You’ve expressed this absurdity in many posters as well. A famous example is the one where the Statue of Liberty is being put down the throat of a Vietnamese child.

I just did a poster that should be hanging in French schools, about the Shoah. But there again, it’s really hard. It’s a big swastika, and one end of it has a hand that’s grabbing two Jewish children. A lot of teachers say ‘we can’t hang this poster, it‘s going to scare the children’. But isn’t the Shoah scary? Excuse me? If you want children to be aware of it, you have to show them. It all happened only 50, 60 years ago. They have to be scared.

Even in Fornicorn, maybe your most controversial erotic work, there’s a child sitting between two adults in one of the drawings.

We have a farm here. We used to have a pig. My daughter called her Madonna. The dogs had a go at her—and the children were applauding. Excuse me, but it’s all relative. Of course, you need to take into account every child is different. I did this story about a boy who doesn’t want to be kissed by his mother, he just hates it. You can’t give this book to an orphan, because an orphan never had any parents, and the poor little orphan would be dying for one kiss. So everything is relative. I’d really worry if some of the erotic works fell into children’s hands. This is a big dilemma. I was born and brought up Protestant and Puritan. I’ve kept a lot of these values. And I definitely see that a lot of my adult work is not suitable for sensitive children. In the museum in Strasbourg, the erotic stuff is downstairs in the cellar.

