To say that the world was restless between 1968 and 1969 would be something of an understatement. Cultural change and radical self-awareness played no small part in the contemporary history of postwar Japan. Technology existed at the heart of pitting the human body against the hostility of space. The US Apollo program was desperate for the 1969 moon landing to defeat the efforts of its Soviet counterparts. As the desire to escape the earth continued, a small group of Japanese artists made their temporal approach to object-making and painting even more extreme, with the view of making no ethical distinction between the man-made and natural, sending their own radical nature out into the world. Science and technology seemed to force things in one direction, while the quiet theory-led group known simply as Mono-ha pushed things the other way, deliberately transforming the avant-garde with a school of its own making.

Mono-ha, thought to centre around Nobuo Sekine, Katsuro Yoshida, Susumu Koshimizu, Koji Enokura, Noboru Takayama, Katsuhiko Narita, Lee Ufan, Noriyuki Haraguchi, and Kishio Suga, was not the only group in Japan but it did constitute one of the most unique and widely represented movements. Groups like Hi-Red Center, Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai (Gutai Art Association), The Play, and Provoke were clear in their own reaction to events locally and globally. Kansai-based The Play sailed a styrofoam arrow up and down rivers during the Apollo moon landing (Current of Contemporary Art, 1969) in reaction to the conscious remapping meant by landing on the moon and claiming territory in the name of all mankind—a subtle dig perhaps at the land disputes Japan also experienced following the Second World War. Mono-ha represented something very different. On the surface, it seemed less interested in issues their militant cousins were preoccupied by. The group’s core membership was nebulous by nature and never explicitly defined. The idea of them existing as a ‘group’ only became more apparent with every exhibition, yet they avoided producing a manifesto as Gutai did before them, declaring in 1956 that ‘the human spirit and matter, opposed as they are, shake hands’. Like the group photograph taken in readiness for ‘Art in Japan since 1969: Mono-ha and Post-Mono-ha’ at Tokyo’s Seibu Museum of Art in 1987, they were much more enigmatic and seemed too distant to warrant a handshake.

‘OOX’ at Tokyo’s Muramatsu Gallery in January 1968 brought together 25 artists from Tama Art University (otherwise known as Tamabi), in Tokyo, including Sekine, Suga, and Yoshida. Nine months later, Sekine’s seminal land art sculpture Phase Mother—Earth (1968) made its debut at the first Suma Rikyu Park Contemporary Sculpture Biennale in Kobe. A study in both absence and presence, Sekine’s ‘Earth’ work was a cylindrical core of excavated earth, 2.2m in diameter and 2.7m tall, placed beside the hole it created. Seeing the sheer scale and simplicity of Phase Mother—Earth inspired both Lee Ufan, a Korean-born painter in Tokyo with a degree in philosophy from Nihon University (or Nichidai), and Suga, under the name of Ao Katsuragawa, to submit their reactions in written form to a critical writing contest organised by the art periodical Bijutsu Techo. Yet it wasn’t until 1970, with the roundtable discussion ‘Voices of Emerging Artists: Mono Opens a New World’, that the group became more aware of each other.

Turning away from the traditional notions of ‘school’ in Japan, founded in Western-style oil painting (or ‘yoga’), they neither leaned towards nor pushed away other groups known for confronting late 20th-century modernism: Arte Povera, Supports/Surfaces, and Anti-Form. Yet Mono-ha strangely found itself informed by neither side. Koshimizu openly stated how uncomfortable they were being labelled Mono-ha—‘ha’ describing ‘the school of’ and ‘Mono’ defined as ‘things’. It wasn’t until much later that the name and use of ‘ha’ was adopted by critics eager to give the nameless group some sense of form, despite their wish to stand apart from the establishment and institutions charged with steering postwar artistic practice.

