The residence of Eva and Ján Mathé is a rare sighting in the Slovak city of Košice. Its smooth white walls and slender window frames of pine wood strike a delicate balance and respect modernist principles. The house stands out against a blend of gothic domes, baroque palaces of the Hungarian nobility, and socialist residential towers left over from the city’s industrial surge in the second half of the 20th century.

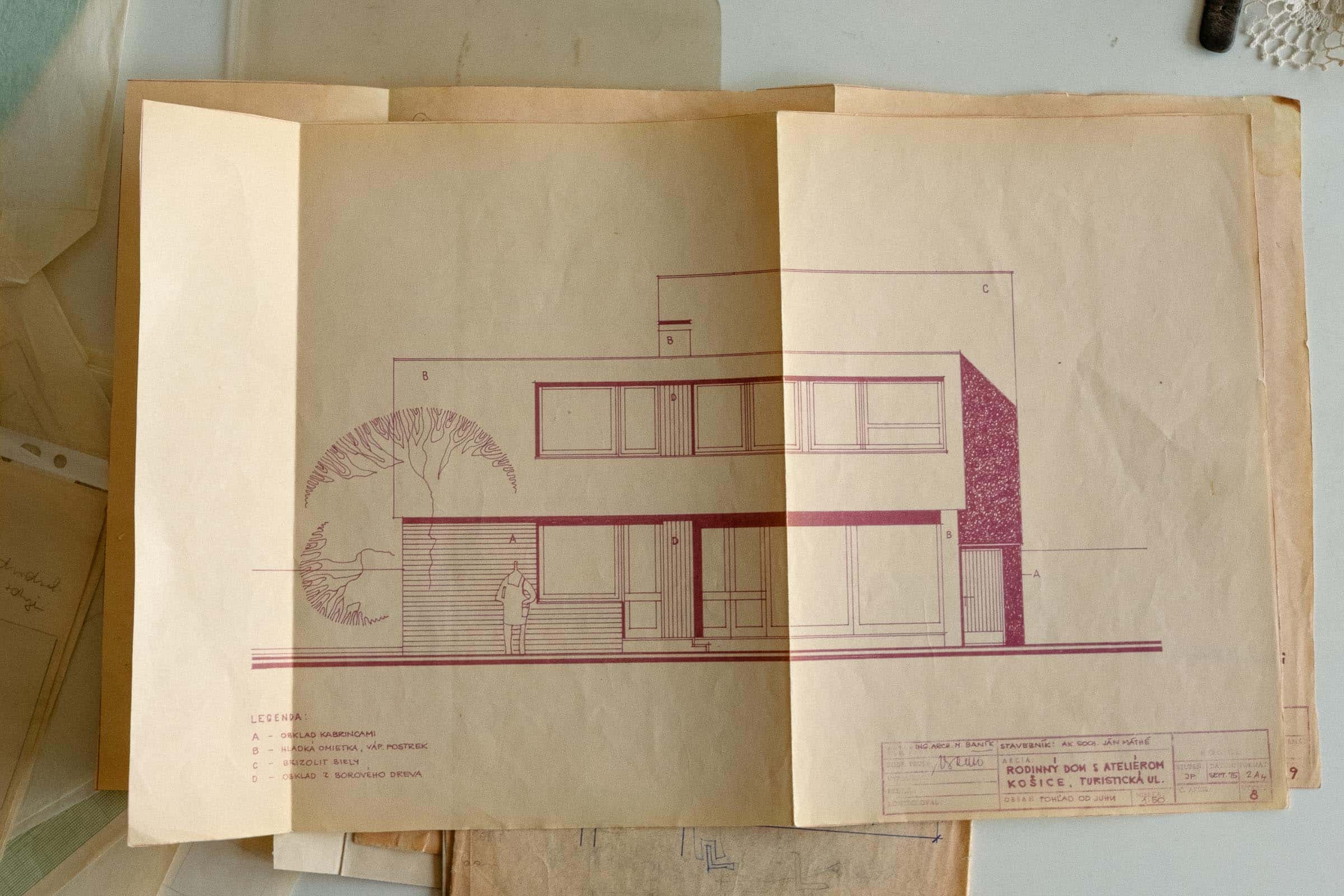

The Communist Party then controlled all aspects of urban construction and swiftly erected many uniform buildings. Few architects managed to let their individual style shine through in these large public commissions. Most single-family dwellings were based on a standardised design devised by the state. Privately owned villas virtually disappeared. And so the Mathés’ home, which was completed in 1983, is not only a testament to the owners’ impeccable taste but also to their admirable resourcefulness and courage.