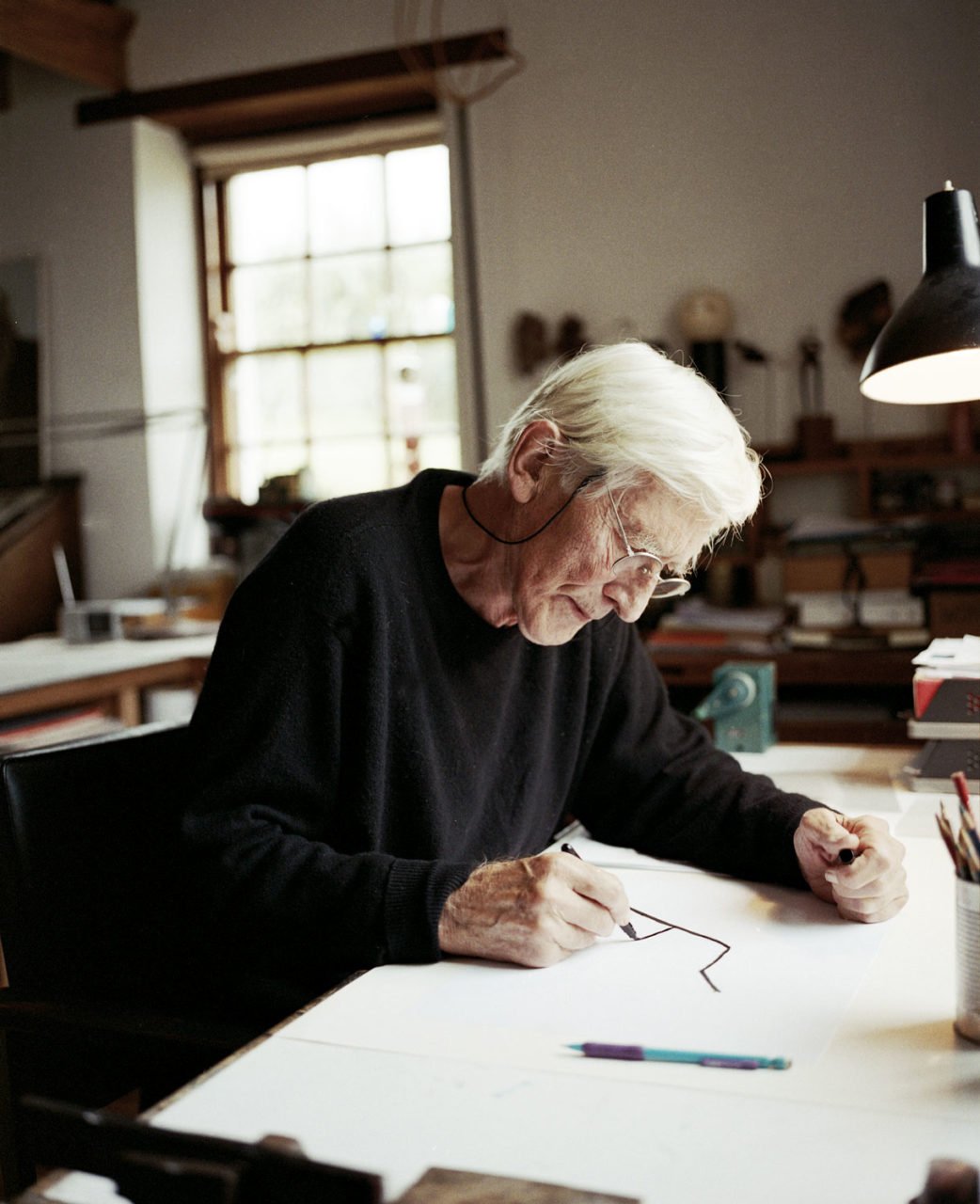

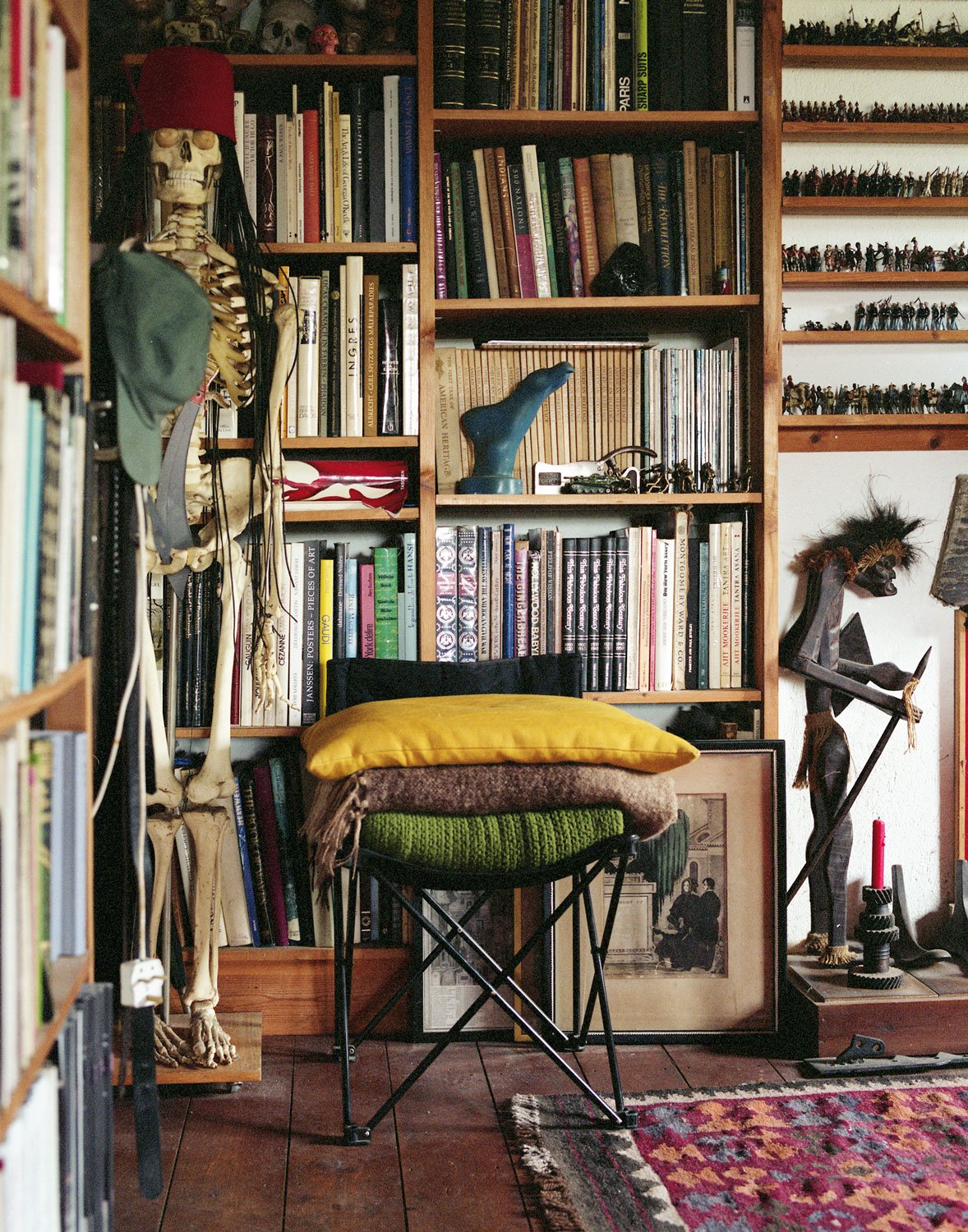

I noticed you have an Erich Kästner book in your studio toilet…

Ah, you’ve seen that. Actually, Erich Kästner is like my shadow. What he said to the children, about school. He said you should make fun of your teacher. Don’t believe everything your teacher is saying. Don’t believe everything adults are telling you. Or believe, but with a dose of doubt. And I like to instil doubt, because doubt is my philosophy. Don’t hope, cope. Reality is reality. If you instil doubt into a child, you have to make him understand everything else is ’why not?’. It’s for the children to find out if it’s true in the end.

Your philosophy was obviously hard to handle for the US government. At some point, your books were even blacklisted there.

