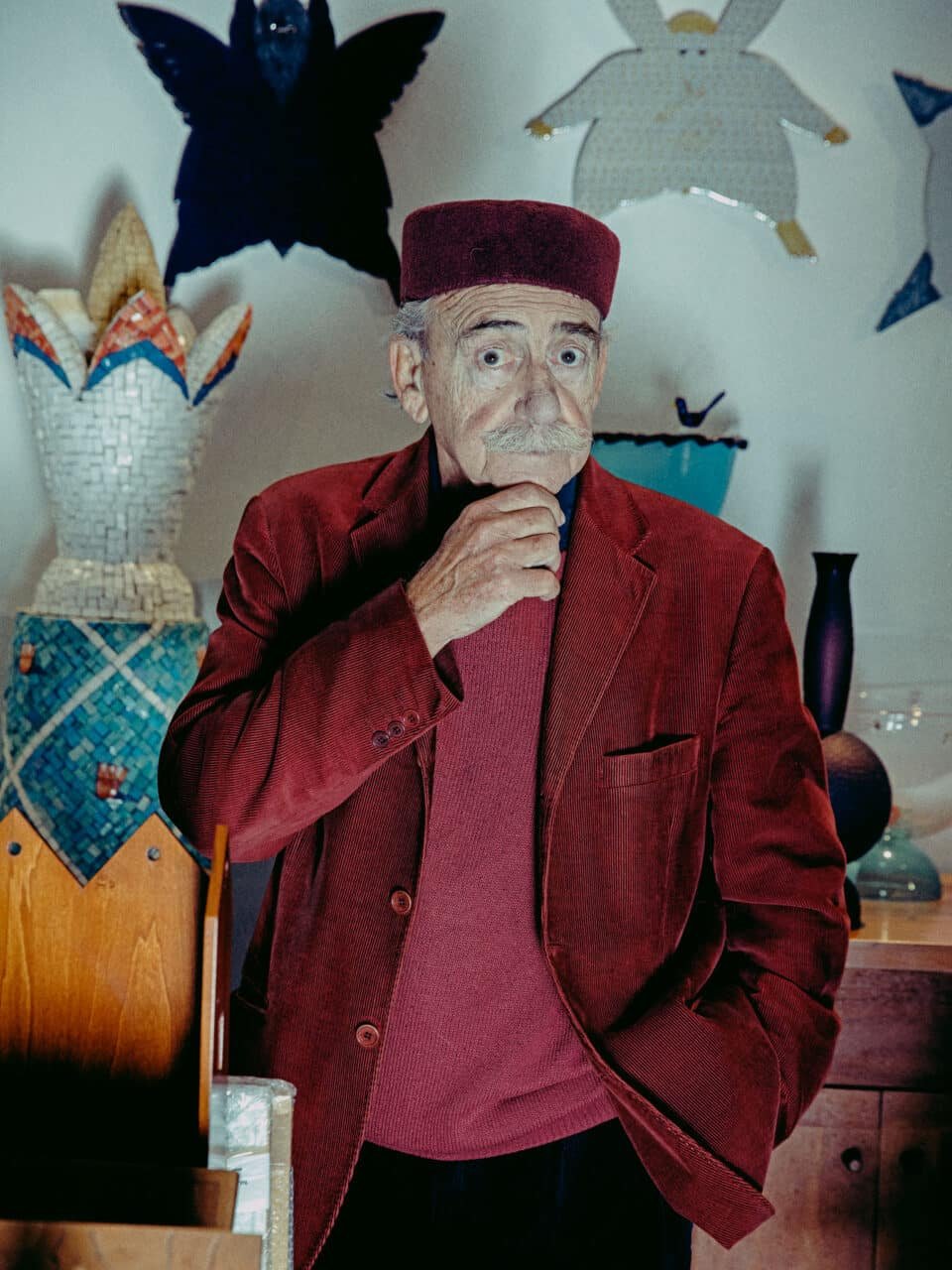

The Italian designer Ugo La Pietra is featured in issue #30 of Apartamento magazine.

