Stockholm: I was in Vardzia, Georgia, when Levan Akin’s And Then We Danced came out. The narrative follows a gay dancer navigating love in Georgia, and I watched hundreds of people protesting the film in crowds that extended from a cinema in Tbilisi down Rustaveli Avenue—led by the far right and members of the Georgian Orthodox Church—on a small television with the volume turned down low while our hosts sang traditional folk songs. The film only played for three days; the army had to be called in, and police were posted in each screening room.

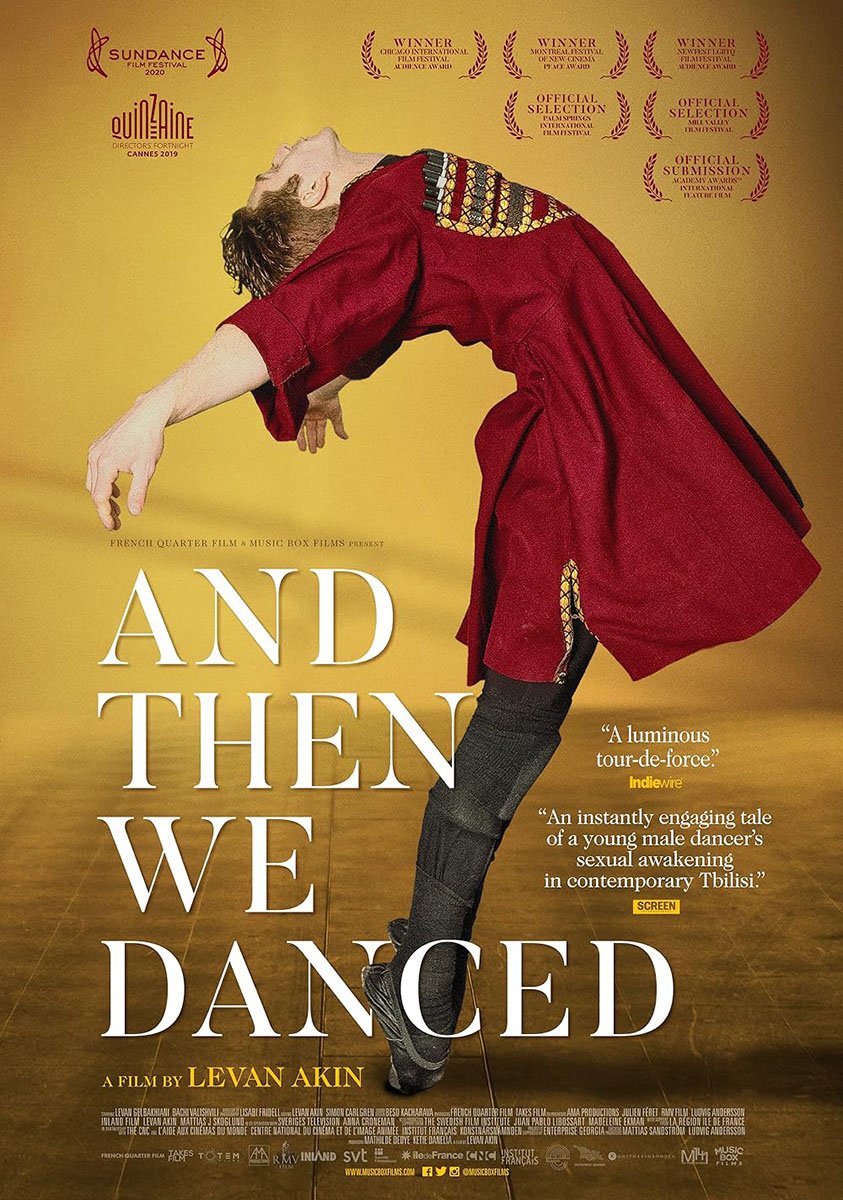

Recounting this story to Levan, the Stockholm-based, Swedish-born filmmaker of Georgian descent—whose last two films, And Then We Danced (2019), winner of 29 awards including the Gold Q-Hugo at the Chicago International Film Festival, and Crossing (2024), listed as a Critic’s Pick by the New York Times alongside festival wins in Bastia, Berlin, Guadalajara, and Sofia, bravely and urgently tell those Georgian narratives rarely, if ever, seen in traditional media—he could only nod. The protests were horrible, he confided, and although he told me several times that he felt and feels he will always be an outsider, when asked whether he could imagine a better future for queer people in Georgia, he unequivocally said yes.