And that was another reason I stopped doing children’s books for some time. In the beginning, my books sold well in America. America gave me my big chance. I discovered America and then America discovered me. It gave me all my first chances. Can you imagine, here I am, 25 years old, in 1956, with how much? $60 or something in my pocket. I stayed 15 years in New York. But when I was blacklisted none of my books were allowed in libraries, not even my children’s books. People who collect my early editions sometimes find a library card in them, with a seal saying ’Discarded’. With my political attitude and my erotic work, many people found it unacceptable that I should do children’s books.

With your experience, what would your suggestions be to someone who wants to write a children’s book today?

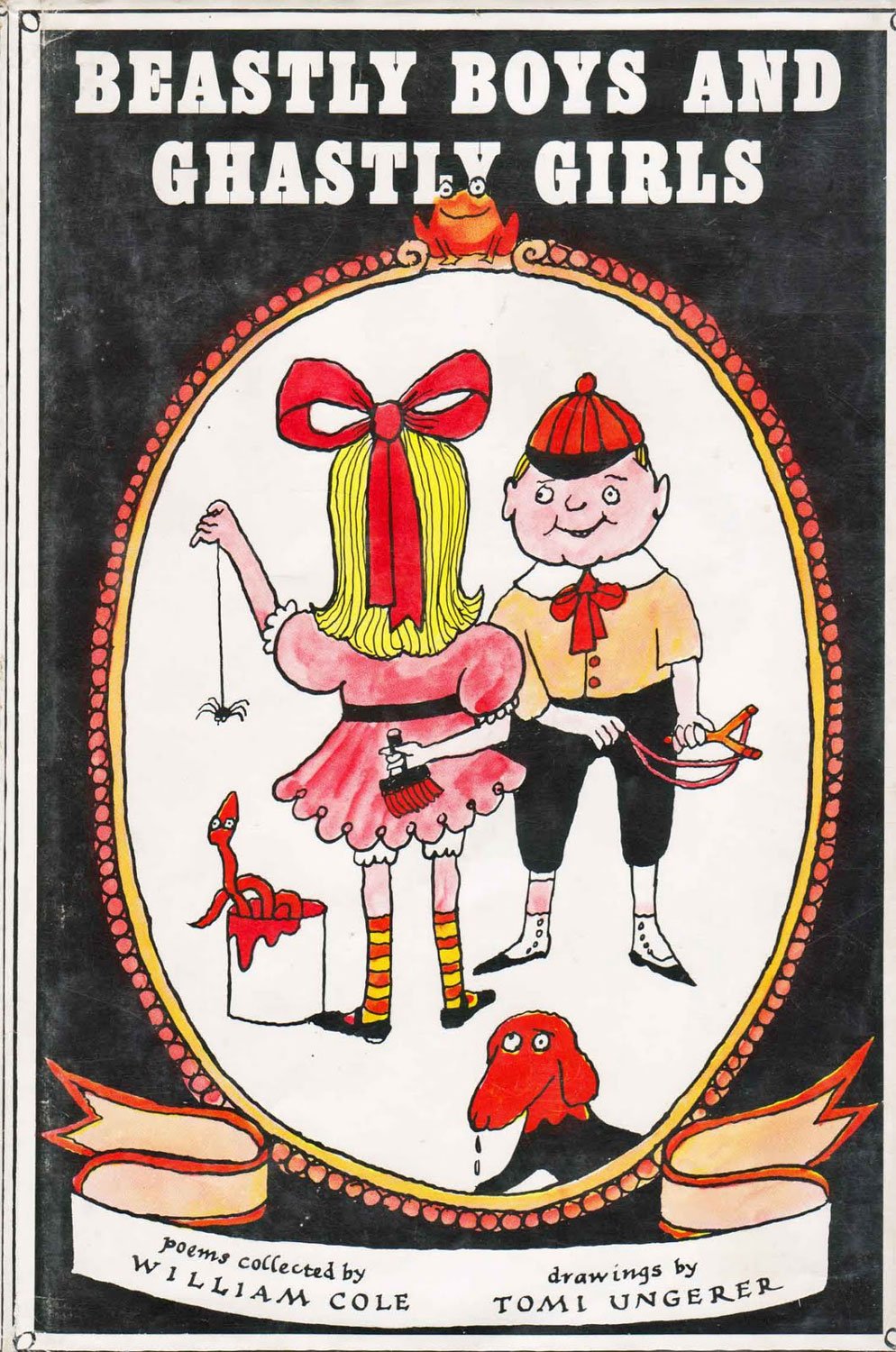

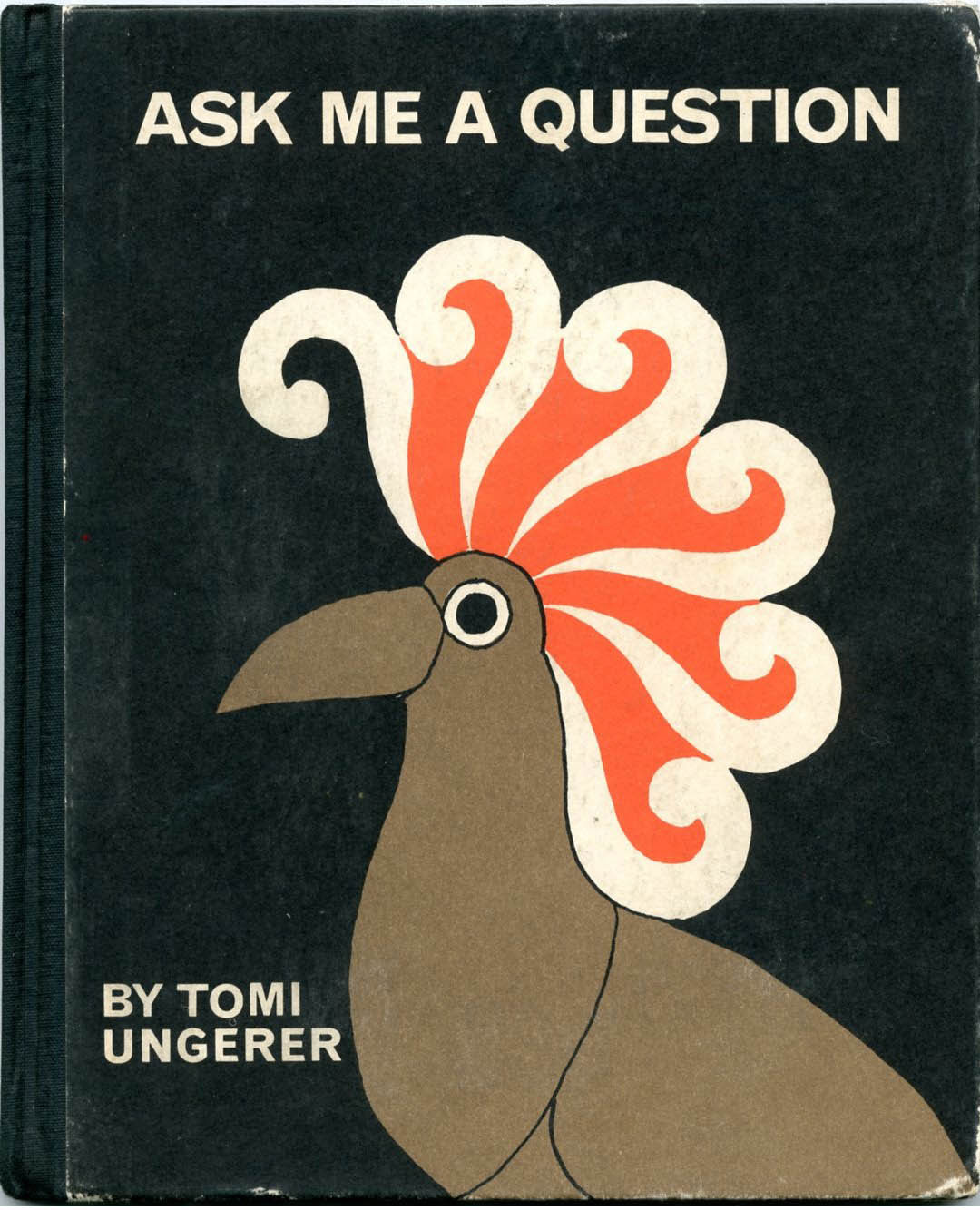

Most children’s books that have survived have been written and illustrated by the same person. Take ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ by Maurice Sendak. Or Edward Lear—a great inspiration for me—he also did his own drawings. And anybody can learn how to draw. In Victorian days, every young lady knew how to draw in her sketchbook when travelling. It’s a matter of discipline. It’s very easy.