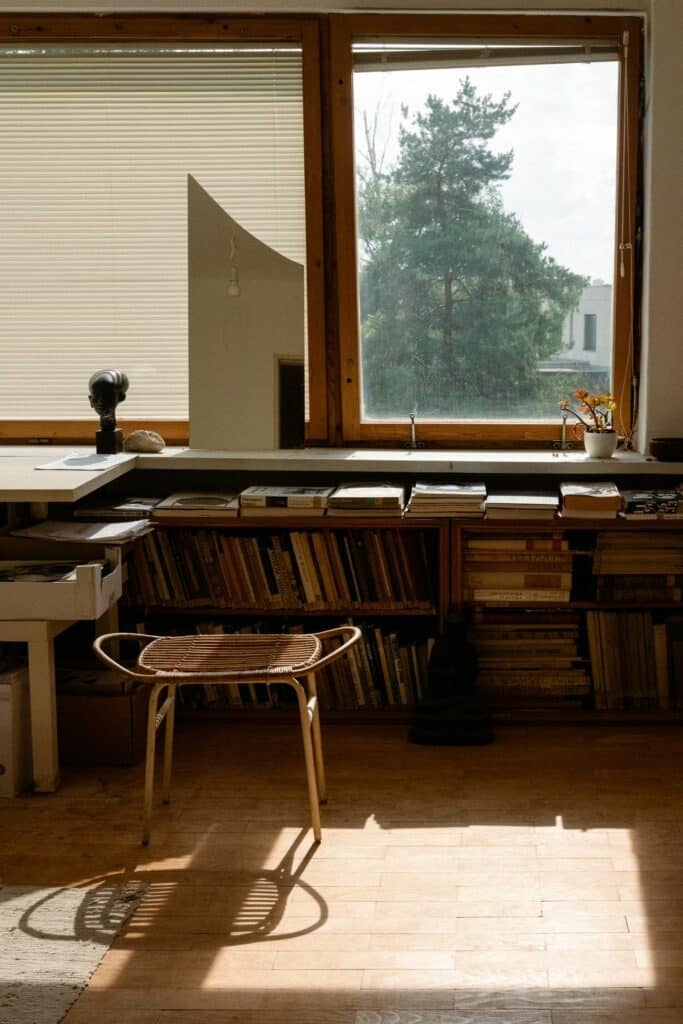

The couple—sculptor Ján and paediatrician Eva—were invested in the design of the house. You can see echoes of Eva’s travels to medical symposia around the world; she was particularly dazzled by Alvar Aalto’s Finlandia Hall in Helsinki, evident in the villa’s simple layout. An open living area with a fireplace spills into the garden on the ground floor, with bedrooms plus a study upstairs. At mid-level, a generously sized sculpture studio is bathed in soft light.

