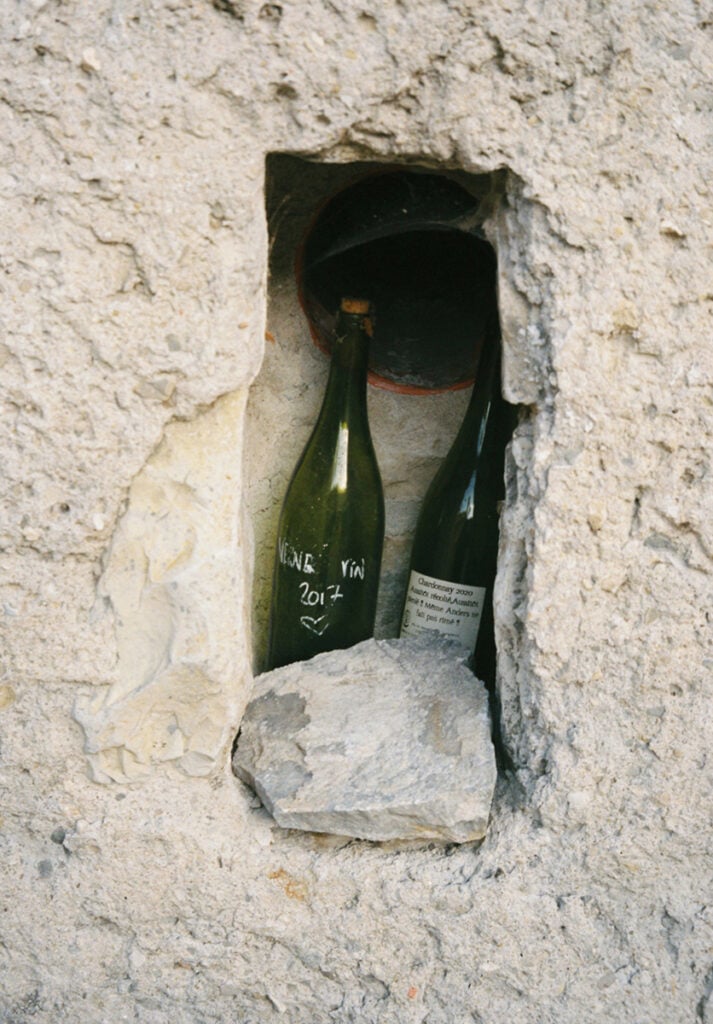

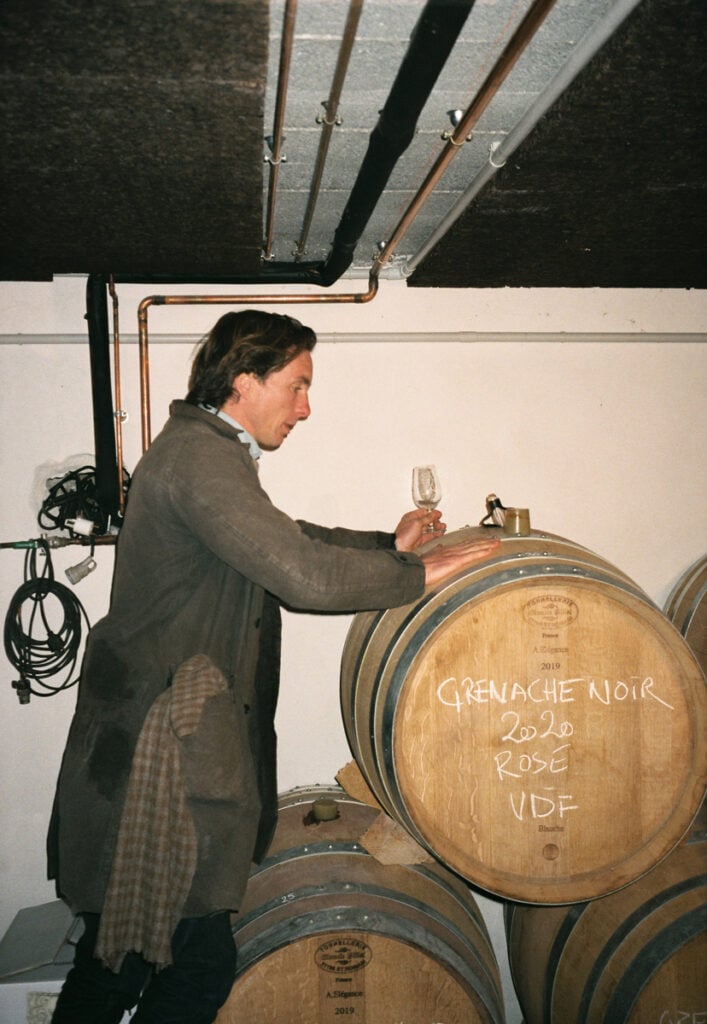

Our last morning in Valvignères, Anders dropped us a pin; it was a while after they’d got there already, but at the time we were still schlepping around the breakfast table. Business and pleasure were starting to blur. We threw our bags in the car and eventually located the ranks of Ardèche natural winemakers working their way through the vines; the sun high above, they armed us with secateurs and gave us a crash course in pruning that doubled as entertainment for the old hands. That day was a show of solidarity for two winegrowers who’d started the conversion to organic, much to the ire of locally established non-organic producers, and by this stage we were about ready to throw in everything and swell their ranks indefinitely. In 2016, Anders Frederik Steen and Anne Bruun Blauert made that move, leaving their native Denmark to continue the winemaking started here by Anders in 2013. At that stage, he was better known as cofounder and sommelier of two Copenhagen institutions, Relæ and Manfreds, which garnered equal parts praise and criticism when they first opened for pushing a new kind of ultra-seasonal, organic cuisine paired only with natural wines. Their impact on Nordic fine dining is now talked about in the same breath as that of Noma—where Anders also trained as an apprentice sommelier. Anne, meanwhile, built her career as a social worker in prisons and caring for victims of sexual assault, but after the move became fully implicated in the winemaking. Every year they all but start from scratch, never repeating the same cuvée twice, but varying their presses or macerations or the blend of grapes, depending on the fruit itself. And it works; the bottles sell out before they’re even released. Unlike these city kids with idle fantasies of bucolic life, the couple have put in the hard yards and it shows, their wines carrying fistfuls of complexity and whatever quality it is that makes your head hang low, nose in the glass, in a form of visceral entrapment. As much wine as I might like to consume though, the real reason we came is the stack of Anders’ notes that arrived on my desk a few months ago, around 200 pages of recopied diary entries, scraps of reflections dating back to 2013 and that first foray into winemaking, the whole process as it unfurled, with all the doubts and wrong turns, appraisals of other wines and eventually their own, of the work of a sommelier, and eventually the new ruminations of those who’ve reached the top of their game and are looking for the next mountain. For the three days we visited, the wine and conversation flowed—about the book we’ll be making from the notes and everything in-between.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

close

close