During a symposium for the 10th Contemporary Art Exhibition of Japan: ‘Man and Nature’ (1971) the socialist art critic Hariu Ichiro argued that artists should develop new languages through existing means to describe a harmonious form of nature rather than reach for something nameless and less apparent. Ufan, who was taking part in the exhibition, protested, claiming to have never defined what he or the group did as ‘nature’, or indeed ‘natural’. ‘Nature is about overcoming one’s confrontation with artworks. Experiencing art is about our desire to be surrounded by this environment of a shared space with artworks. To confront only leads to projecting one’s own image of what one wants to see out the other work by objectifying nature and the world’.1

Despite its origins, Mono-ha was never concerned with local geography. Inspiration stemmed as much from an awareness of Carl Andre, Richard Serra, and Jannis Kounellis, while painter and avant-garde pioneer Yoshishige Saito, a tutor at Tamabi, was keen for them to focus on a more personal territory as much as anything else. Saito had brought back exhibition pamphlets from the first Minimalist shows in New York, picked up during an overseas trip, and showed them to his eager students, including Suga. Careful not to overstate this brave new world of expression, he stressed that they focus on thinking closer to home rather than latch onto the rigid formalism of what must have felt like a world apart, of no real consequence to the world they knew most.

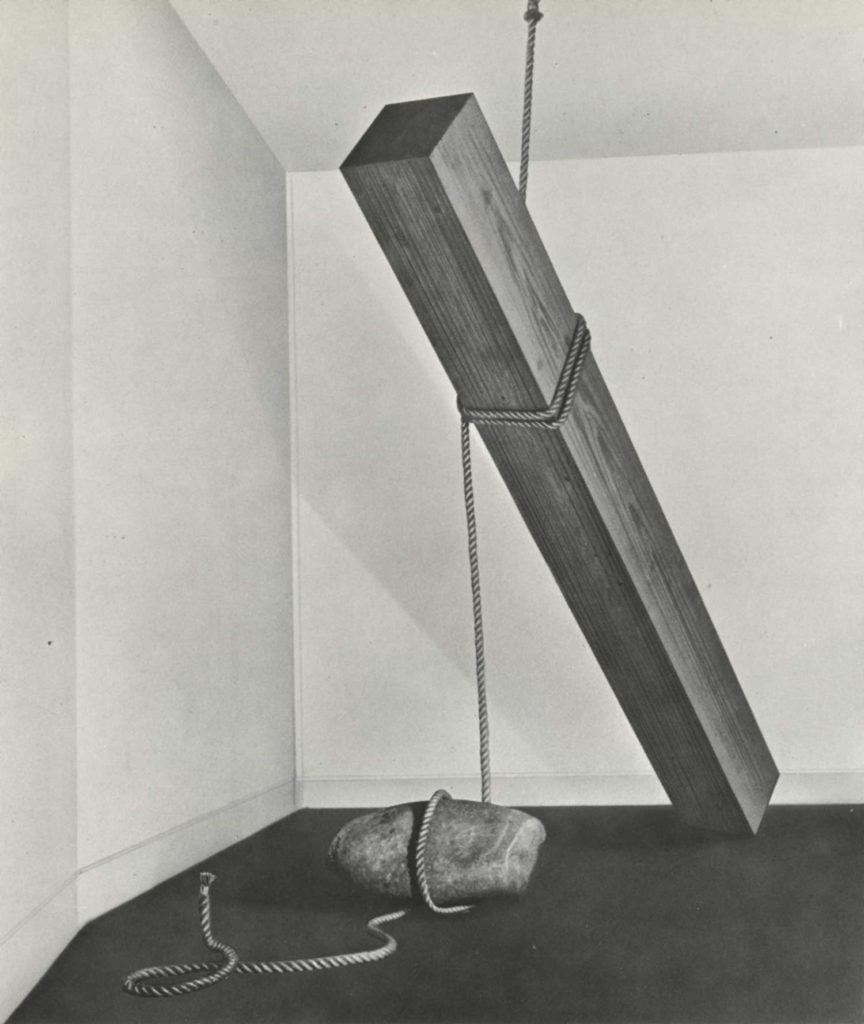

Lines of thought were now being thrust through the framework of painting and object-making, focusing on notions of fields, optics, transience, and immateriality. For Suga, the momentary use of liminal materials both hard and soft meant that painting and sculpture looked indistinguishable at times—Infinite Situation II (1970)—where preparation and construction were just as important as the work itself. While Suga reworked boundaries of wood, stone, concrete, and wax, Sekine sought experiences that absorbed the surrounding landscape, reimagining an element like granite to be as light as air, bridging a gap both physical and philosophical in nature. Even though it is clear with Phase of Nothingness (1969–1970), the weight of one material is carried impossibly by another, and his concern for rethinking inert materiality as being agile sparked the interest of others struggling to find a voice of their own; this new materiality carried with it a sense of victory over the cultural upheaval they struggled to attain.

