Video coming back soon!

Apartamento magazine issue #31 is officially OUT NOW! Click here to get your copy.

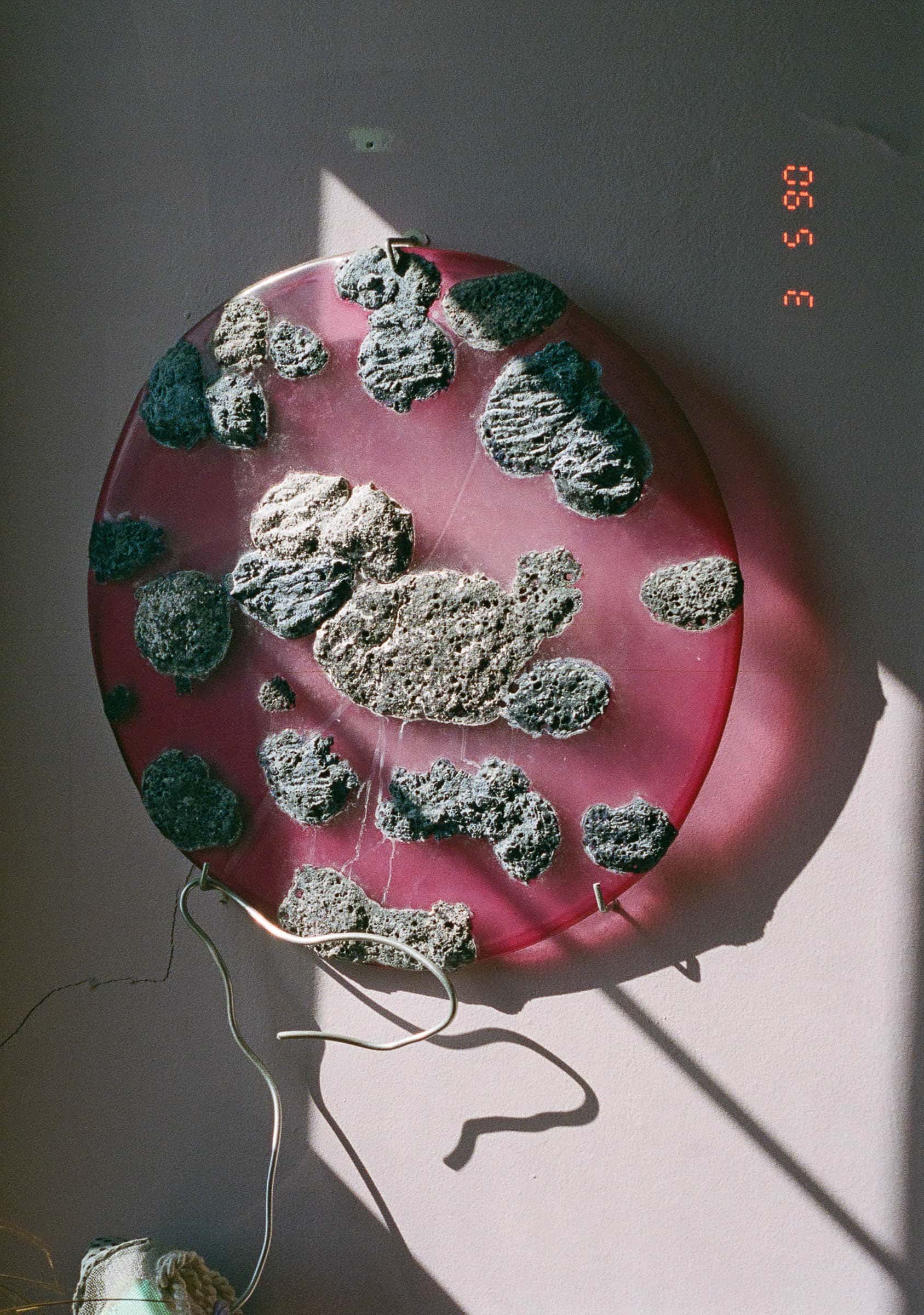

New York City: A few weeks before interviewing Misha for this piece, our mutual friend Nina Johnson invited us (and several other bright lights) to dinner in the East Village. It was Indian food. One of the spots with chilli lights hanging so low you have to stoop to make your way to a table. Conversation covered love, fixation, passion mingled with professions, boredom, expectations, and our individual modes of existence as creative individuals. Misha was the quietest person there. He wasn’t small or in the background, but rather unbothered and observant, engaged and in his own world simultaneously. He identifies as shy, which he is, but most people assume he’ll be loud, boisterous, and vocally zany because of the visual energy of his work. There is a centuries-long tradition of this type of conflation, very likely linked to our fetishism of artists and artists’ lives. But with Misha these projections seem even more prevalent. Perhaps because his work is constantly changing, and at a breakneck pace. He is one of those rare contemporary artists whose work remains as exciting now as it was 10 years ago when he set out on his own. His trajectory has been untraditional. He spent a year recalibrating on a Fulbright fellowship after graduating from Rhode Island School of Design. Afterwards he worked for a set shop building animatronics. Which was followed by a few years assisting a prop stylist, making still lifes. It was while he was assisting this stylist that his own work started to gain notice. Starting usually with a sketch, his ideas and method of creating are fully free flowing. He intentionally allows the subconscious to seep out. Misha’s work is a chicken soup for the unrepentant. There is no strategy, no rigidity. All that Misha requires of himself is honesty. The work is functional (sometimes only barely so) because that is the type of output most natural to him. No material is off limits; no colour or pattern beyond consideration. Misha is a dreamer who doesn’t remember his dreams. Someone living happily in the liminal, freely associating a reality of beauty, fun, and perversity perfectly interwoven.

close

close