Copenhagen: Karl Monies’ studio is located in an old machine shop on Refshaleøen, a former industrial site in the harbour of Copenhagen, and it’s the usual place where he meets his friends and colleagues. Here, he will offer you a cigarette from the pack he keeps in his drawer while you immerse yourself in his assemblage of ceramic containers and his many books about mysticism and political revolutions. Today, however, I’m visiting Karl in Amager, an old workers’ district in Copenhagen, where a 1990 German Red Cross ambulance that he converted into a nomadic workshop distinguishes his house from the others that line this quiet residential street. Karl’s home is perfectly balanced between humble chaos and neat curation. The kids’ plastic dinosaurs live side by side with his collection of contemporary and functional art, most of which he has collected from friends and colleagues.

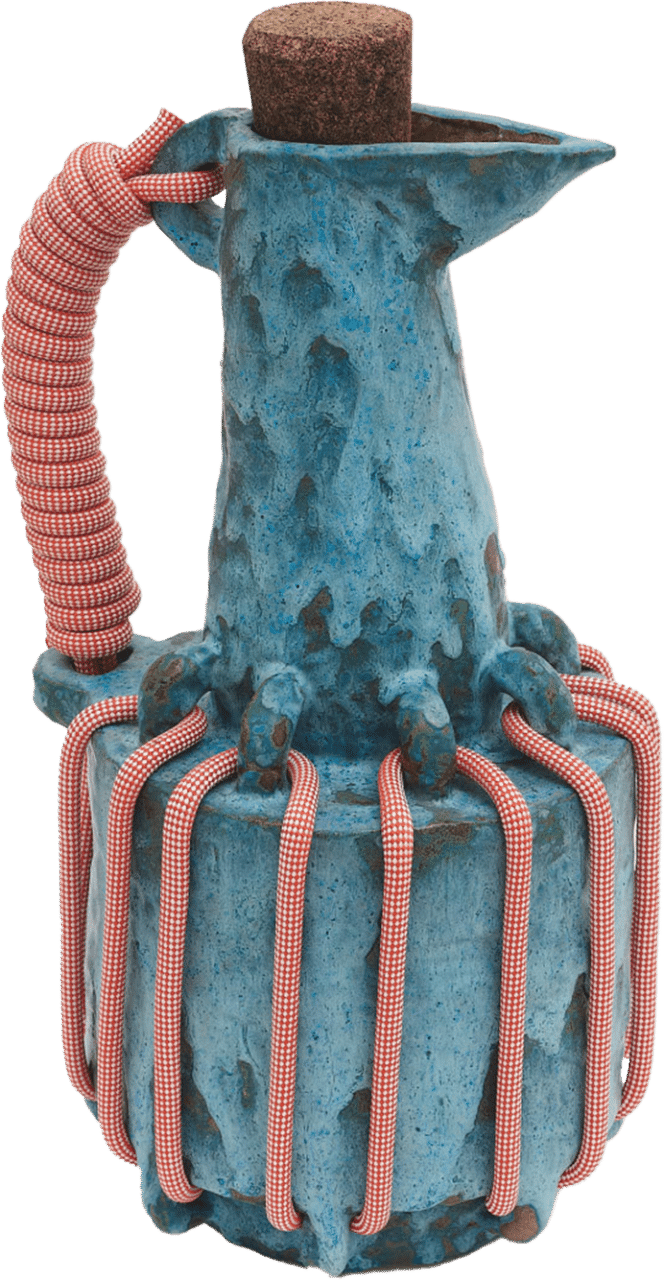

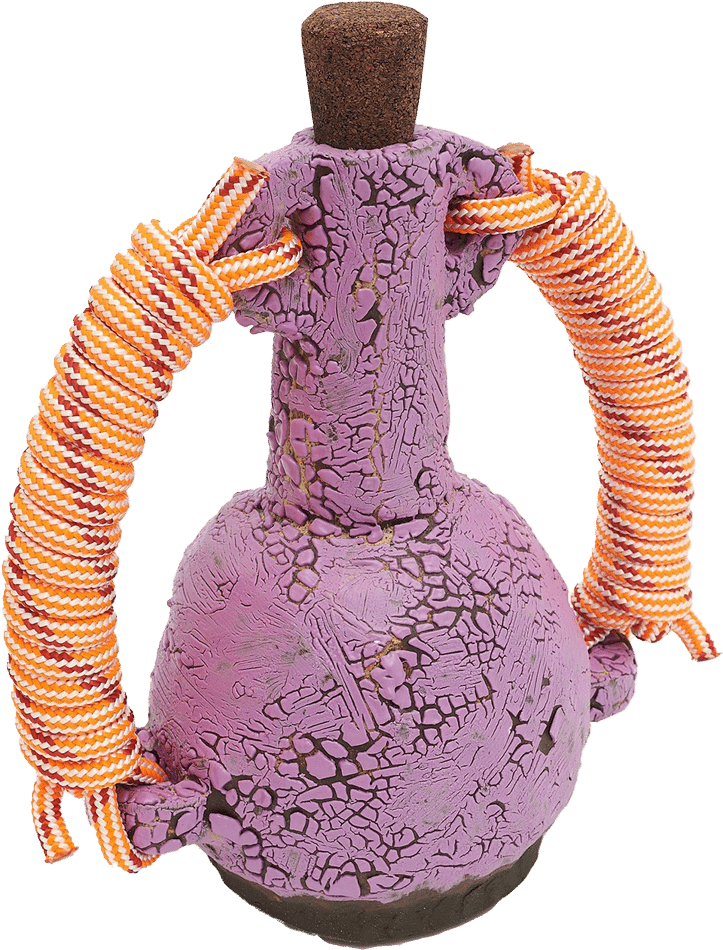

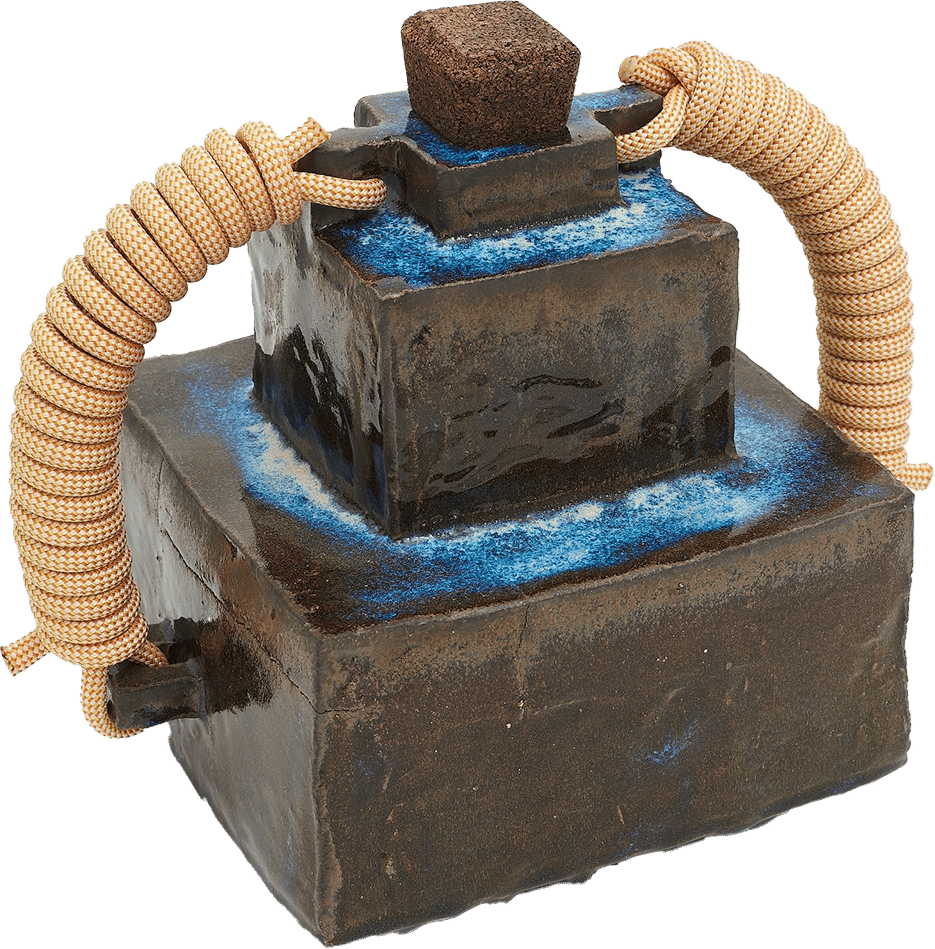

Karl is both an artist and a designer, known for his intuitively unpolished style and humble investigation into functional art and aesthetic crossovers. I met him three years ago when I was working at the art and design gallery Etage Projects in Copenhagen, and we decided to write the text for his upcoming exhibition, CAMO, together. The show engaged camouflage as a phenomenological tool to perform social belonging through various mediums and different design objects. Add to his practice the reflections of a traveller, a time traveller almost, and his work is rooted in the experiences he brings with him from his many years abroad as well as his urge to escape fixed categories.

close

close