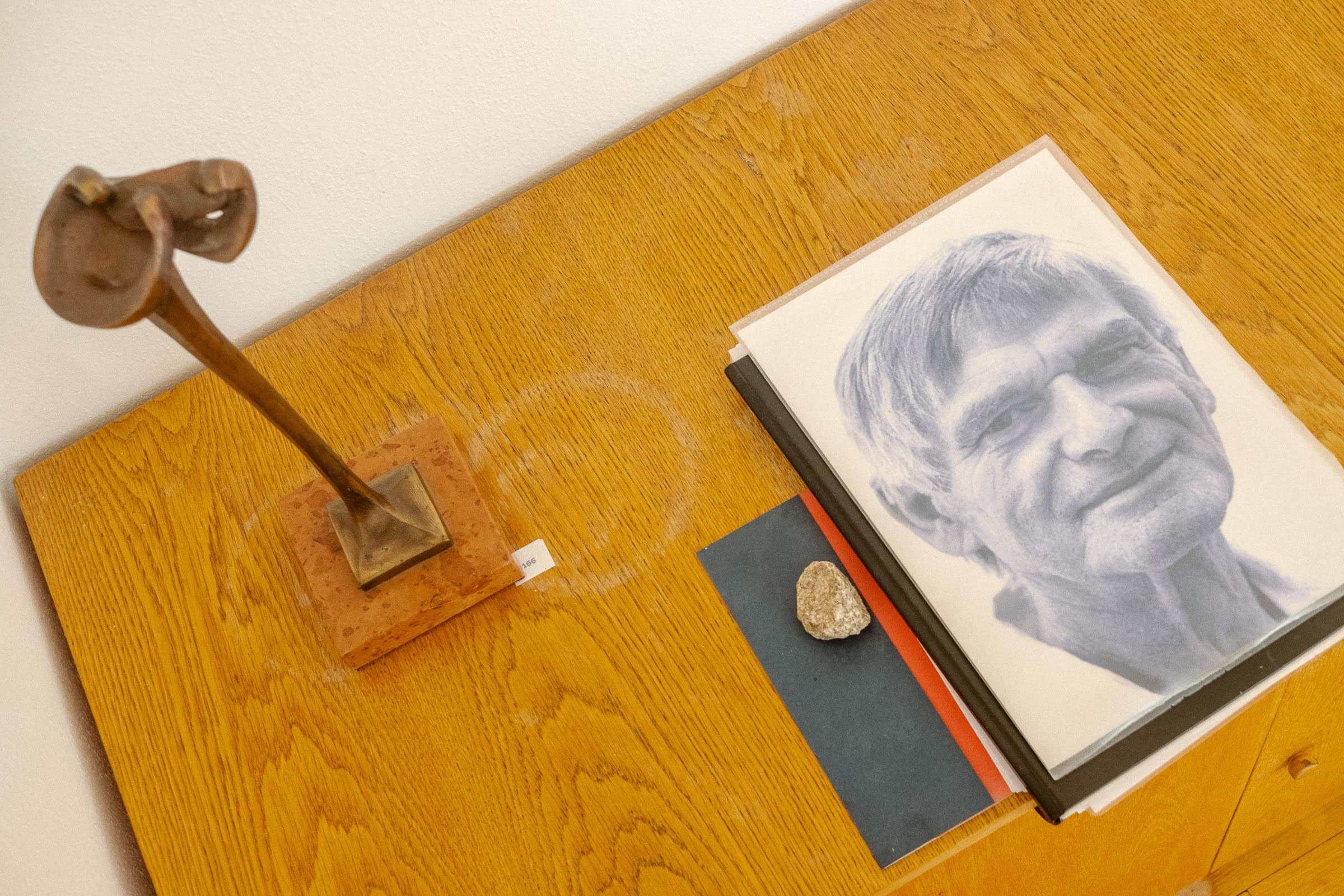

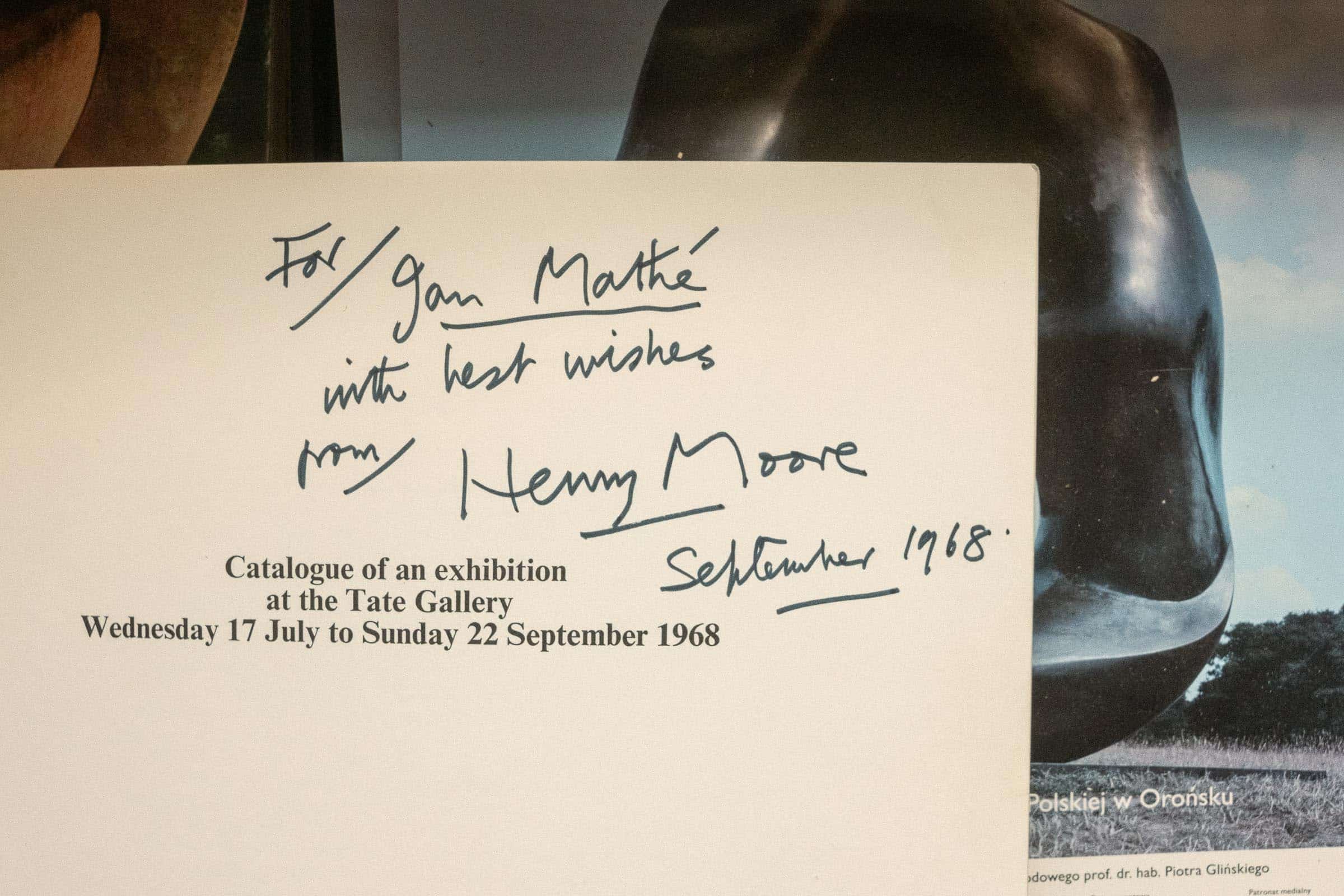

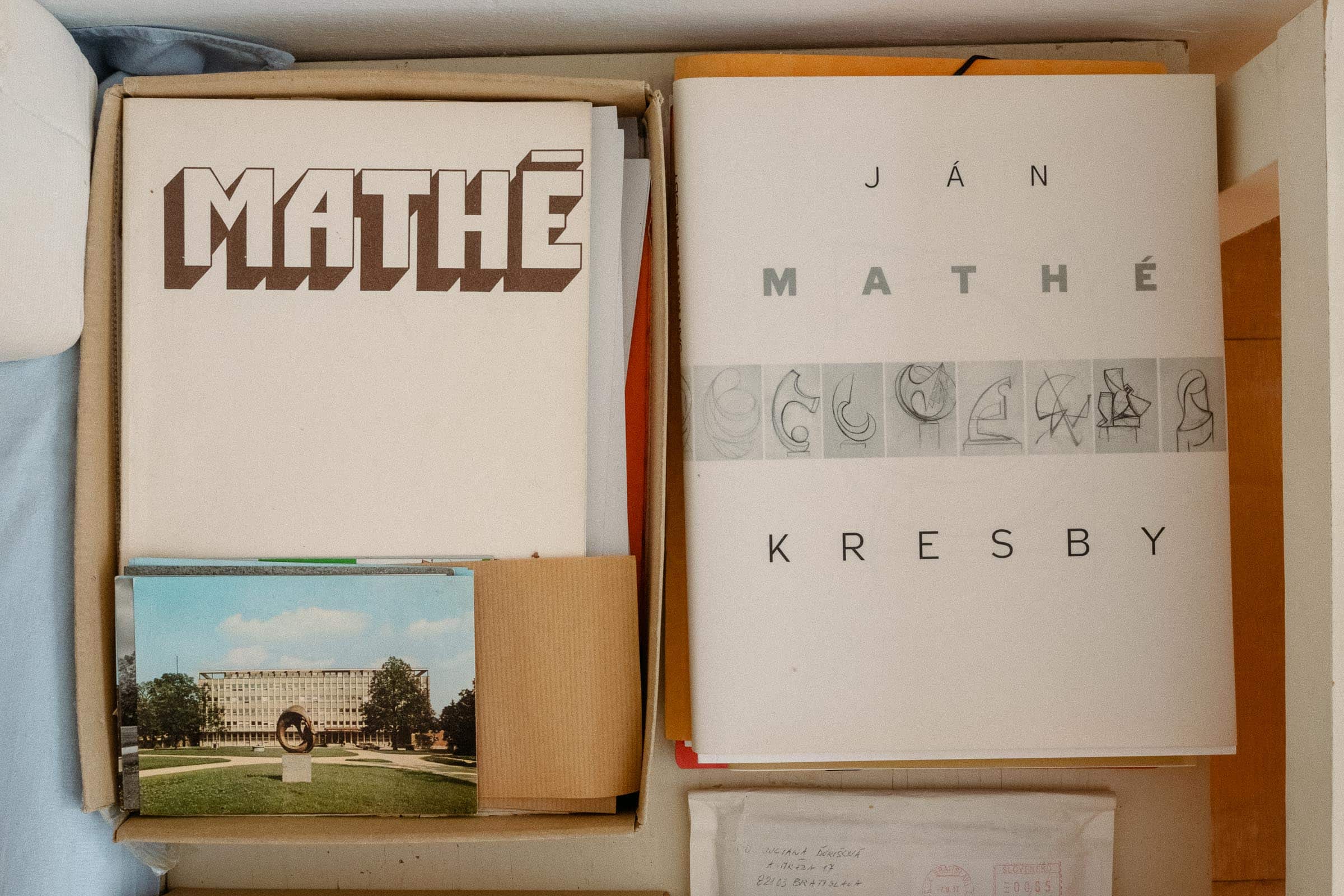

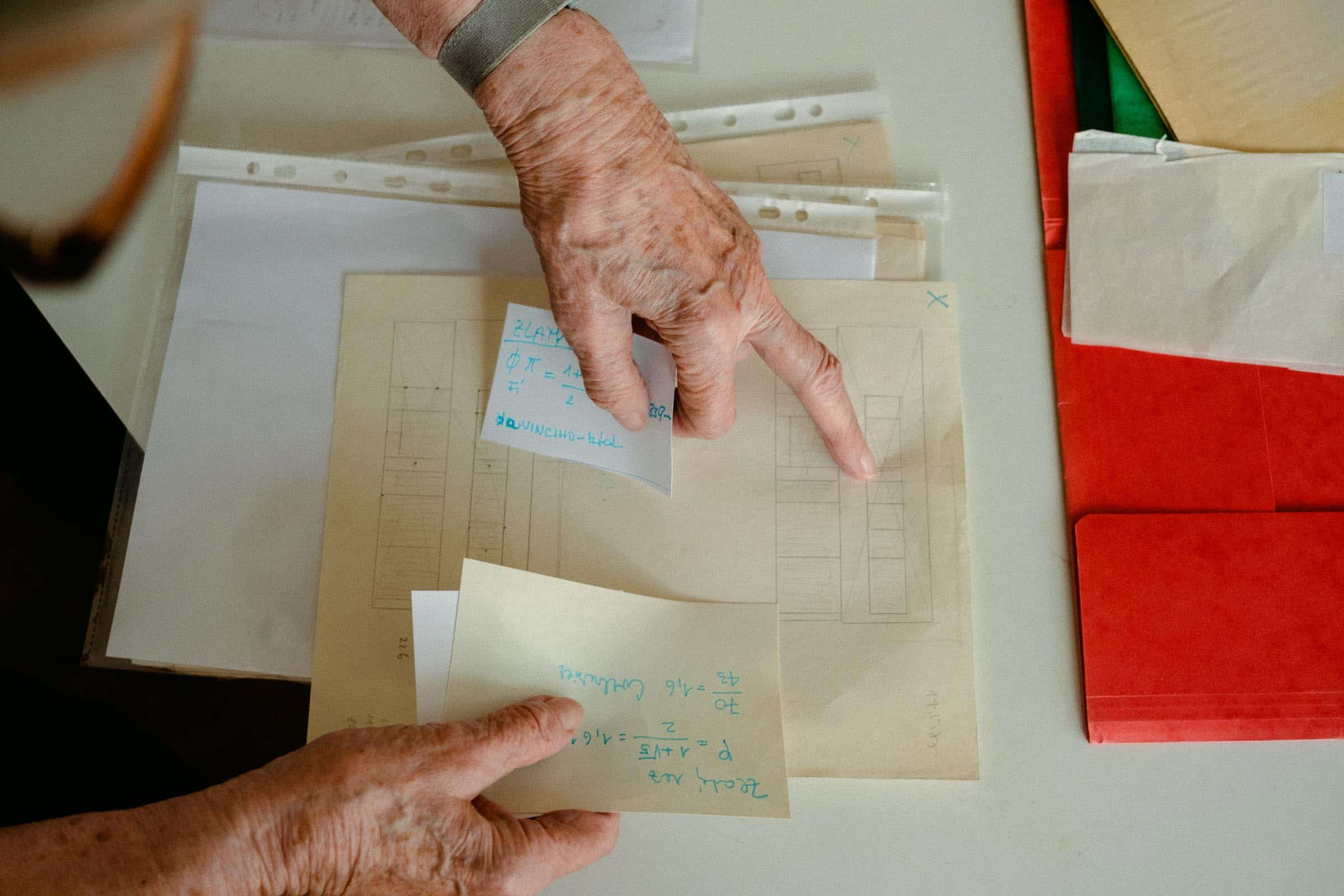

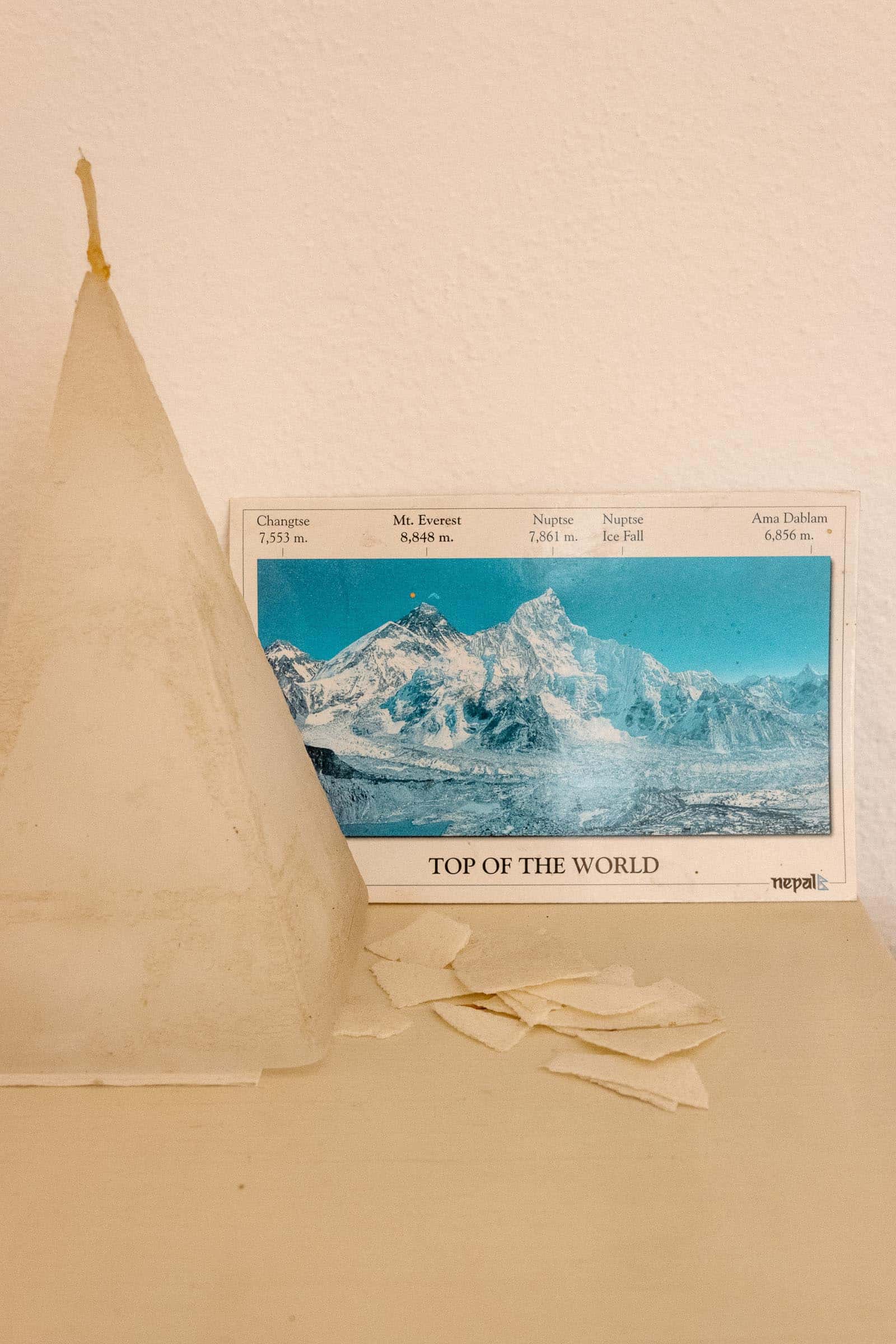