Susumu Koshimizu’s Paper (formally Paper 2) (1969) and Lee Ufan’s Landscape I, II, III (1968), and the more recent Relatum—dynamics place (2008), are a performance of sculpture and painting. Each carefully placed material and block of colour describe their shared limitations, expressing how one artwork would visually and physically pick up where the other one left off. Katsuro Yoshida’s Cut-off (Hang) (1969/1986) and Koji Enokura’s Place (1970) and Symptom—Floor, Hand (P.W. No. 51) (1974) are as much about the space they were placed within as the actual material that was hung or laid on the floor. In every instance, artworks seem to question the nature of their own presence, expressing tensions between the gallery and viewer, as well as the ‘radical doubt’ embodied by every brushstroke searching for a language beyond the formal practice of painting. Mono-ha’s reputation as a performative force grew stronger with every mark. Both the 1969 and 1971 Paris Youth Biennale exposed them to a wider audience and brought them in direct contact with many more names they were already familiar with: Sol LeWitt, Bruce Nauman, and Sam Francis, to name but a few. Several years after Mono-ha disbanded, ‘Seven Italian Artists and Seven Japanese Artists’ at the Italian Cultural Institute Hall in Tokyo (1976) sealed their reputation as major figures in contemporary art of the late 20th century.

It is interesting that while the world they came into faded away with little effect, Mono-ha persists, despite not formally existing in the first place. This might be explained by the stoicism of cities like Tokyo in the ‘60s and ‘70s. ‘Out of this chaos’, explains artist and filmmaker Tadanori Yokoo, ‘this unknown energy was boiling up. There was Japanese traditional culture which I wanted to protect. Another side of me really wanted to destroy it. Although it wasn’t like my body was splitting in two, these feelings lived together inside me’.2 The collapse of the student movement in the late ‘60s and the profound sense of failure felt in the aftermath of confronting authorities saw many of the period’s cultural figures move away from documenting outside struggles to picturing internal worlds. Experimental filmmaker Toshio Matsumoto famously swapped the industry of vibrant youth culture seen in For the Damaged Right Eye (1968) for the spiritual enlightenment and geometry of Everything Visible Is Empty (1975), Black Hole (1977), and Engram (1987).

The success of Mono-ha could be defined by its insistence that work draws from the inherent nature of material and not the object. As Suga himself suggests, drawing out latent characteristics that seem as if they have been there all along is a way of investigating something unknown, something intangible. The legacy of Mono-ha continues despite its language being heavily berated by critics in subsequent years. By 1972 the group began to make less sense as core members left to focus on their own practice, moving away from Tokyo altogether, as Koshimizu did in late 1973. Exhibitions, such as ‘Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha’ at Blum & Poe Los Angeles (2012) and ‘Tribute to Mono-ha’, which is currently on show at Cardi Gallery in London (2019), continue to shed new light on how broad the group was in terms of painting, sculpture, performance, and experimental film. Suga’s re-staging of his Law of Situation (1971) installation at the 2017 Venice Biennale, as well as ‘Situations’ at Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan (2016), revivified a wealth of earlier work by employing newer materials. Restrained at first, the work of Mono-ha continues to be as agile as ever. Works still exert their own state of excitement, and almost all question their own existence: objects filled with the hope of being something very different. ‘If we do not destroy the concept of the material in objects’, remarks Suga, ‘we will be unable to make new objects from a new standpoint’.3

1 Mika Yoshitake, Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha (Los Angeles: Blum & Poe, 2012), 22.

2 Under the Skin (2011). Documentary, Japan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUi2eGEr3oo.

3 Doryun Chong, Postwar to Postmodern, Art in Japan 1945–1989: Primary Documents (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 225.

