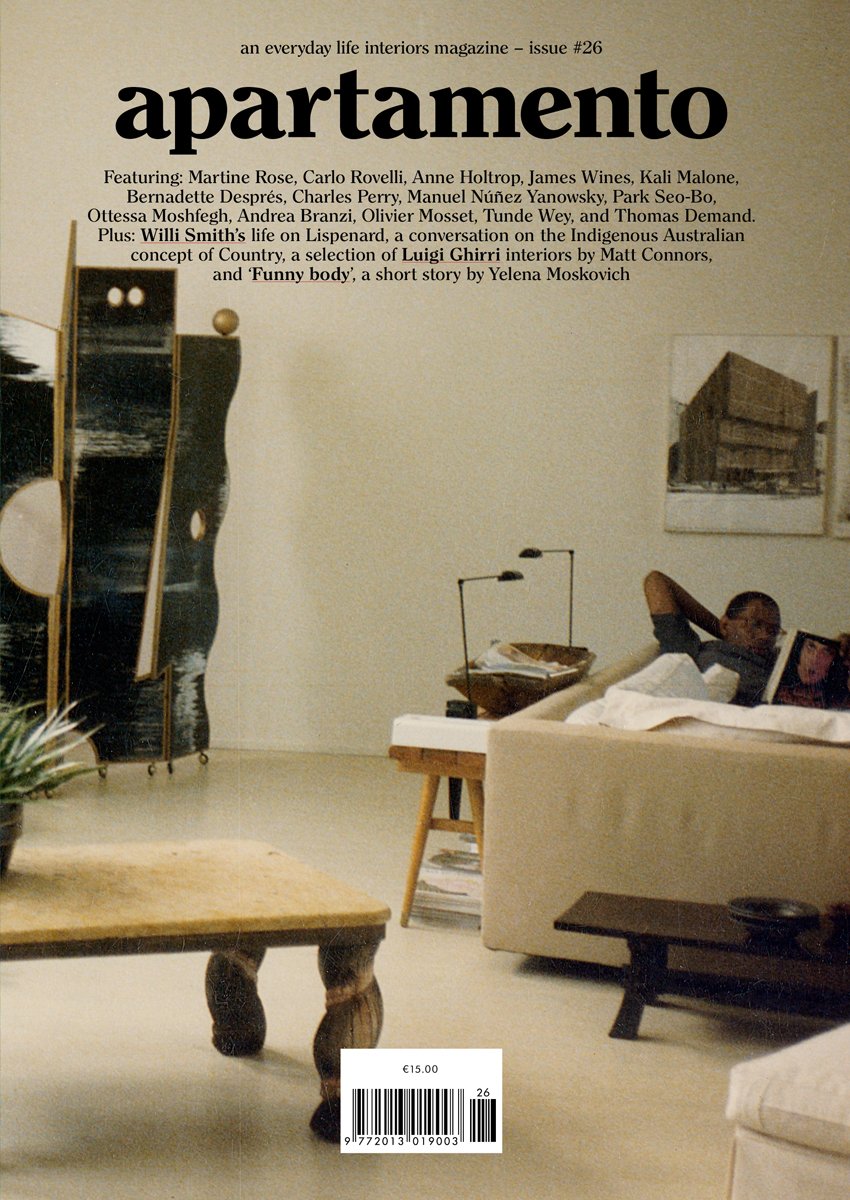

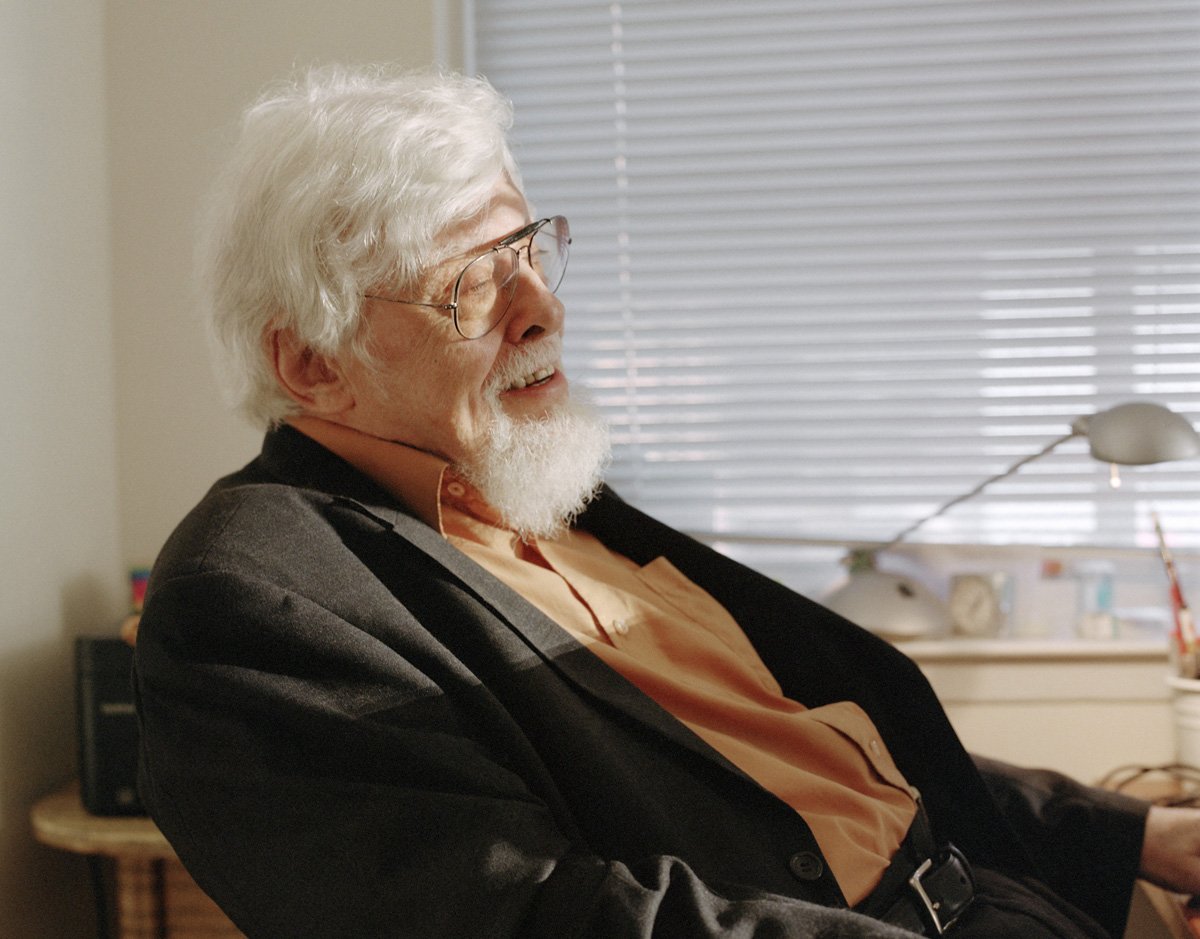

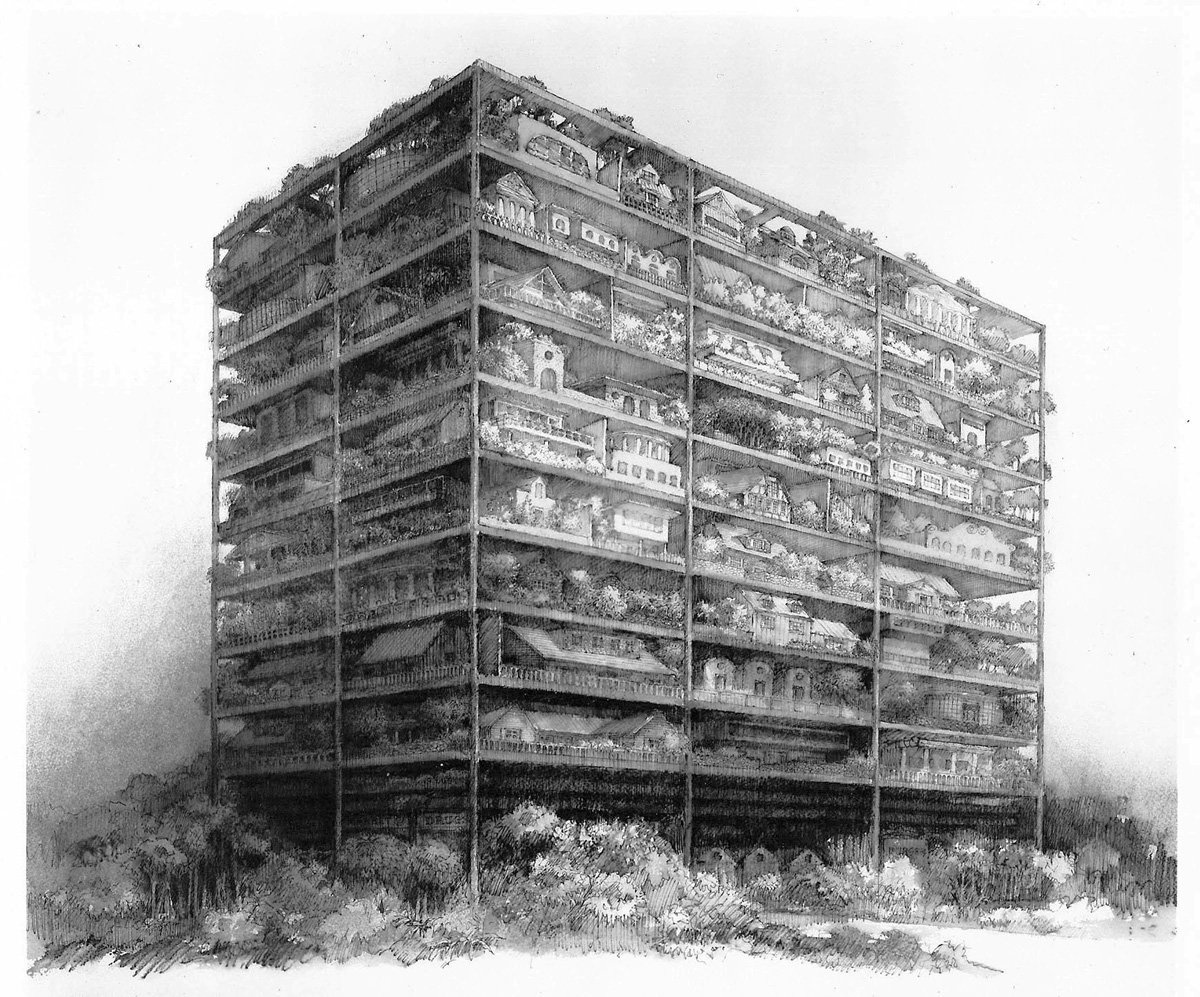

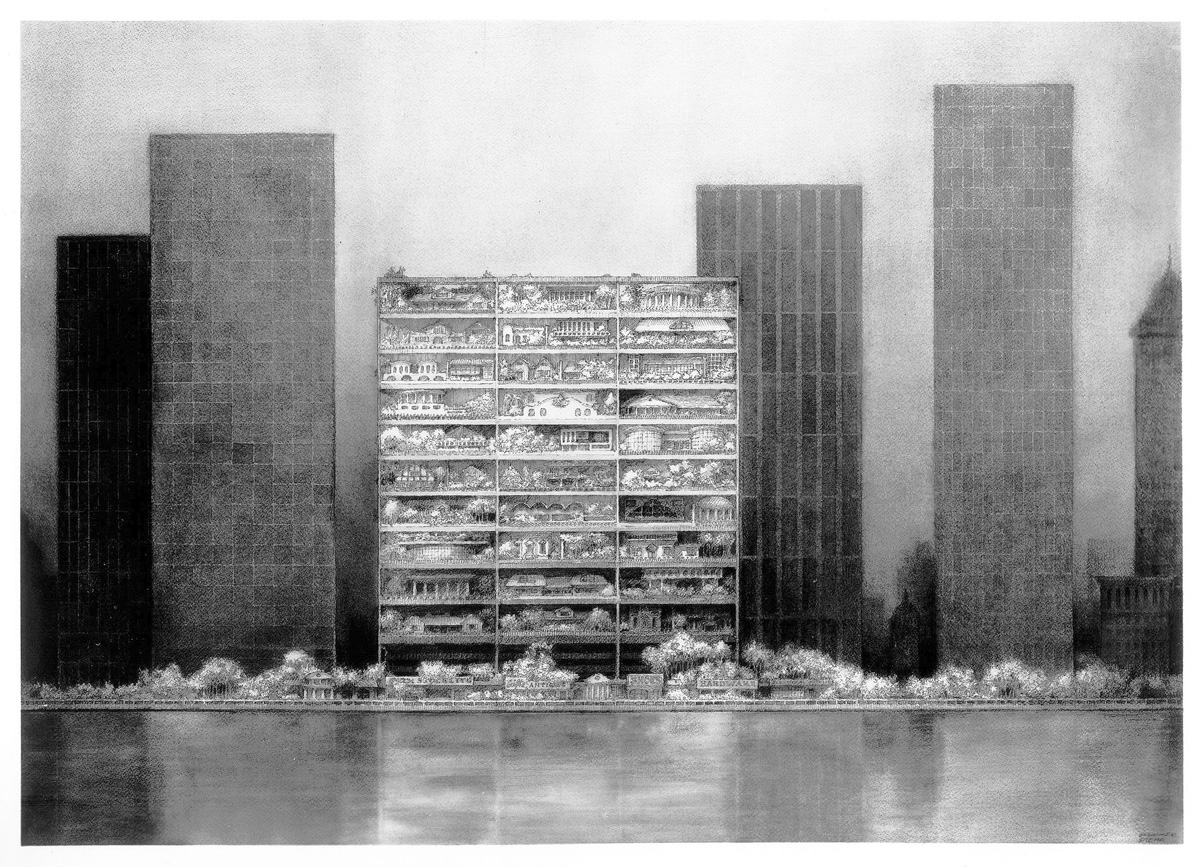

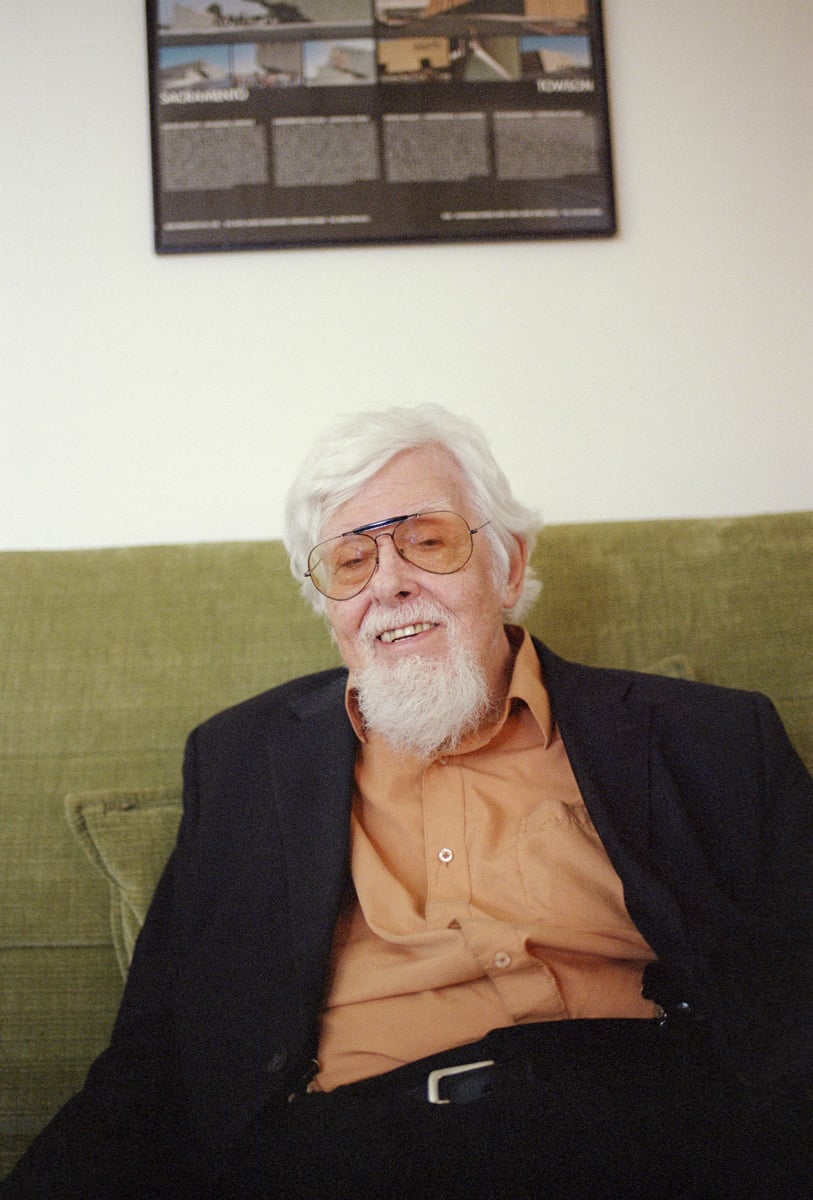

After featuring James Wines in issue #26 of Apartamento, we asked the New York-based artist/architect to elaborate on some of the themes he talked about in his interview with contributing editor Leah Singer. Wines co-founded the architecture firm SITE in 1970 and perhaps his best-known works are those he designed for BEST Products: suburban retail outlets that looked incomplete, abandoned, and destroyed, challenging