The atelier has not been in use since Ján died in 2012, and it’s a trove of the sculptor’s work, spanning models in clay and plaster with bronze casts, as well as wood and stone carvings. The human body had preoccupied Ján since early in his career and increasingly took on an abstract form in his work. His pieces express movement and human relationships in fluid gestures. They are reminiscent of those by the British sculptor Henry Moore or Constantin Brâncuși from nearby Romania.

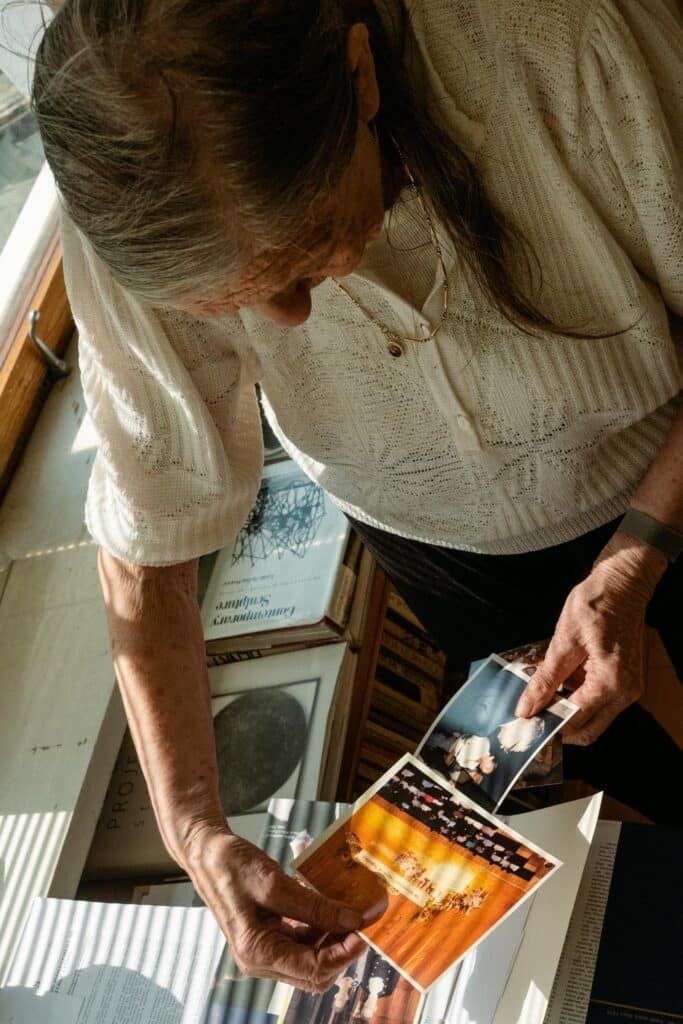

Eva, now aged 91, is set on preserving the house as well as the collection of Ján’s artworks. In 2019, the building was designated Slovak cultural heritage. Eva has recently donated it to the city of Košice, which will open the space to the public as a museum when it no longer serves as a home. For now, Eva’s dumbbells under the washbasin in her bathroom are as much part of the place as the hammer and chisel tucked away in the drawer of Ján’s studio.

close

close