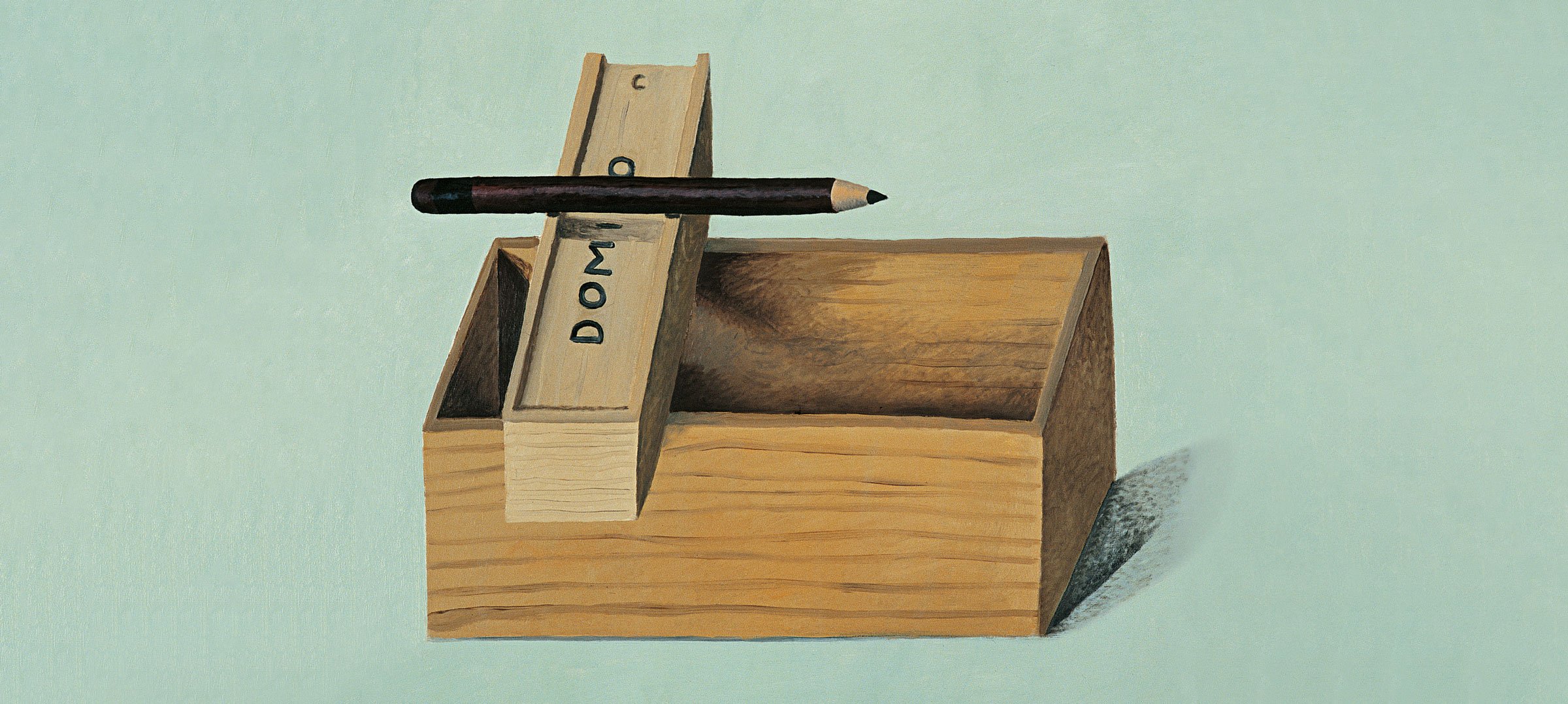

In the southernmost section of the Colonia Roma lives Michael Nyman. This neighbourhood has undergone a very profound transformation, perhaps becoming the best example of gentrification in Mexico City, but it’s still surprising to find such an unexpected character roaming a still-traditional environment, spending time amid second-hand bookstores, tortillerías, and restaurants that offer biodynamic wines and fusion meals. He combines these days with long periods in Milan, where he spends almost all the rest of his time, and increasingly sporadic periods in London, where he visits family and does the odd piece of work. His house, a building from the ‘30s meant to be the home of a large and well-off family, is gradually becoming a bookshelf for all sorts of collectables: photographic archives of several families, designer furniture, antiques, a magnificent grand piano, and books from almost any time and about any topic. Every room is an extension of his studio, and piles of documents and photographs and work-in-progress sheet music and the like can be found lying about almost everywhere. He is presently working on his first grand exhibition in Mexico City, and this may be the reason for such extreme (apparent) disorder.

