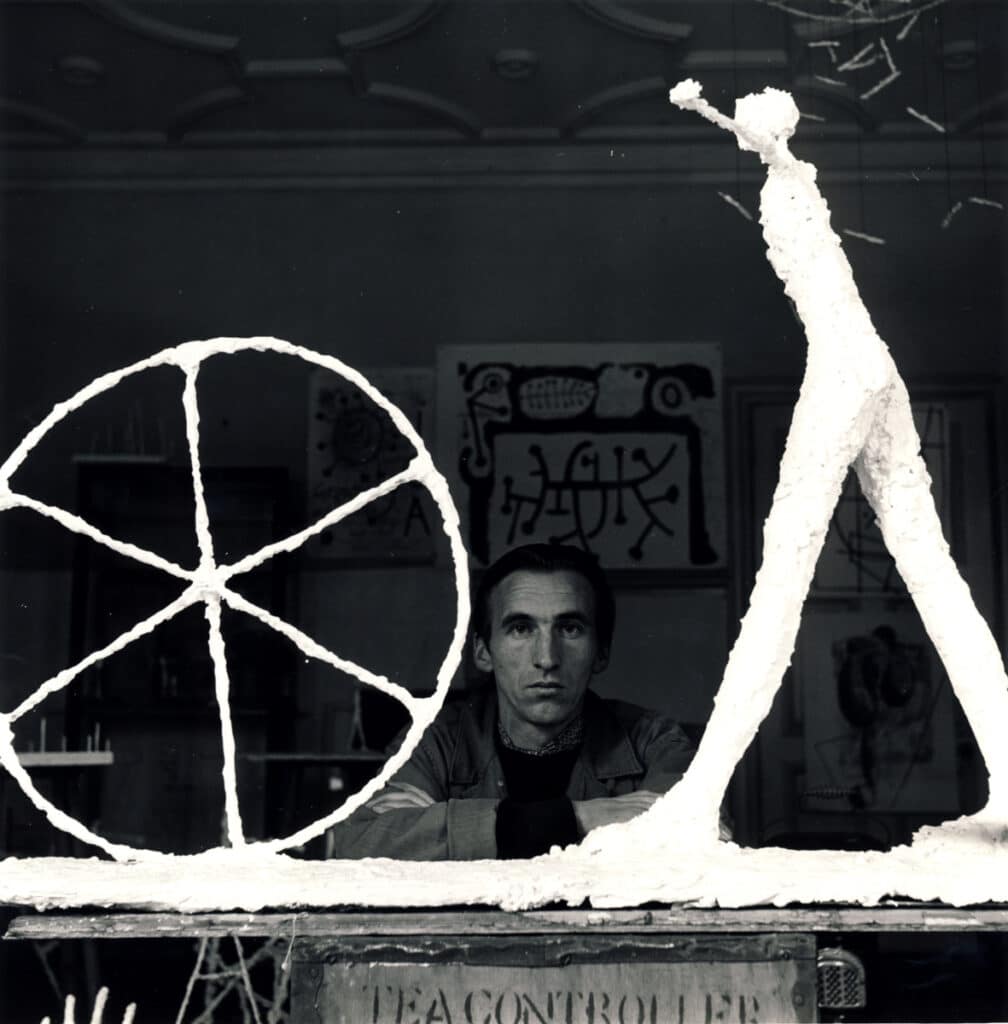

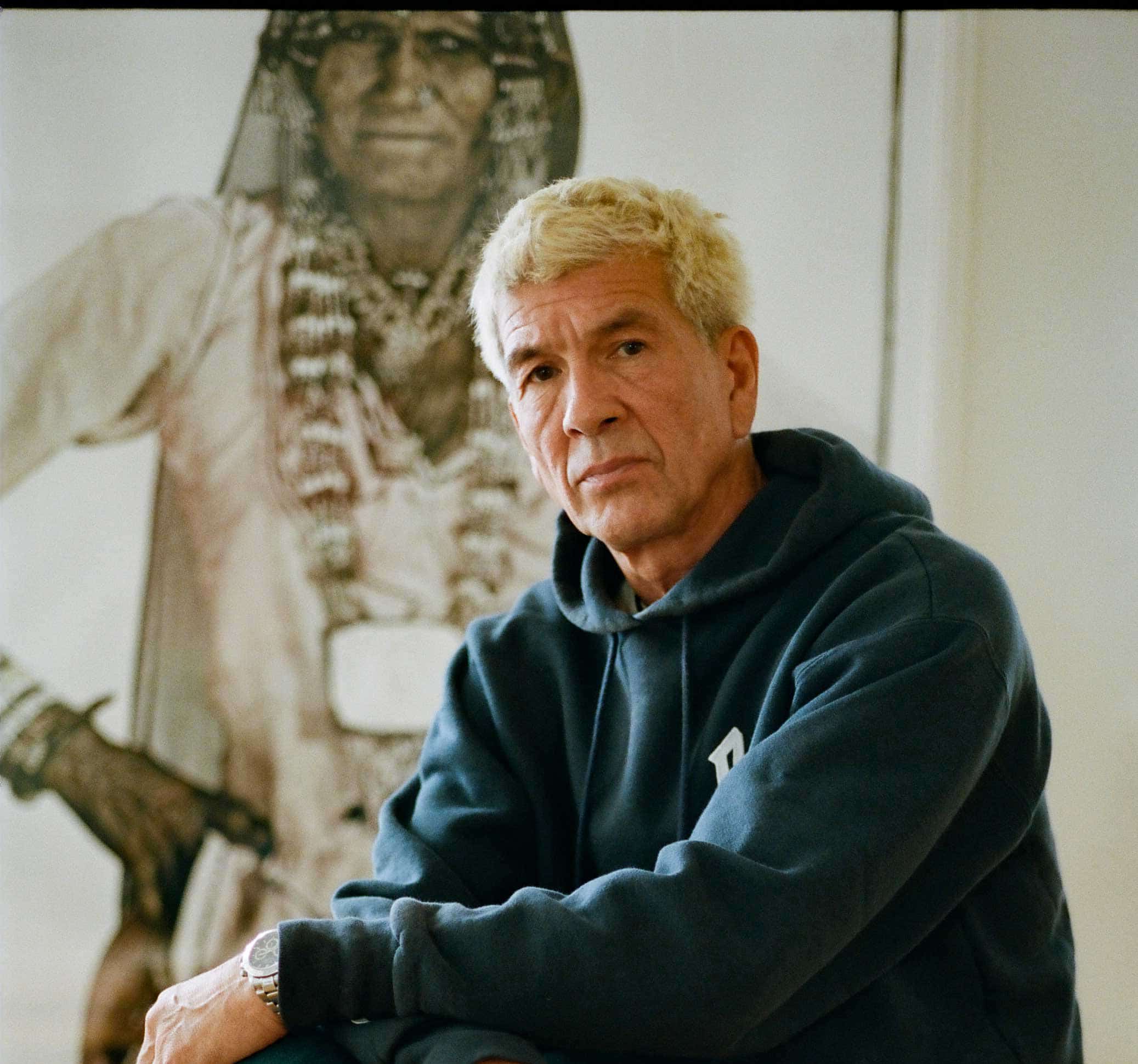

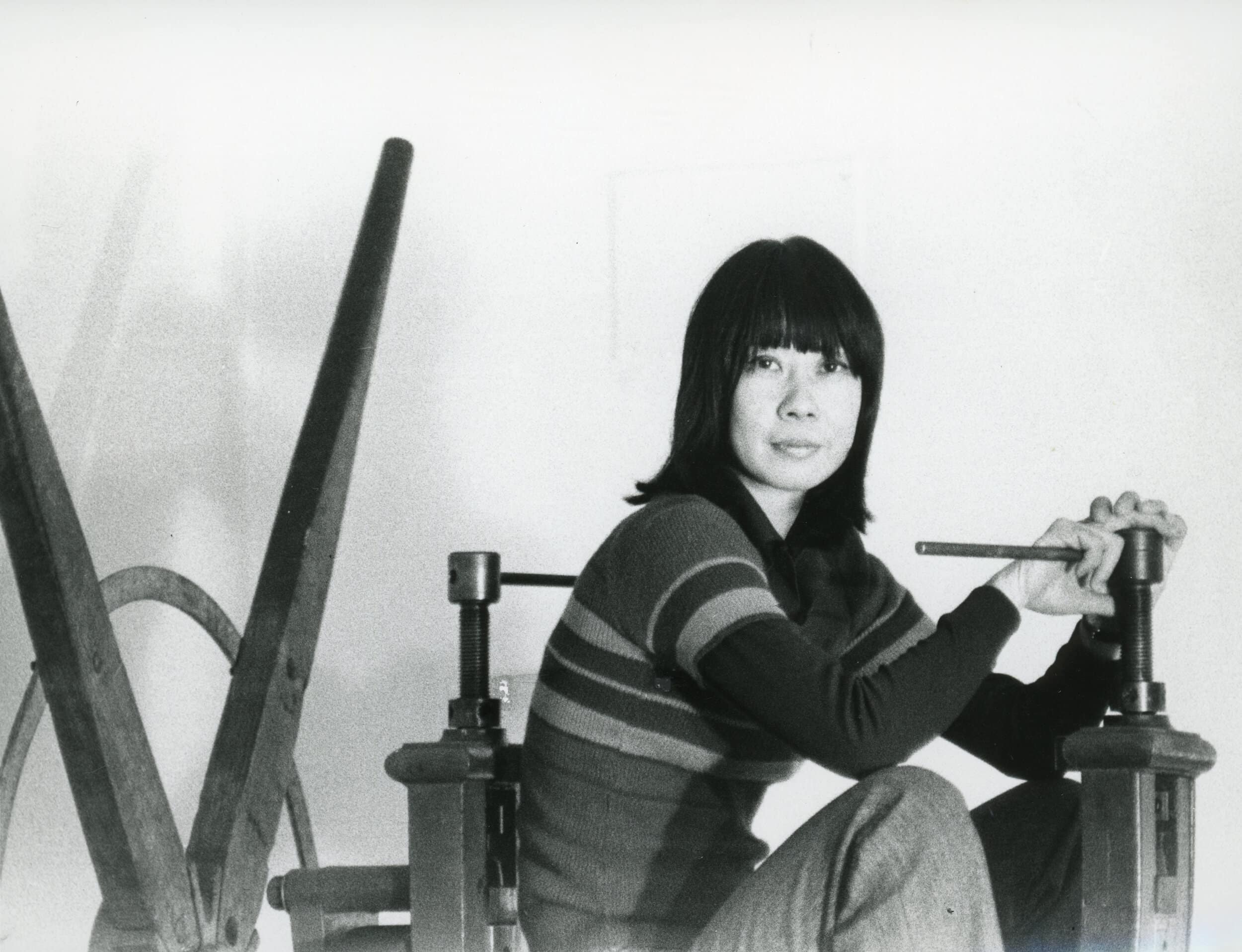

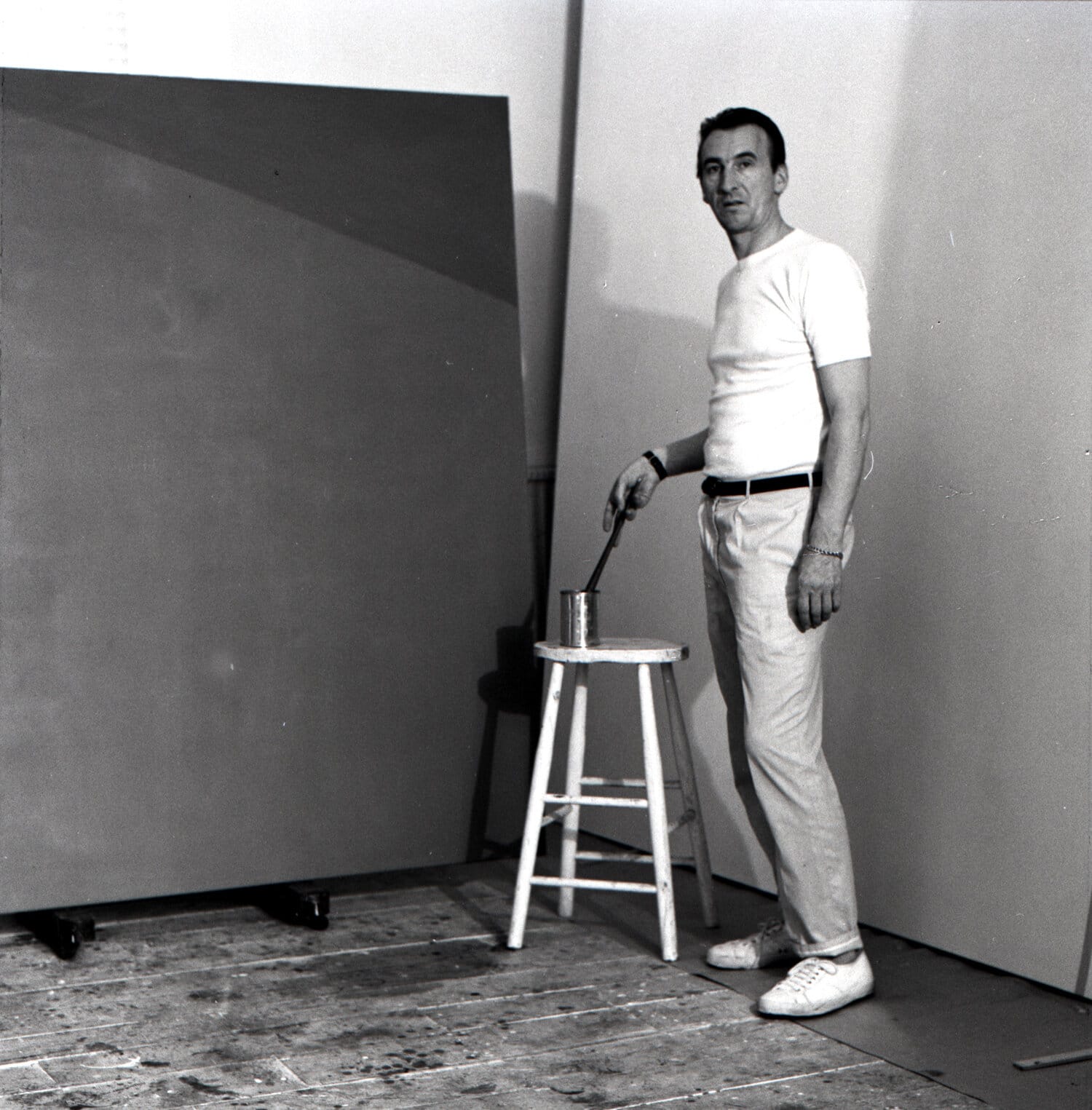

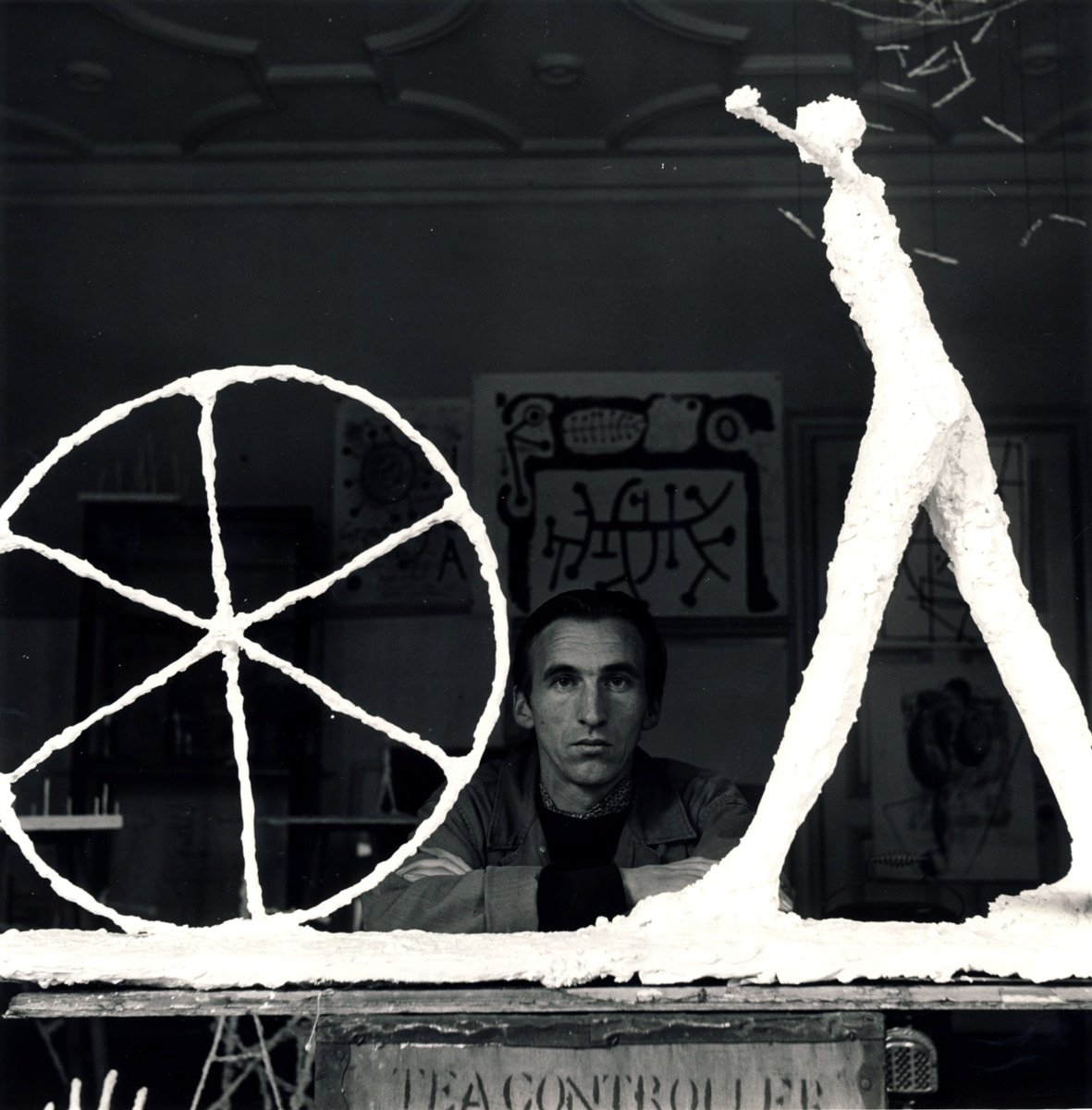

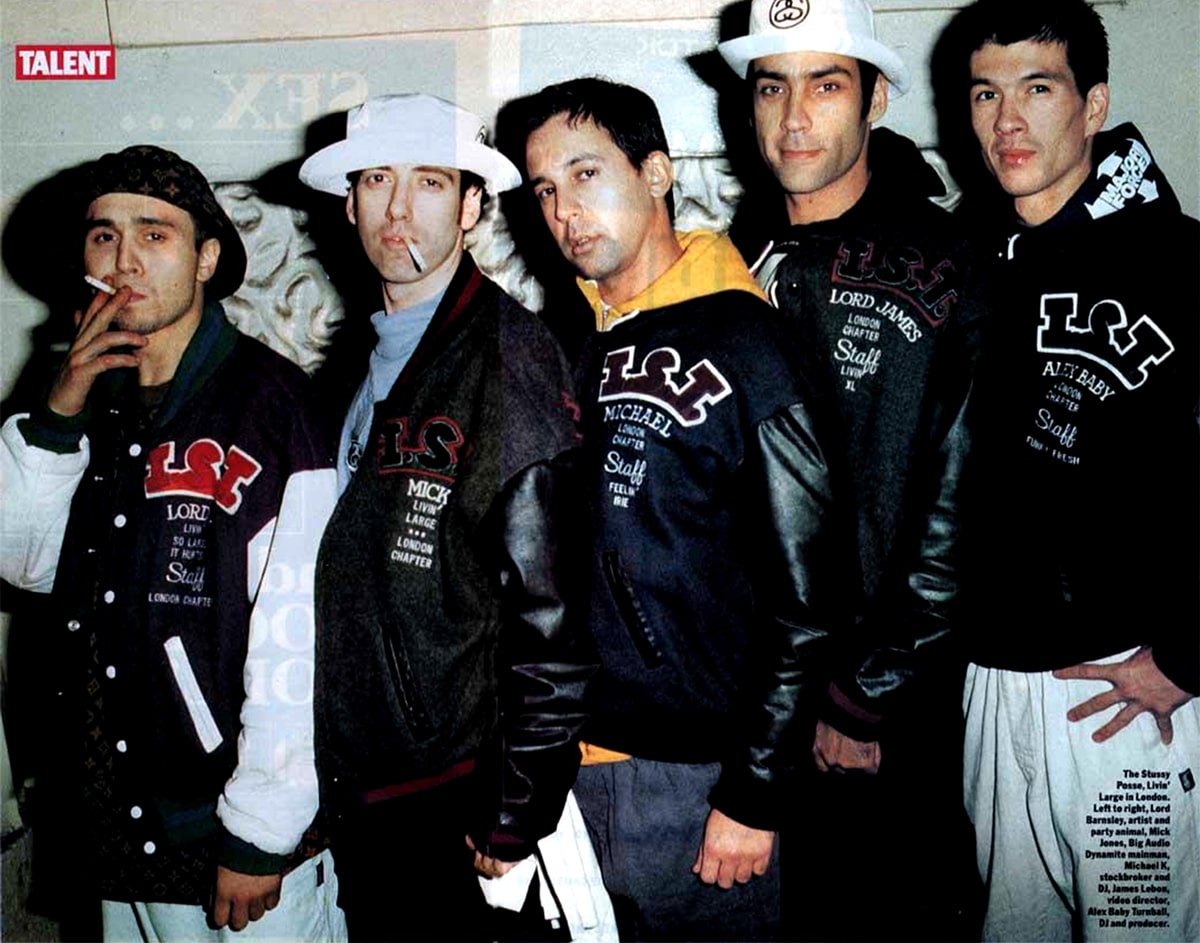