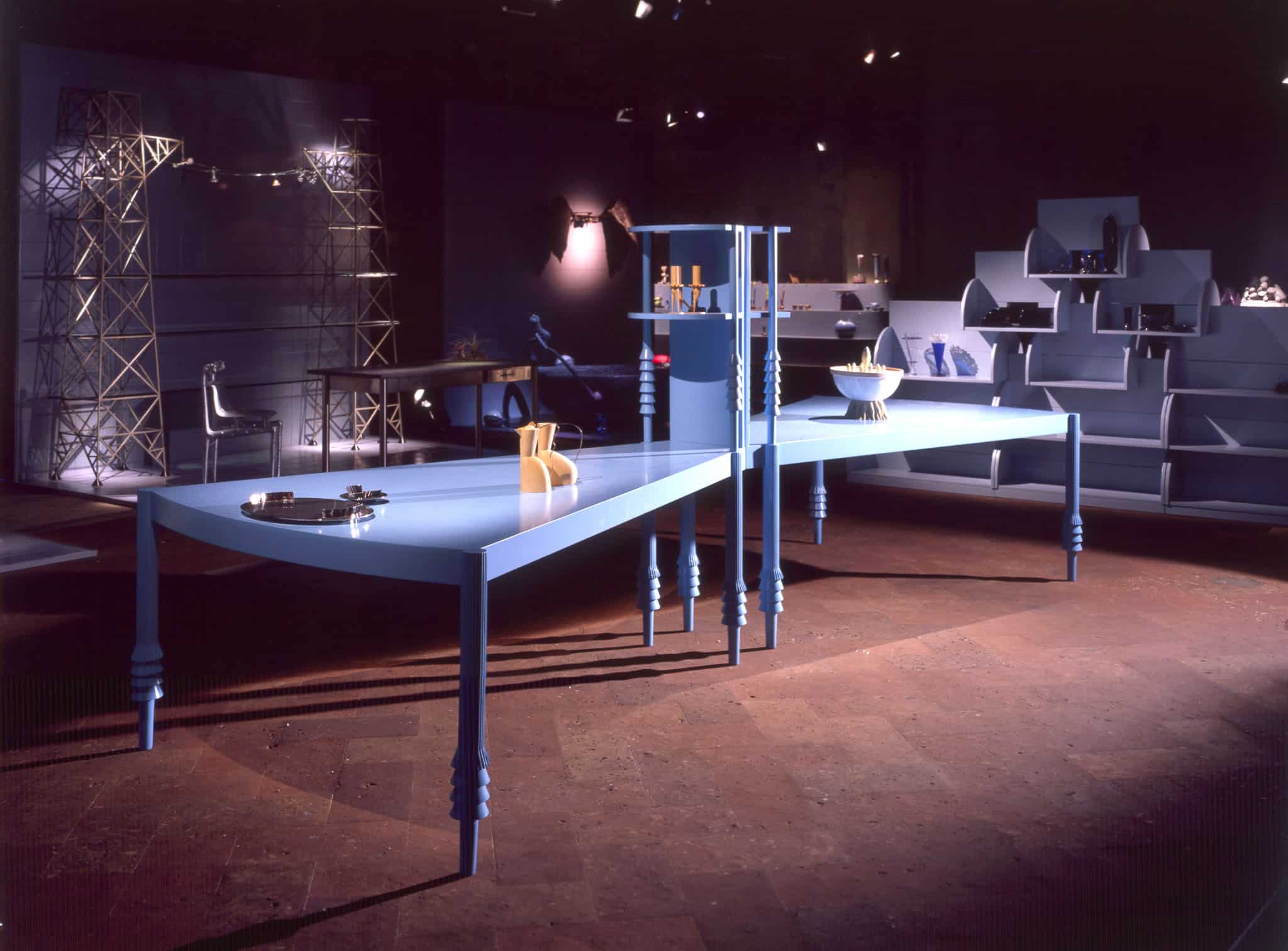

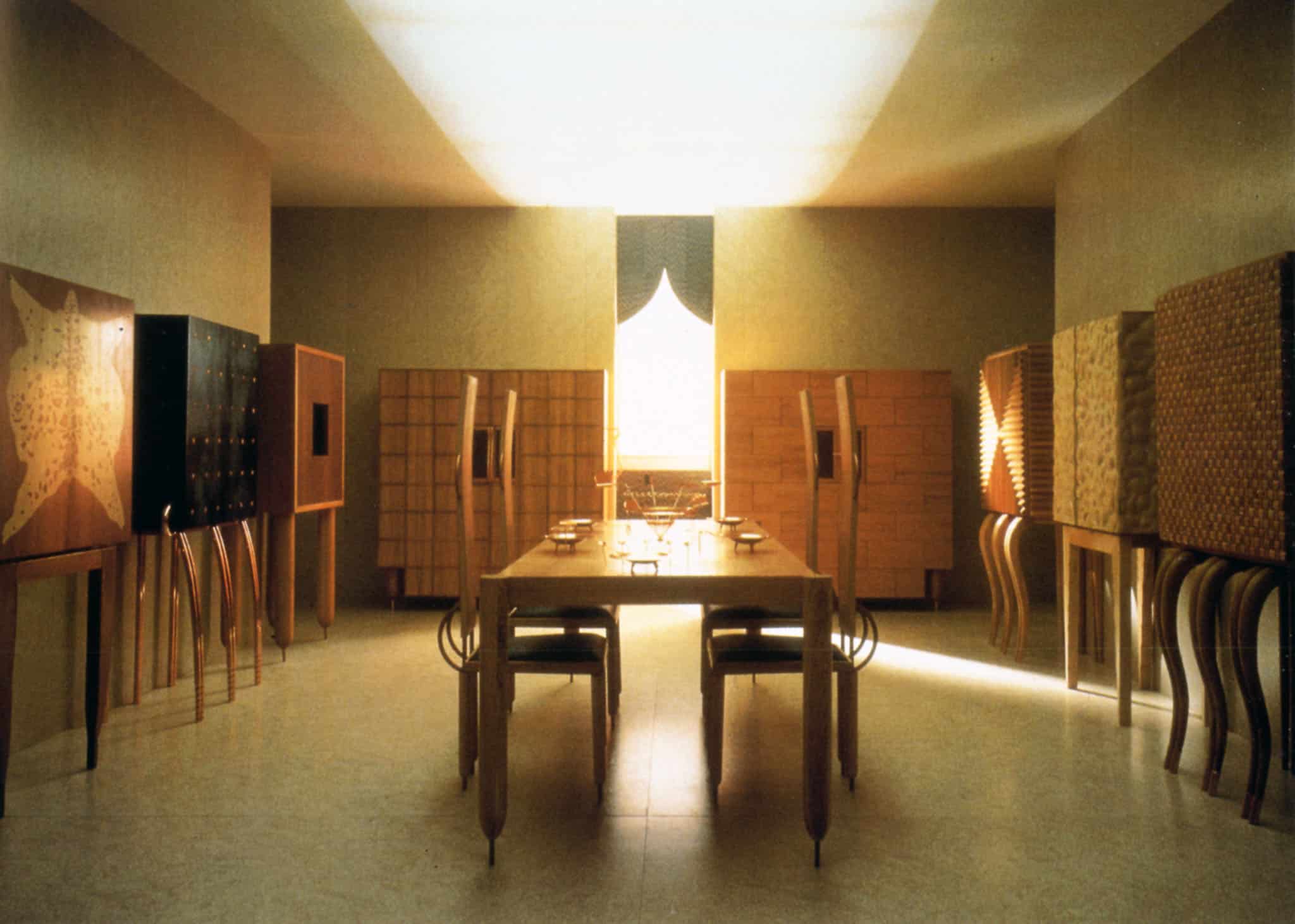

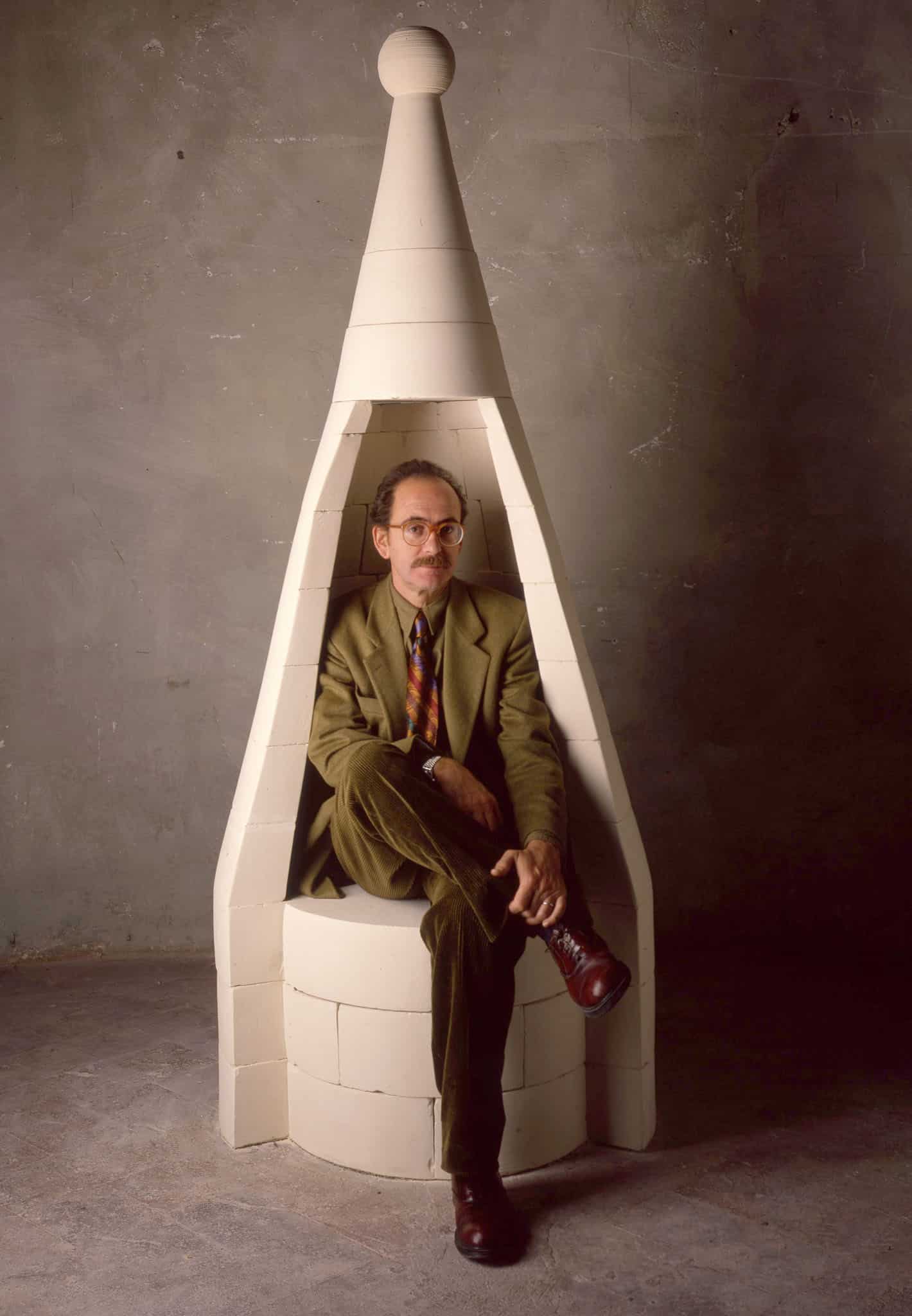

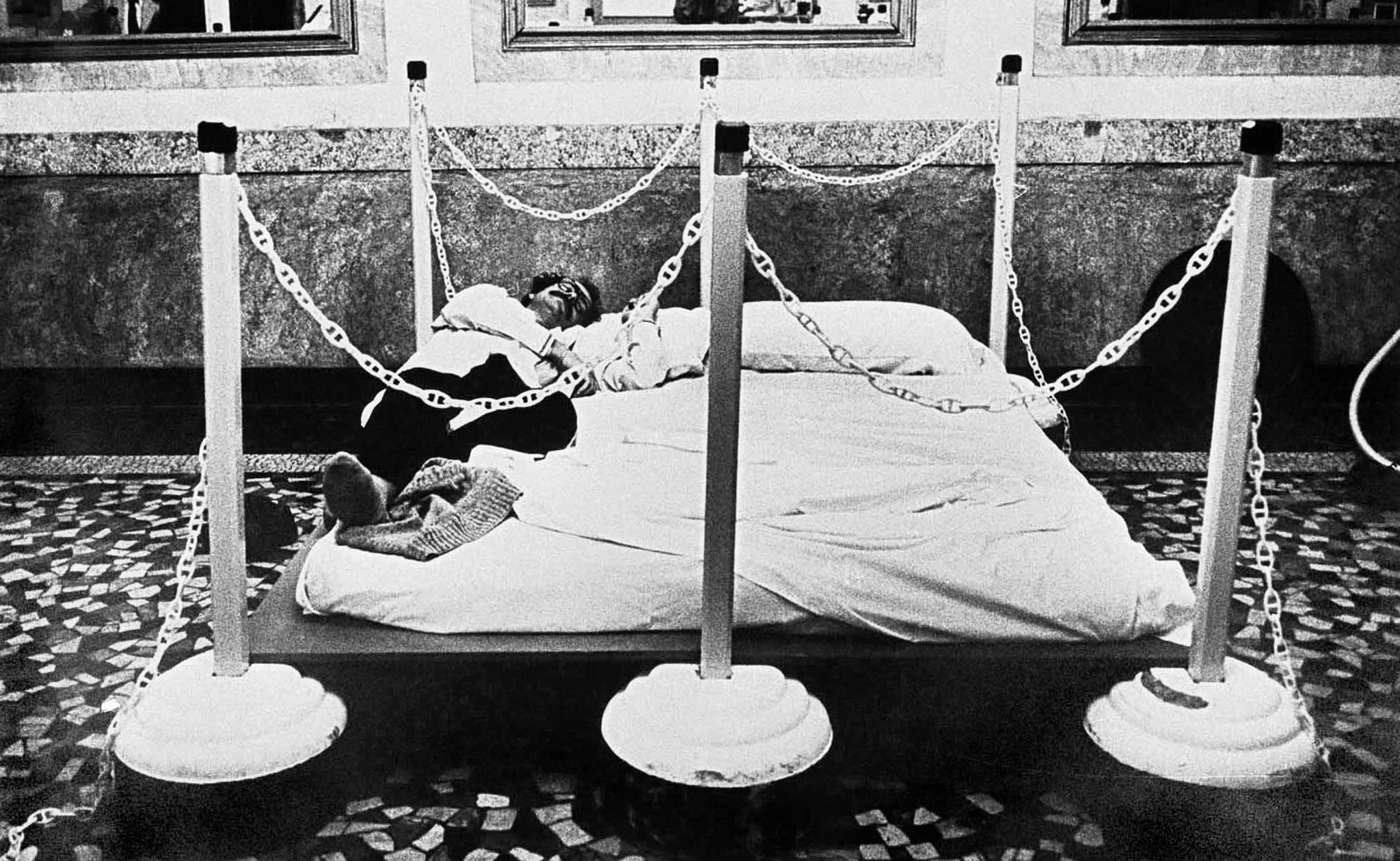

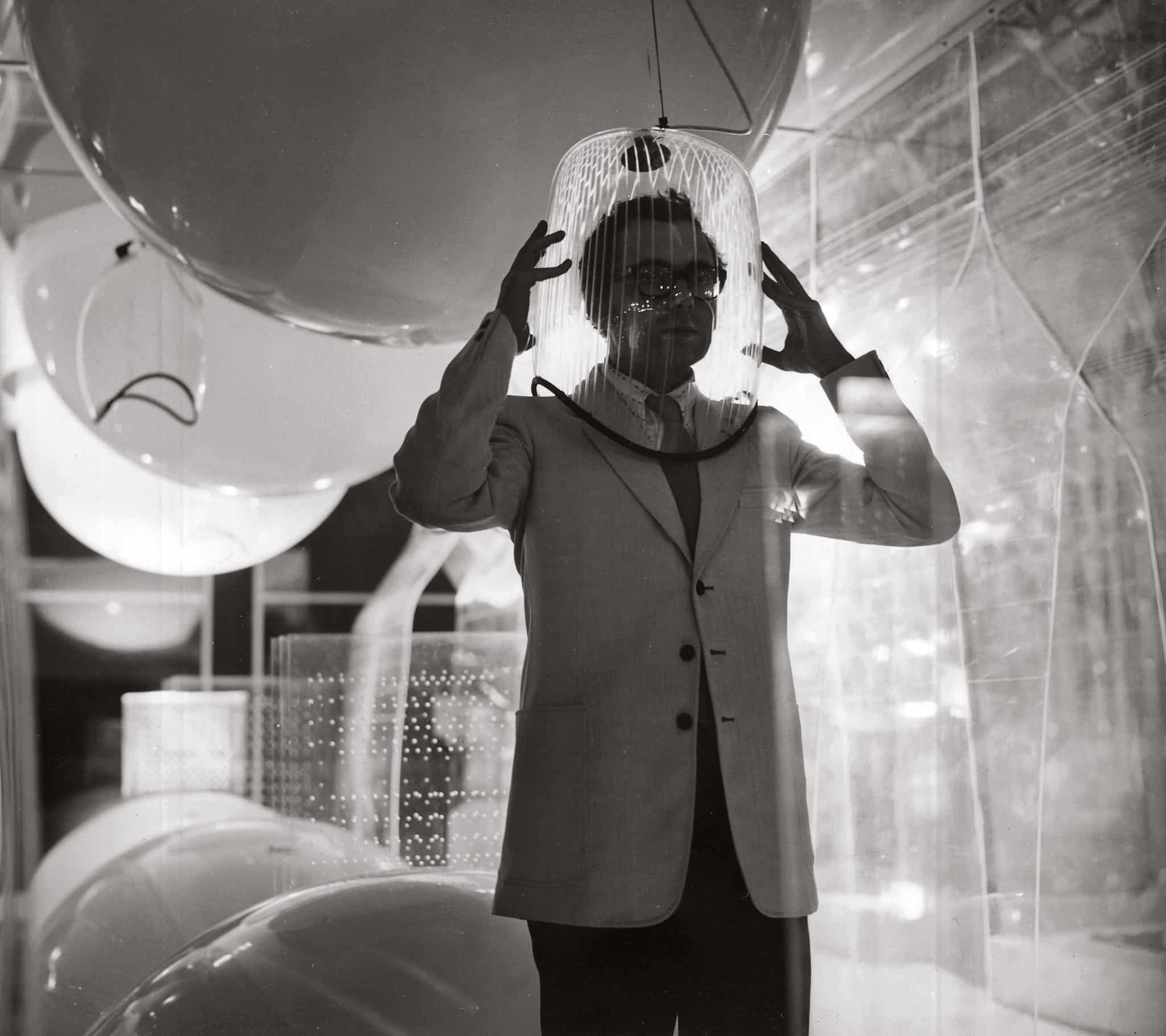

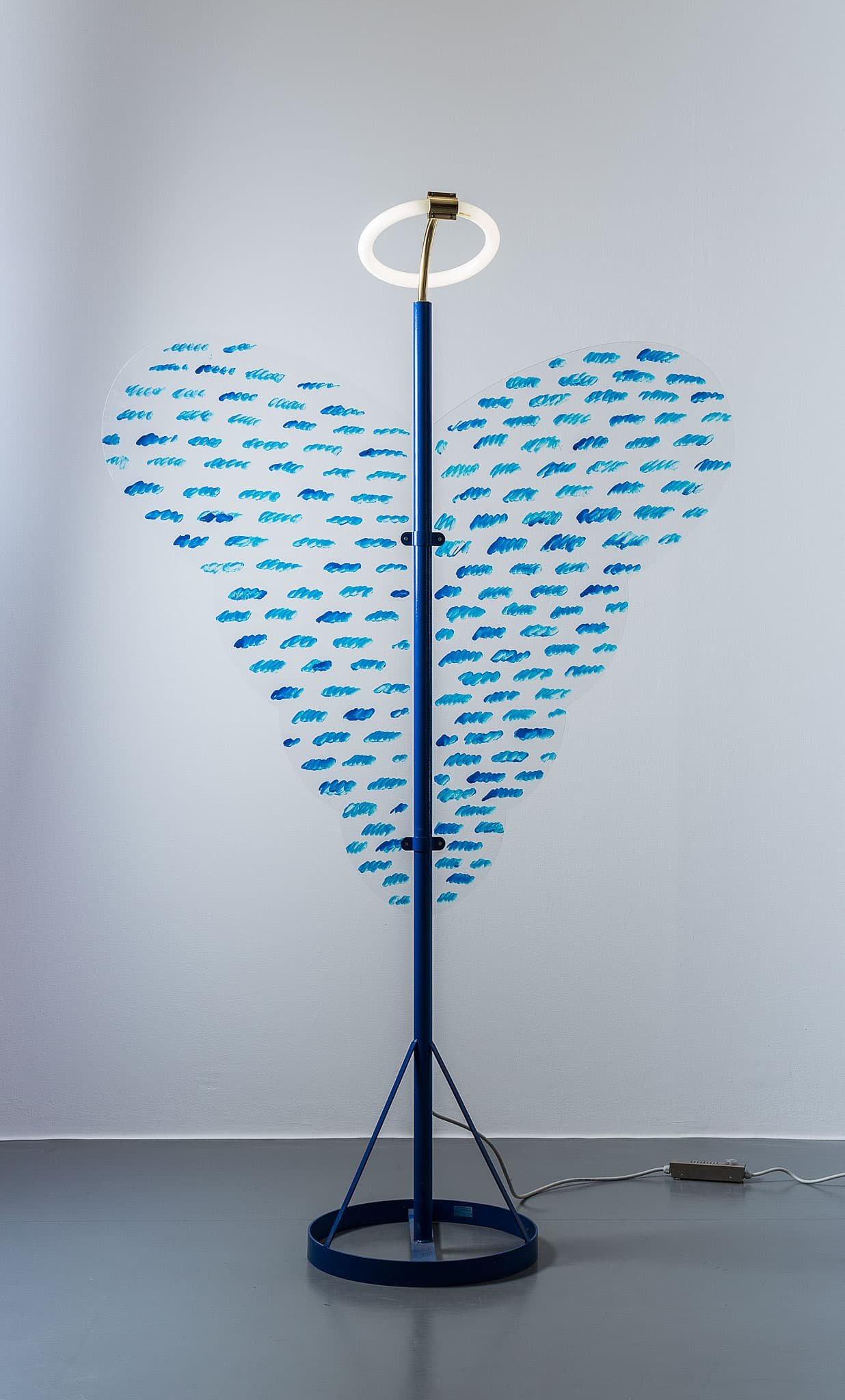

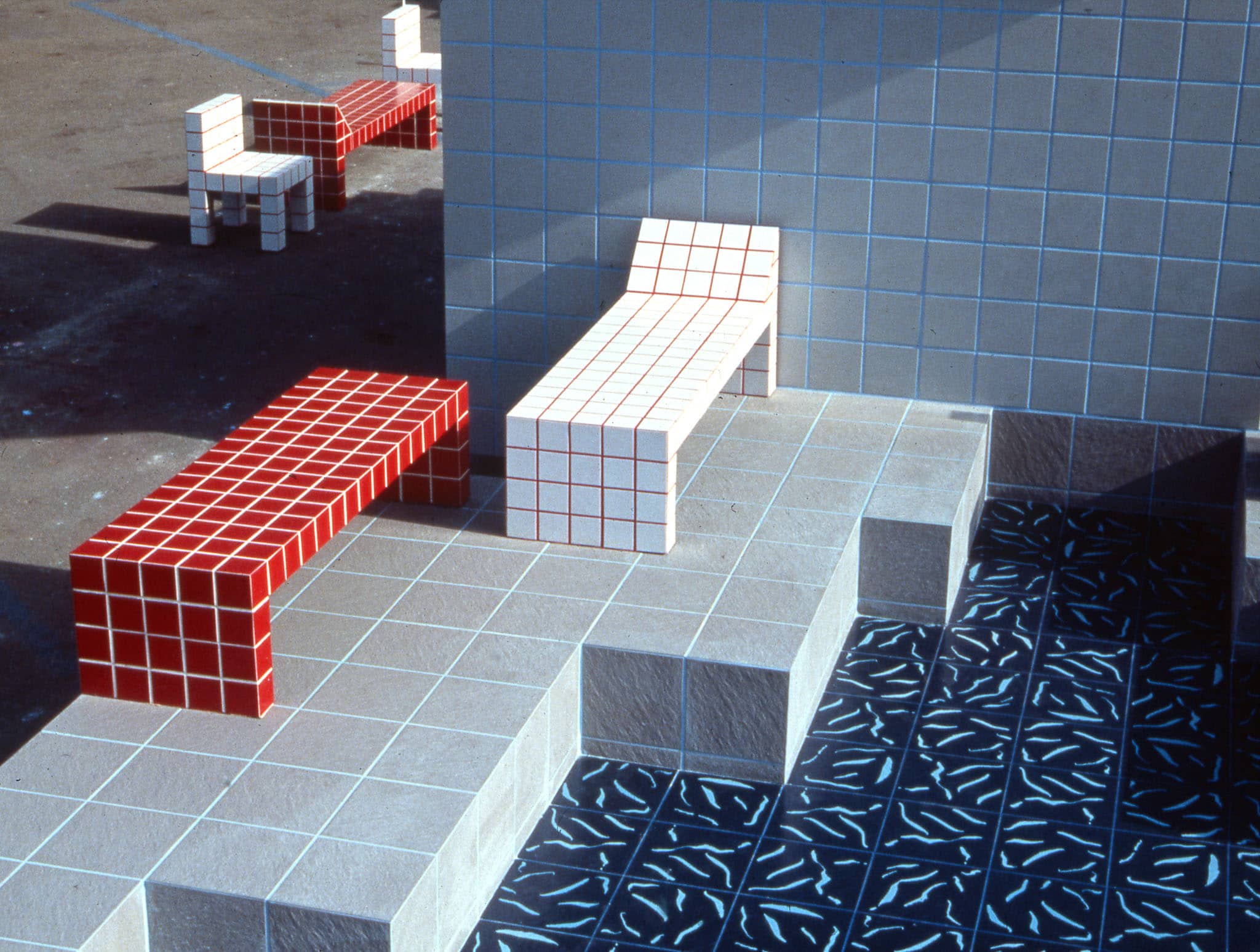