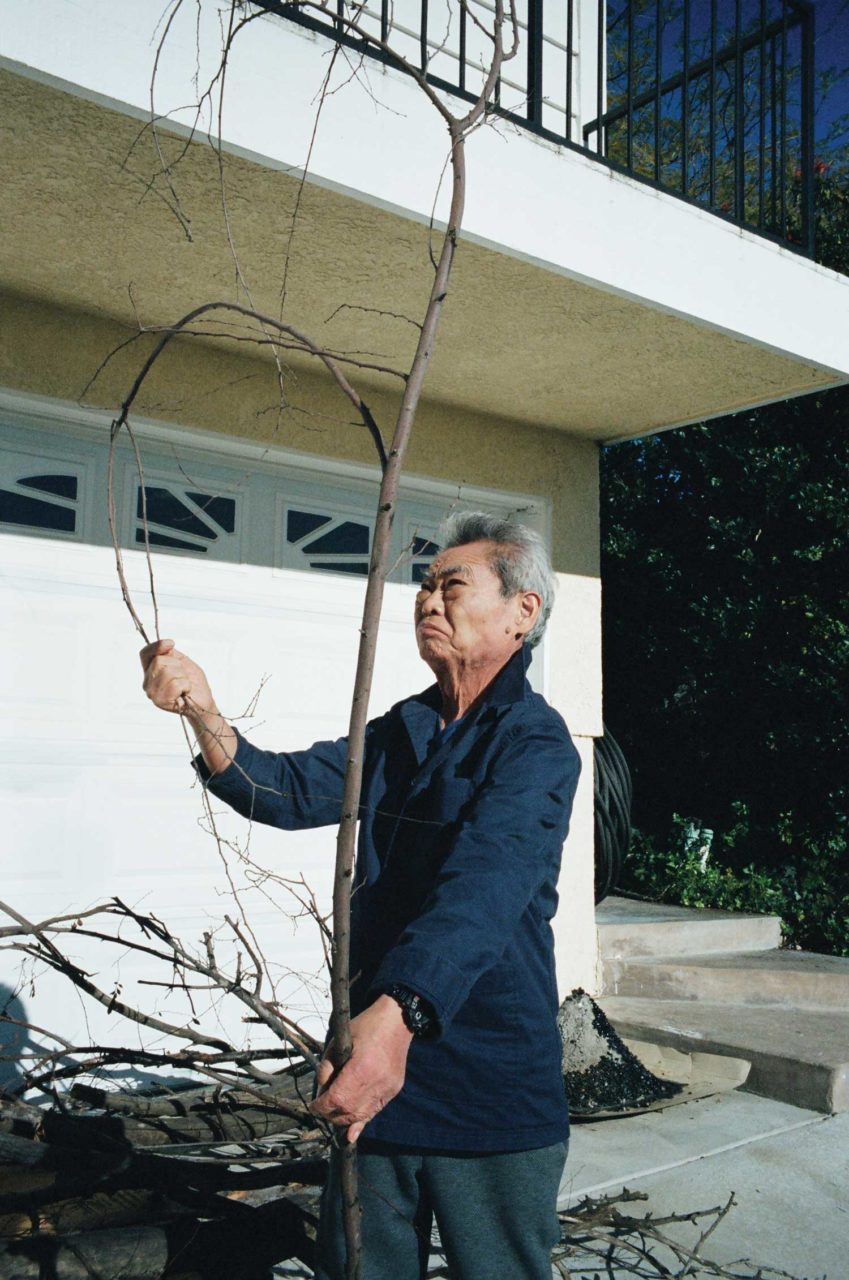

On May 14, 2019, Sekine passed away. He was 76. Born in Saitama Prefecture, Tokyo, in 1942, he later moved to America, relocating both his artistic and family life to the Palos Verdes hills of Los Angeles. A new interview in issue #23 of Apartamento magazine features the enduring image of him staring out to sea, surrounded by a bare minimum of clutter and artwork. The distraction of an ocean view, outstretched towards Japan, is all the distraction he needs. But the distraction is not a worthless one. Even the act of looking becomes a way of making something from nothing, responding to what is absence and not there. He will be greatly missed.