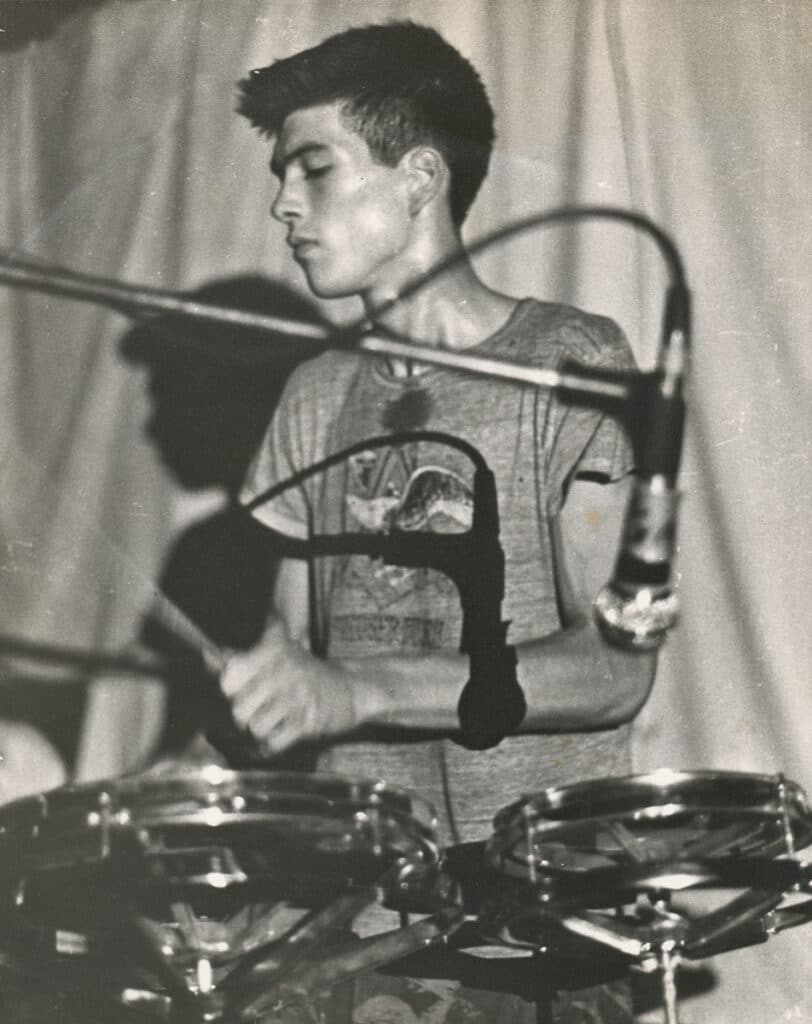

London: Alex Turnbull has been immersed in art and experimental culture all his life. As the son of William Turnbull and Kim Lim, the multi-hyphenate musician, filmmaker, skater, and original member of the International Stüssy Tribe was born to two of Britain’s greatest post-war artists and sculptors. As well as pursuing a cross-disciplinary artistic life of his own, Alex has managed his parents’ estate with brother Johnny since 2006, repositioning William Turnbull and Kim Lim as key figures in international modern art.

Entering Alex’s North London home is like stepping into a microcosm of his creativity. On the parquet flooring of his kitchen—in front of a print made by the street artist Haze for the Mo Wax record label in association with Gimme 5—is one of William Turnbull’s bronze Blade sculptures. Nearby, a limited edition RVCA skateboard from artist Eric Haze signed ‘For Alex!’ rests next to an illustration by Kim Lim, whose abstract yet organic wooden and stone sculptures are scattered throughout Alex’s inviting home. Noticing a black-and-white photograph of Kim Lim in her studio in the ‘60s beside a resin sculpture produced by Supreme, it’s clear how much of Alex’s expansive aesthetic is a product of his parents’ boundless art.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

close

close