Milan: Many creatives of Italy’s bygone era are referred to as ‘Architetto’, irrespective of whether or not they’re really architects. Hence, when we met Ugo for the first time, that is what we called him too. He responded promptly, ‘No no! Non sono un’architetto!’ This is Ugo in his essence. It’s been his life’s pursuit to make sure he isn’t categorised as either an architect or artist but as a specialist, an expert: a maestro dedicated to the development of ideas that span multiple disciplines to bring together the idea of ‘creating’. His approach isn’t limited to the medium he first trained in (architecture) or those he branched into (design, filmmaking, music, cartoons, publishing); he’s also worked with the many greats minds of Italian radical design. In Global Tools, a series of workshops from 1973 to 1975, he collaborated with Archizoom, Superstudio, UFO, Pesce, Pettena, and Sottsass, among others, to promote the use of natural materials and traditional skills, again focusing on research and process rather than aesthetics or product. On his own terms he developed the Disequilibrating System in 1967, proposing a number of tools to revolutionise society, including Immersioni, objects which alter a person’s perception of reality through their physical surroundings to change their world view. Other ground-breaking projects include the Telematic House, presented at MoMA in 1972 as part of an exhibition on new domestic landscapes, a prophetic exploration of new modes for exchanging information between individuals in their homes and the city at large. He became an art director for Abitare il Tempo, the furniture show where, between 1986 and 1997, he staged annual ‘environments’, inviting artists to collaborate with artisans on multiple objects, integrating two formerly separate disciplines. Today, at 83, Ugo’s work has become more relevant than ever. Last year he produced Erbario, an entirely imagined botanical encyclopaedia poking fun at greenwashing trends. After several years of working closely with Ugo, we look forward to sharing his genius with a new generation of admirers.

close

close