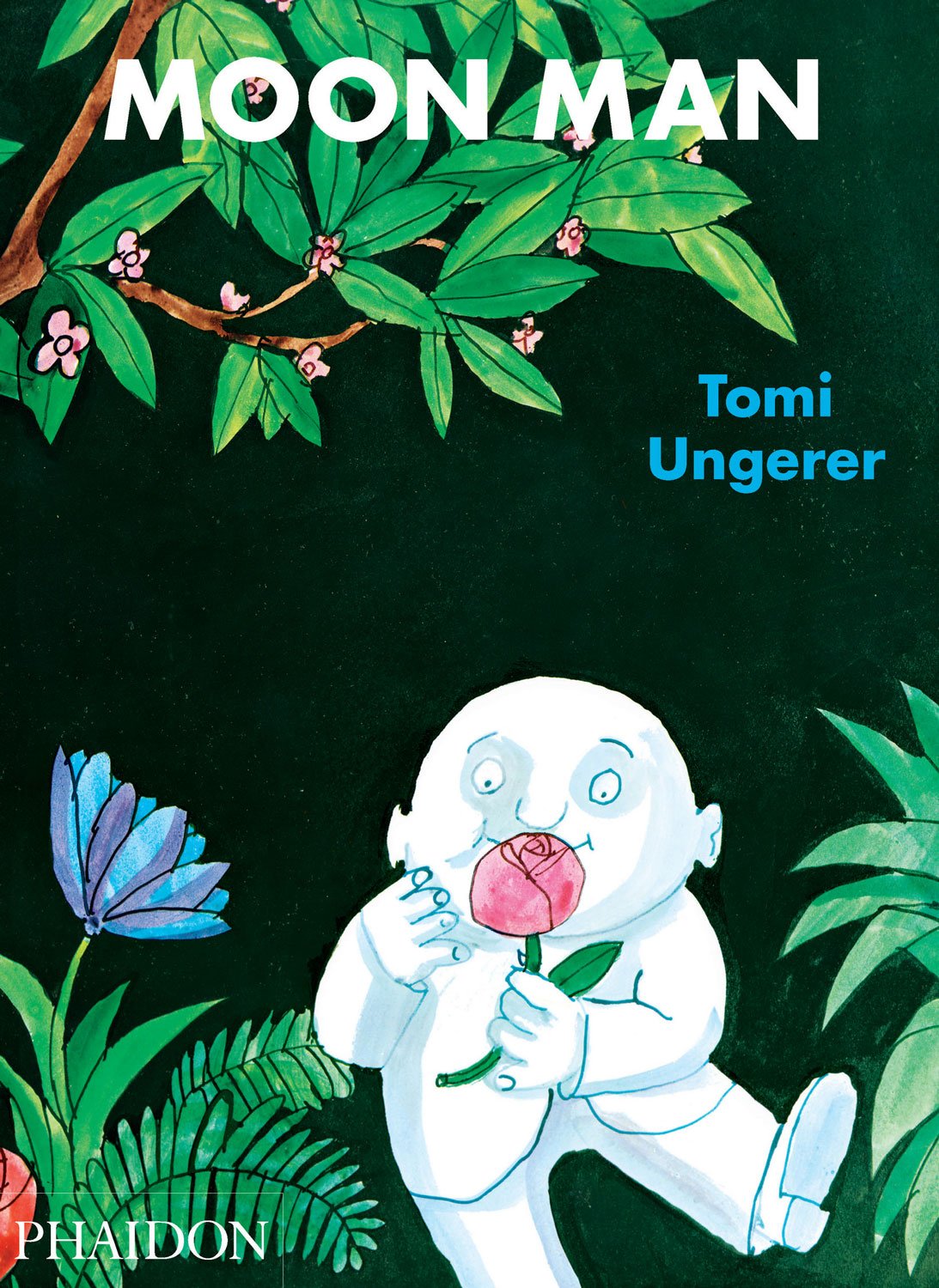

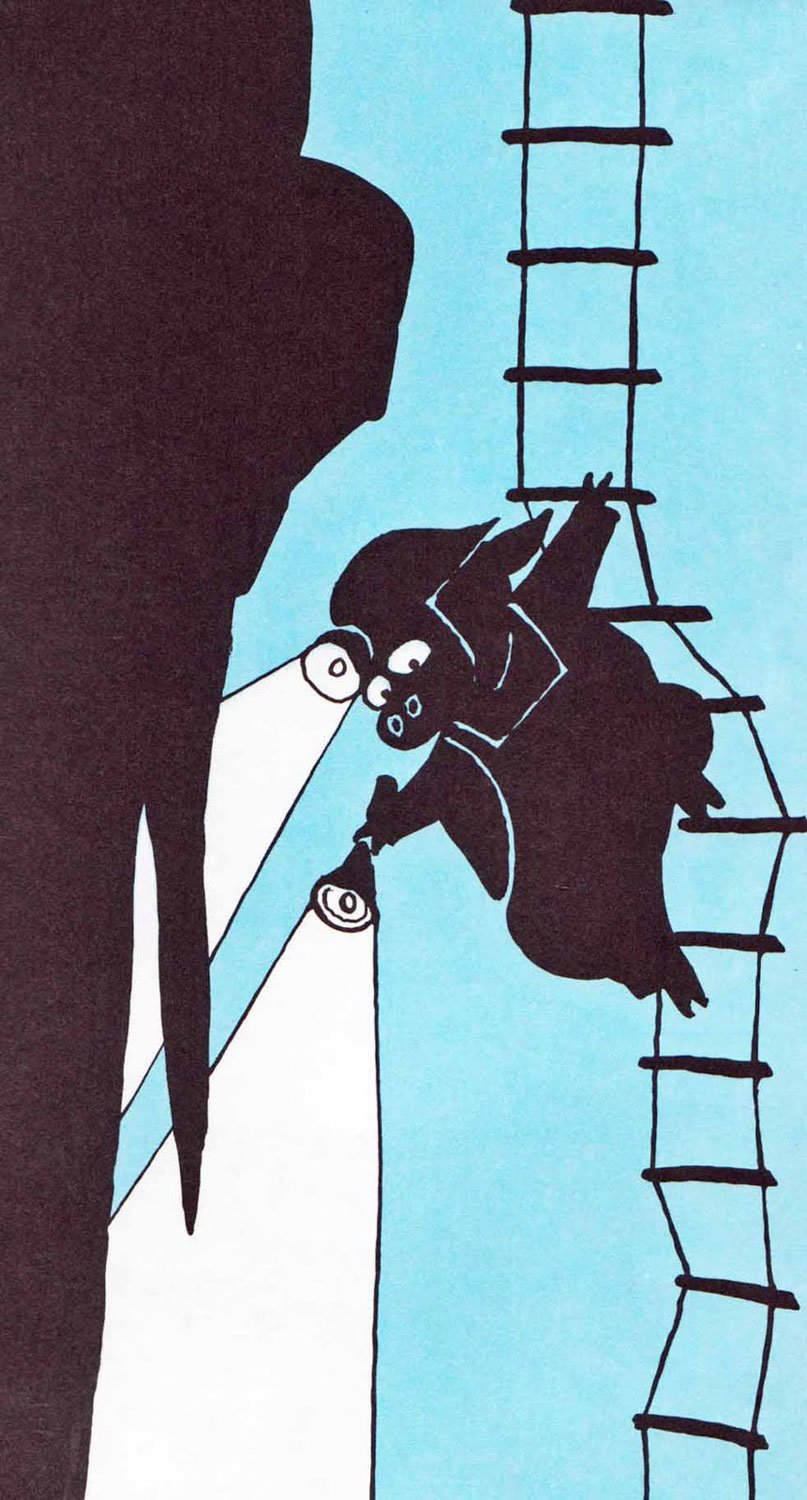

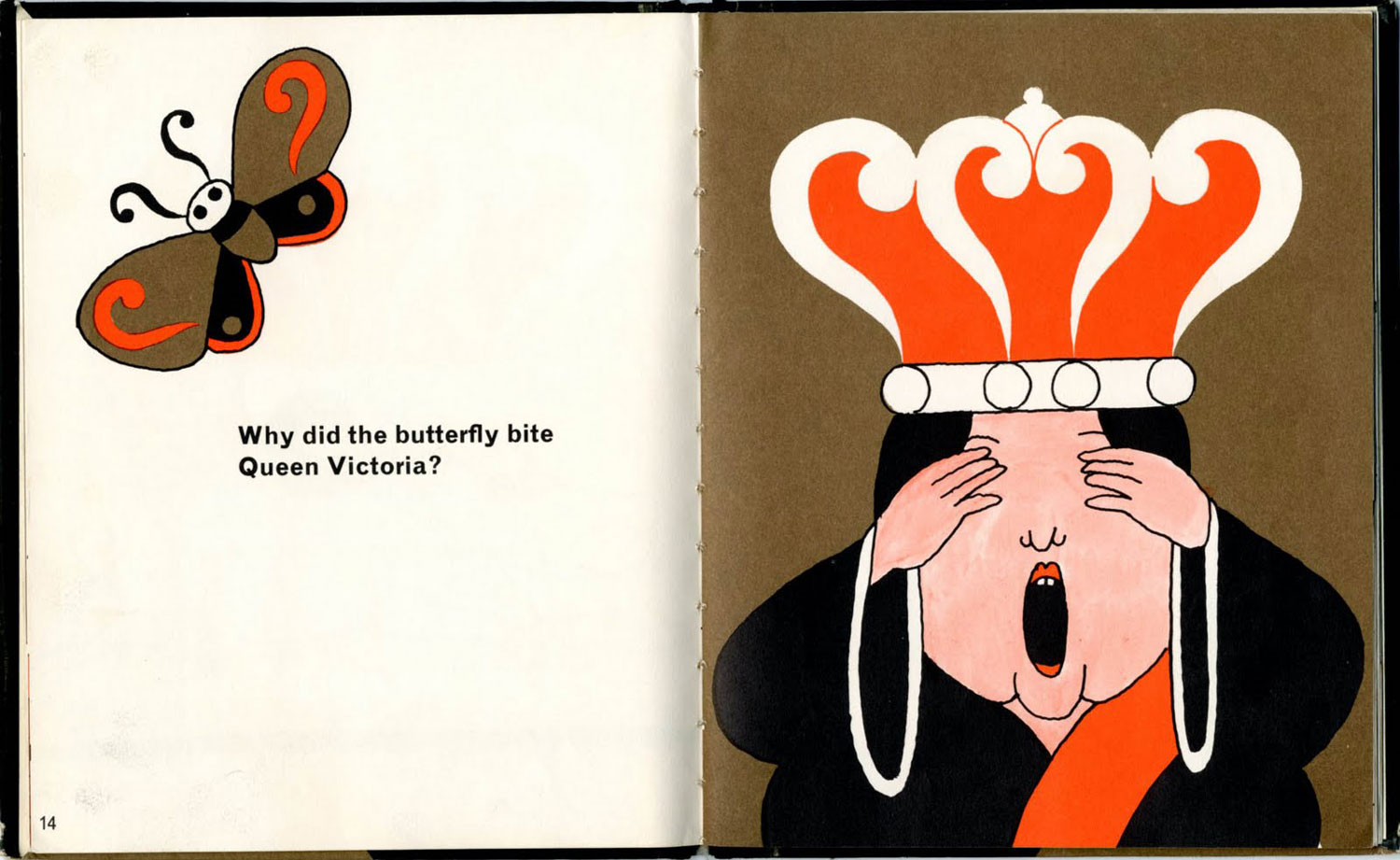

What about topics? You said there should always be an element of fear in a good children’s book.

