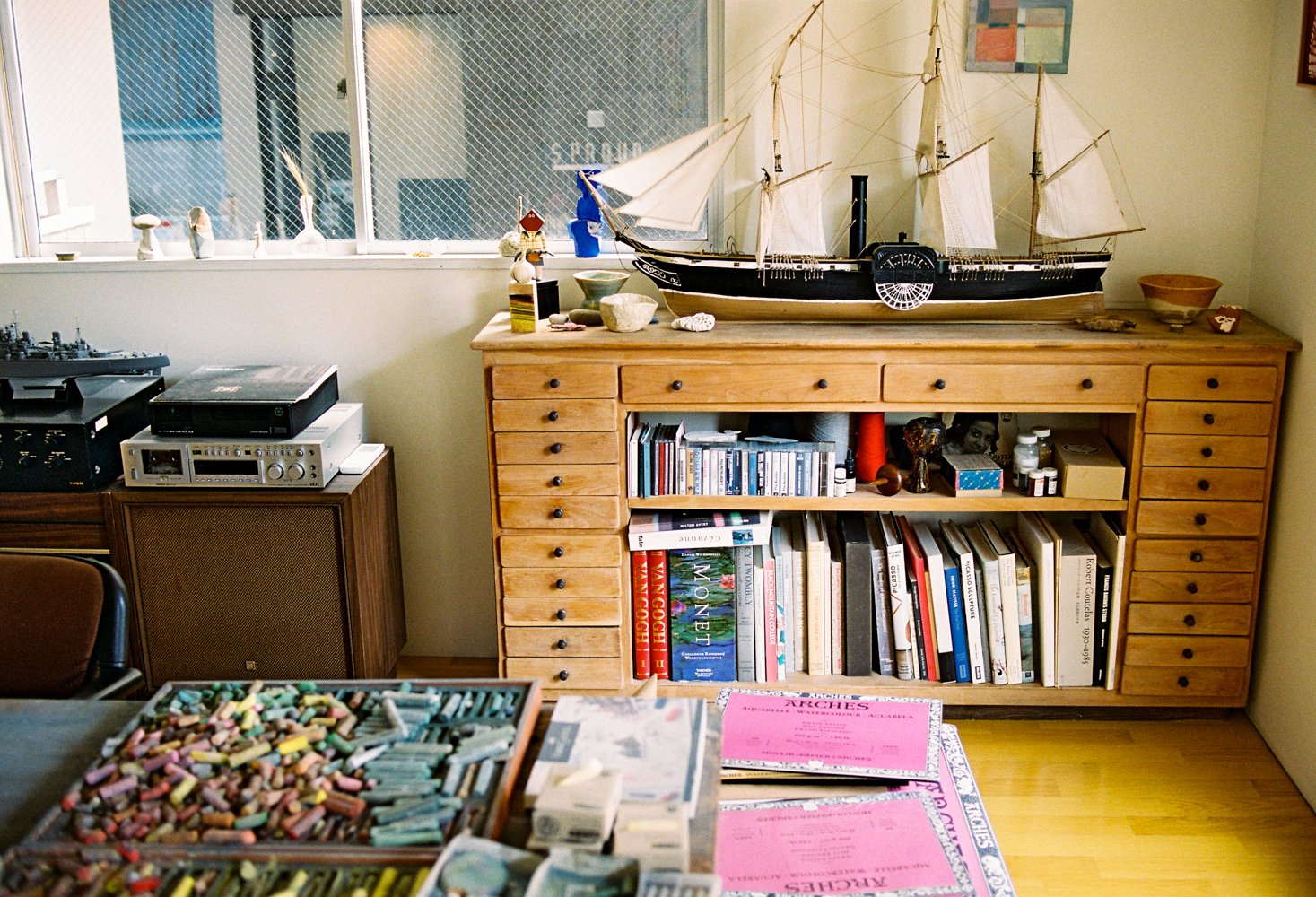

Kyohei Sakaguchi lives in Kyushu, one of Japan’s large southern islands, in a city called Kumamoto. He is an architect who hasn’t build any houses, but also is active in many fields. Kyohei is an author who has written more than 40 books; a musician who has released more than five albums; and an artist who had a solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum Kumamoto in 2023. His apartment is designed to fulfil each of these creative needs. There’s a writing room with a computer and many books, a recording studio with a piano, saxophone, guitars. The bathroom has been renovated so that he can play the drums ‘quietly’. On the dining table, there is an easel and pastel chalk.

While each of these activities keeps Kyohei busy, he still finds the time to answer calls to his own ‘Inochi-no-denwa’, a lifeline set up to help anyone with suicidal thoughts during a moment of crisis. His phone number is available on social media so anyone can call. After learning that the national lifeline service was unreliable, Kyohei started his own line in 2012. For over 10 years, he has been receiving about 5 to 10 calls a day. According to him, this lifeline is a space created by the exchange of human voices. It is public, and therefore he sees it as the most desired public facility.

Kyohei was diagnosed with bipolar disorder when he was 31 years old. He is very open about his depression; he recognises it as essential for his creativity. It is precisely because there are times when Kyohei is depressed and unproductive that he is able to feel and notice sceneries, sounds, and details that most people overlook. Kyohei’s sensibility allows him to honestly perceive everyday things as beautiful. His apartment reflects that unique warmth, the kind of place where you want to stay a little longer.

close

close