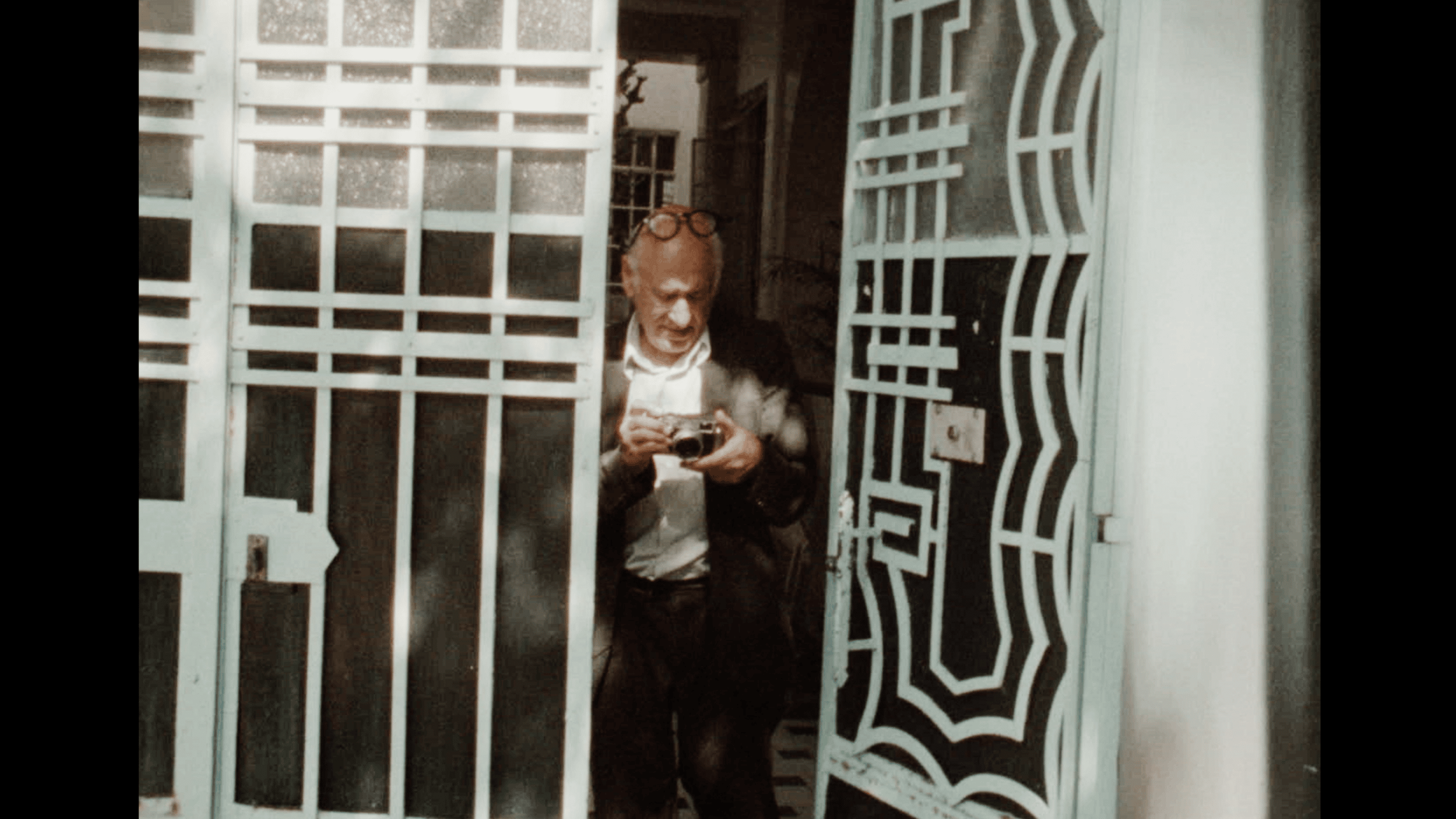

Nyman is best known for his music. Hearing his name immediately leads us to the composer of Jane Campion’s movie The Piano, or to his outstanding collaborations with Peter Greenaway. One of his most salient characteristics is that he has a solid theoretical background as an artist, not only in music, combined with a vast personal knowledge of very important artists and a depth of personal experience, which is relatively uncommon. Nyman is not only a composer but also an important music critic, who, among other things, coined the term ‘minimal music’. A lesser-known facet of his career is his work as a photographer and filmmaker. These two aspects appear to have gained greater importance in his life in recent years, and he seems determined to express them more and more. The 14 years of his life in Mexico appear to be an intense and permanent search for new experiences, both in personal and professional terms—and if this is so, it’s in deep contrast with a much more rigorous and systematic past.