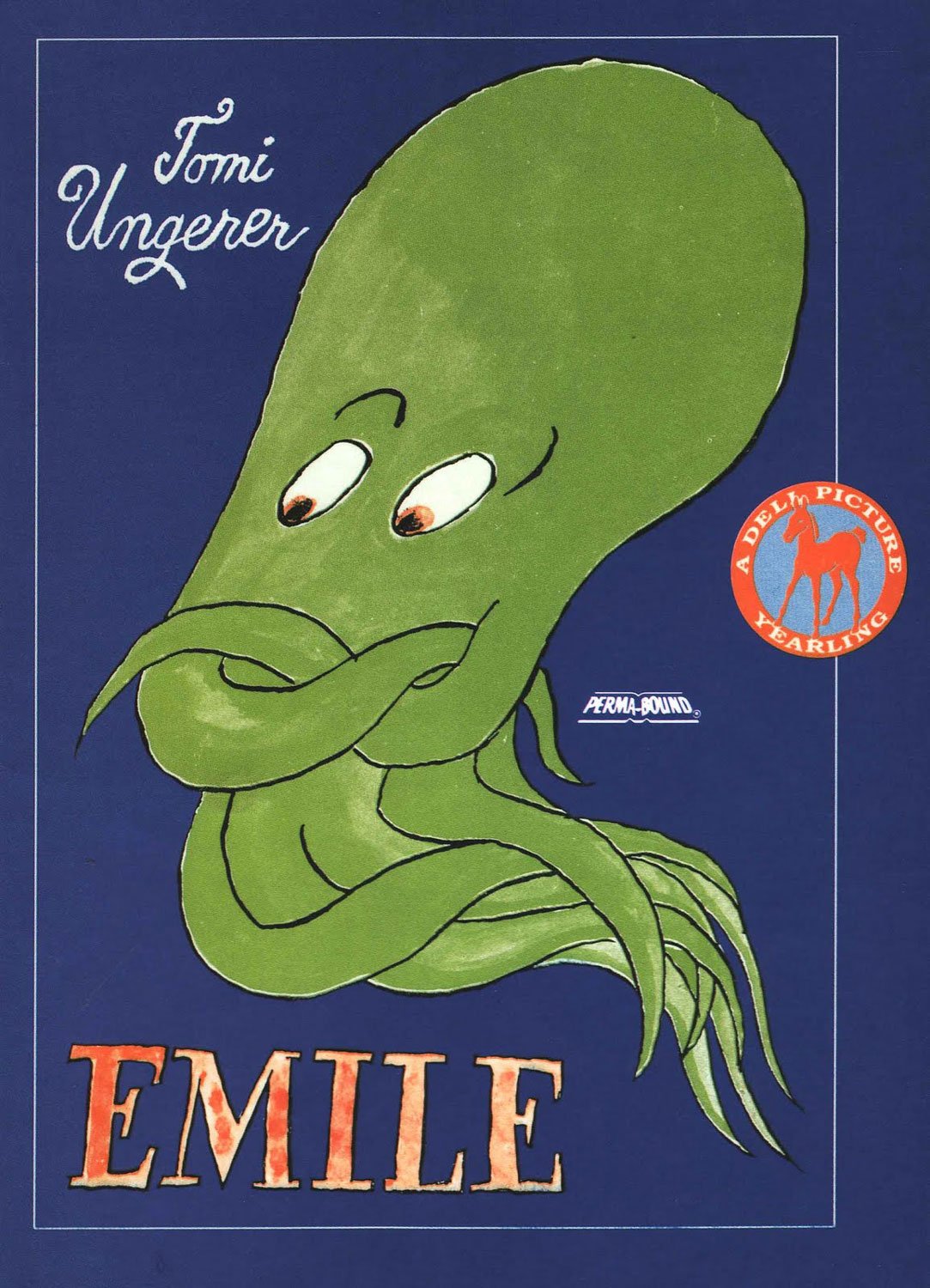

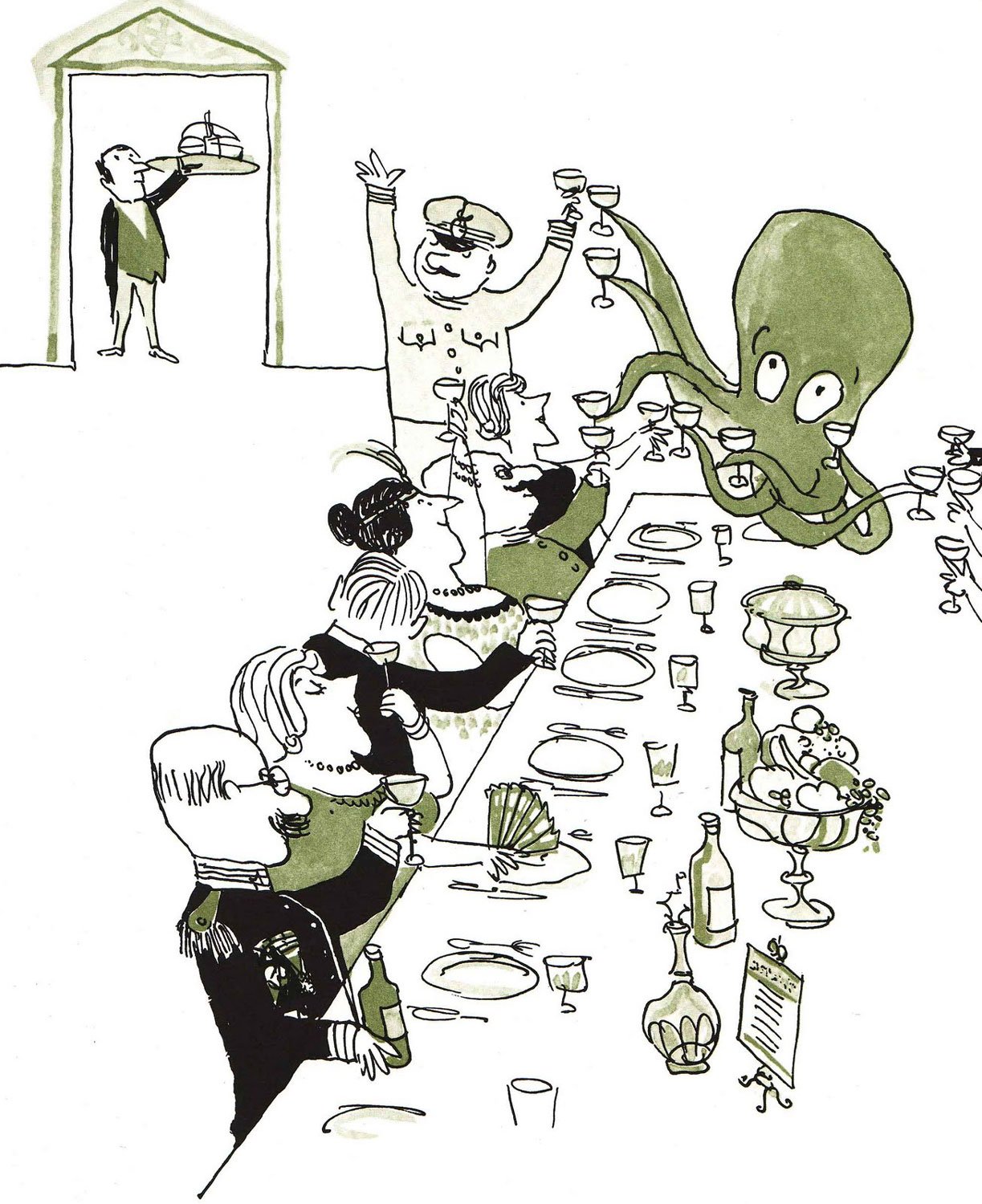

It’s like cooking. When you cook a meal, you add pepper, salt and so on. They’re the elements you need. So in a book, fear is just one of the elements. My earlier books were completely different actually, because they were all about animals rejected by humans because they’re disgusting or awful—octopus, snake, vulture. To show children, no matter who or what you are, you always have something others don’t have. Everybody’s got something. Even in the Nazi era, I wasn’t a very good student, and my teacher said, ‘Don’t worry, the Führer needs artists’. In this context, that was a nice thing to say.

close

close