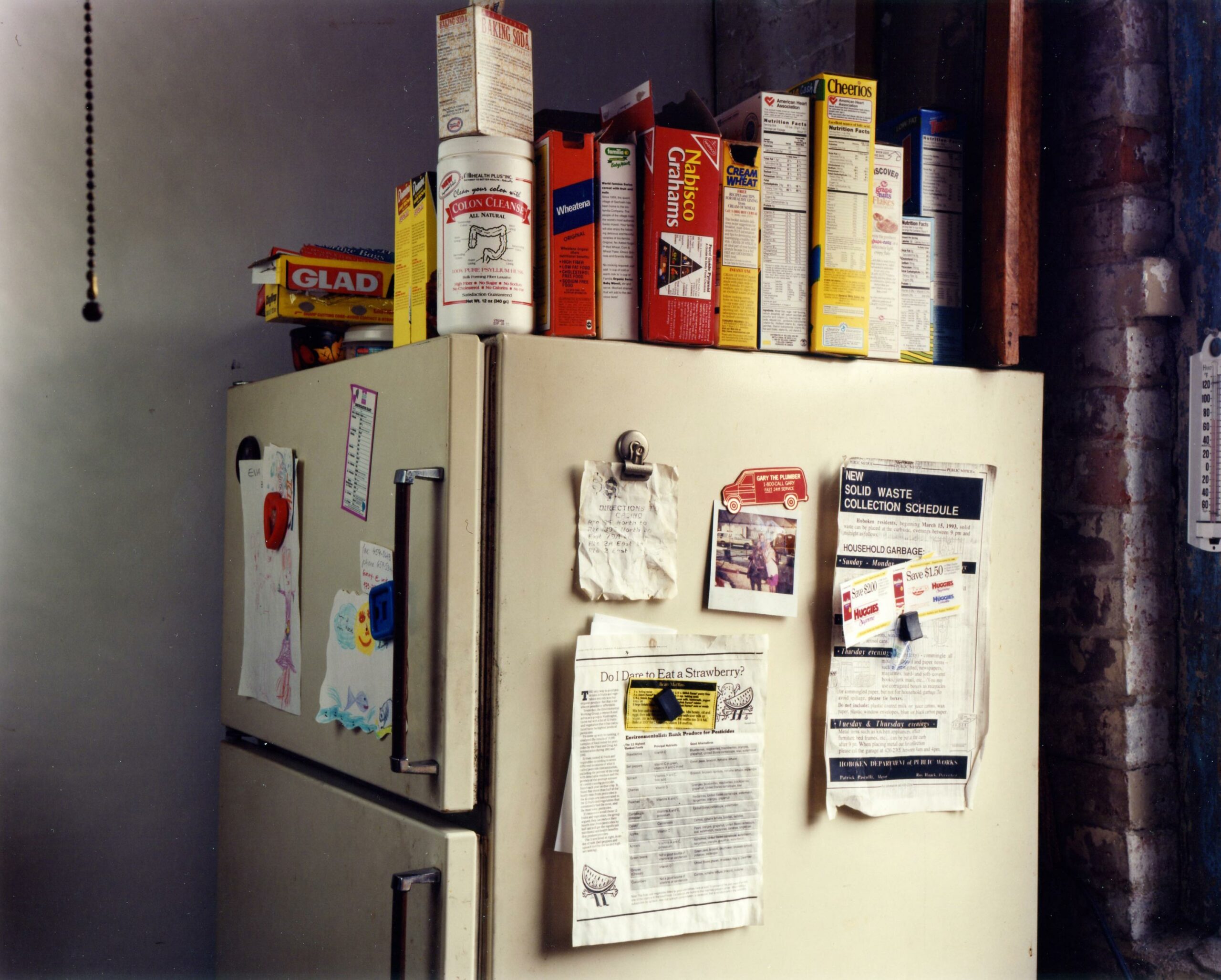

Selection of photos from issue #23 by Max Farago

close

close