Endearing and intelligent, Levan’s impact on contemporary Georgian culture cannot be underestimated. His films are raw, meaningful, and unapologetically sincere, and their stories—documenting a changing Georgia, seemingly in real time—have helped to galvanise a hugely political and passionate Georgian youth who continue fighting for inclusivity and change, even as Georgia passes new legislation restricting LGBTQ+ rights across the country.

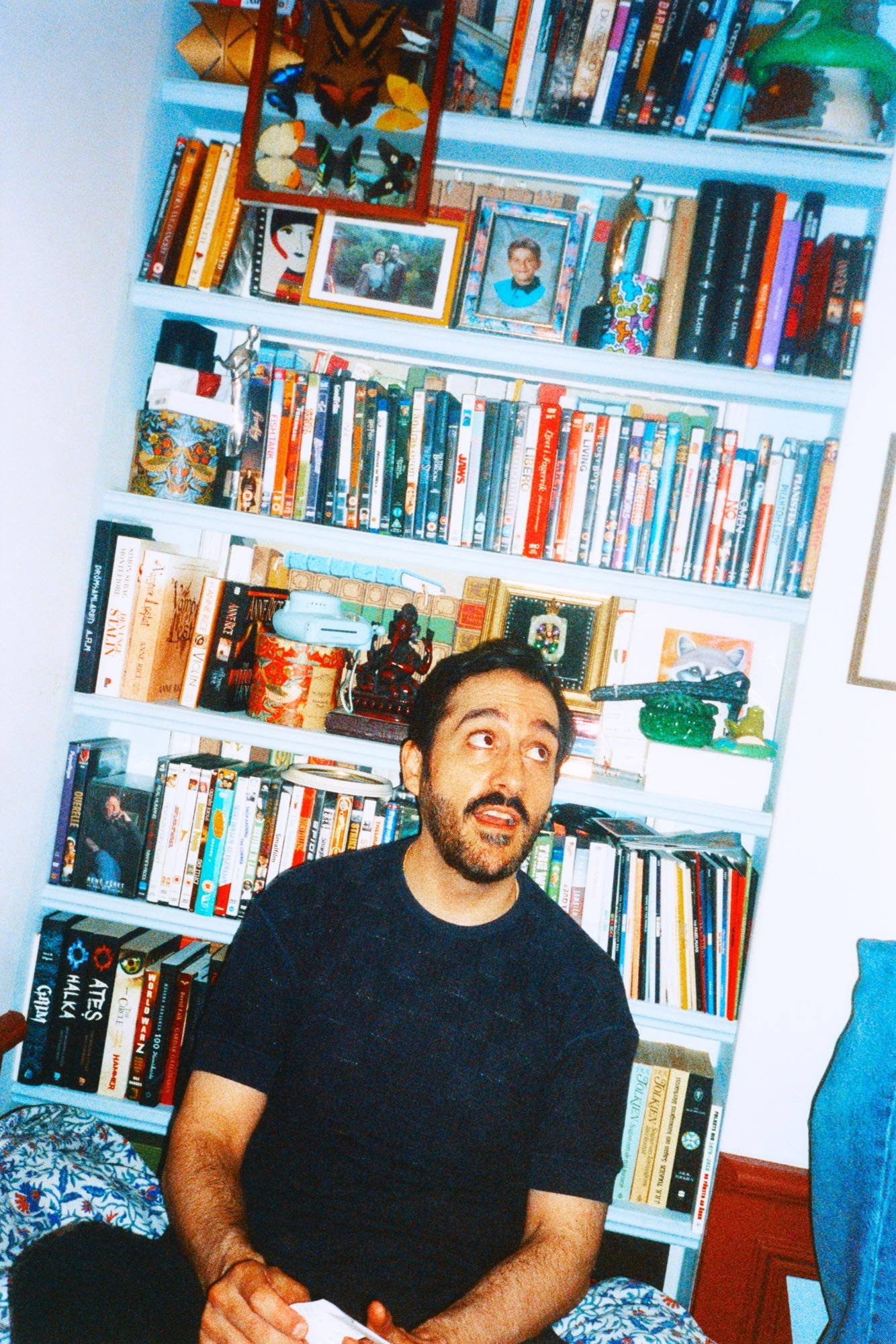

Sitting in his Stockholm apartment drinking coffee and staring at a series of tiles by Salvador Dalí hanging above his door, Levan held his cat, Olof, and communicated from a place many are too scared to sit within, which could only be called the heart. We began by talking about our distaste for small talk. It is in this spirit that our interview begins.

close

close