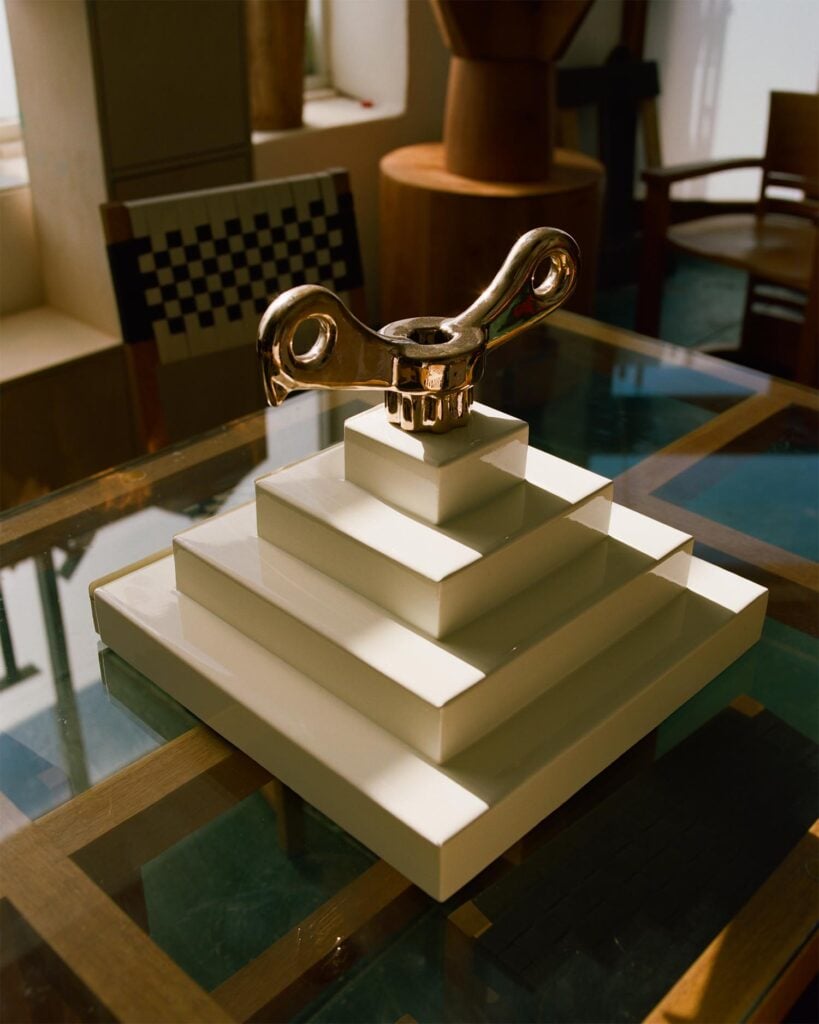

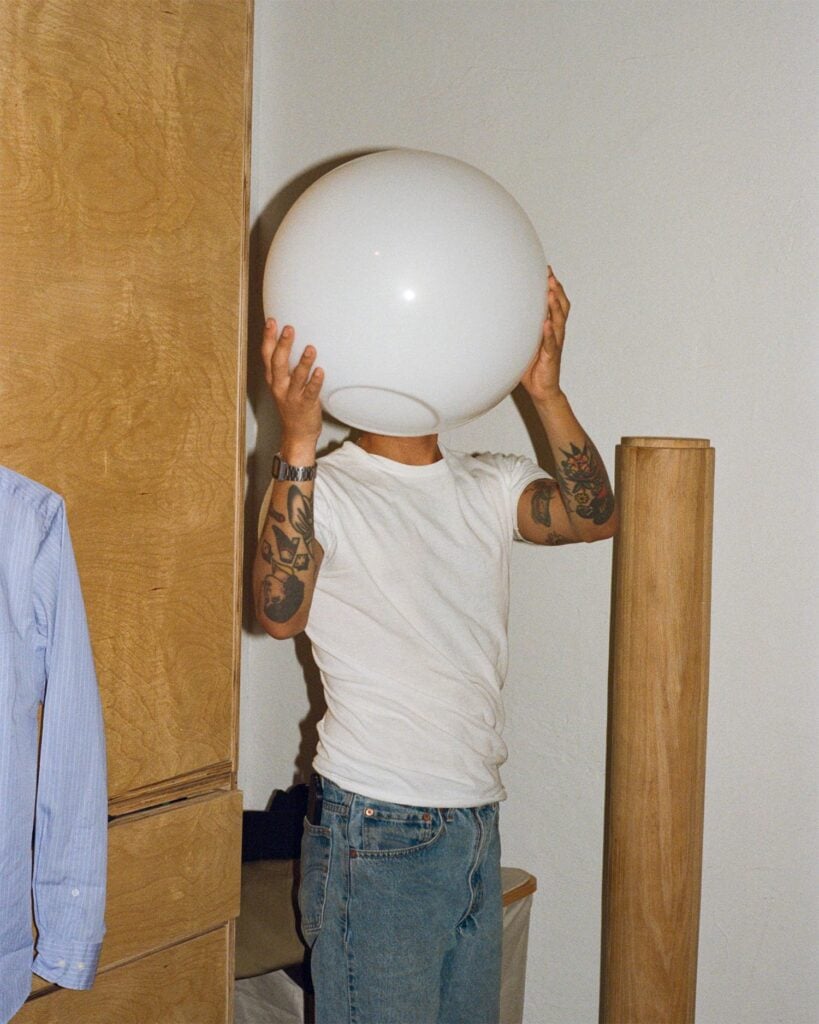

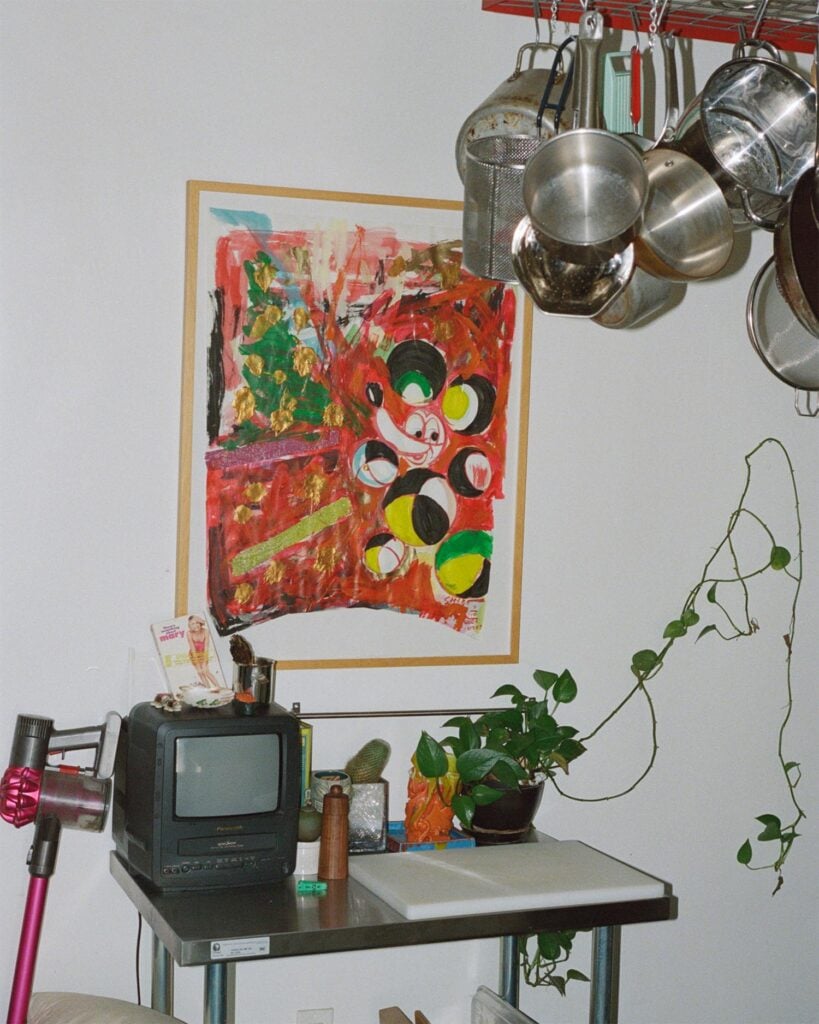

Los Angeles: Time passes slowly, stills, in Ryan Preciado’s home and studio in central LA. Chairs form loose circles around conversations that must have stretched into the night, left at slight angles where distant ideas gather again in morning light. Ryan’s designs experiment with function, ranging from domestic pieces to more ‘insecure sculptures’, elemental shapes painted with primary colours. These works are united in their concern for a human element, an awareness of how the leather of his Chumash Chair might embrace a body, how the feel of soft oak conjures memories of his grandmother’s home. That warmth likely extends from Ryan’s creative process, which leans into collaboration: in the local hardware store and auto shop where he exchanges ideas, in the friendships that have become a place of inspiration.

‘With rafa, I felt something shift almost immediately’, Ryan said. He met rafa esparza, a multidisciplinary artist and fixture in LA’s art scene, in the early stages of Downhearted Duckling, a show Ryan curated at South Willard to tend to his Mexican and Chumash heritage, reckoning with the exclusionary nature of formal galleries. rafa inverted Ryan’s invitation to join the show, contributing a portrait of Ryan in his Chumash Chair, his gaze steady amidst the texture and earth of the adobe on which it was painted.

There are stakes to these bonds, which transcend a vague or sterile idea of ‘community’. In the face of sustained protests against immigration policies and targeted raids, thousands of federal agents were deployed in LA in June in what the New York Times calls ‘a rare use of active-duty military forces on U.S. soil’. Backdropped by rows of armoured vehicles, LA residents formed rapid response networks to support those affected by the increased raids; restaurants opened their doors to offer protestors refuge from the heat and a place to rest; and neighbour marched hand in hand with neighbour.

A question of inheritance trails this conversation, where home is both the place where you are and a memory you inherit, no matter how distant the past. It lingers in the motor oil smell of Ryan’s recollections of his grandfather, in his grandmother’s holy whispers. ‘It all just makes sense when I start to listen’, he tells rafa. ‘Everything’s right there, and that’s exciting to me’.

—Apartamento

close

close