the appeal of the generic sprawling shopping malls popping up across the country. His work critiques the practice of architecture, the context in which it exists, and the very means of its construction. Below, he shares some thoughts about the future of architecture in the 21st century, a period of multiple ongoing global crises.

We covered a lot of art and architecture territories in our dialogue for the hard copy of Apartamento magazine; so I will try to add some general comments on the overall cultural ambiguities we find ourselves in today. Primarily, this is a moment in architectural history when professional practice appears to be confronting its most complex and confounding challenges. The coronavirus pandemic’s impact has left the design scene in a state of unique ambivalence, where all of the qualifying rituals for past success appear to be in head-on collision with reality. As an artist/architect dedicated to conceptual, theoretical, and aesthetic priorities, the whole situation makes me feel a little like the proprietor of a pricey restaurant, with closely spaced tables, forced to operate in a world of social distancing. The urgency of my services seems questionable, to say the least. This (no end in sight) global scenario of health threats, economic peril, and political conflict has decimated all of those formerly reassuring art and design career assumptions.

Adding to these anxieties, my primary uncertainties now are based on my position as an artist who invaded architecture through the back door. For me, working in this hybrid context has always been a state of mixed blessings. Over the years, my commitment to the integrative arts has generated a roller-coaster sequence of critical controversy, professional rejection, economic instability, conceptual innovation, media attention, artistic satisfaction, and a few moments of glory along the way. In totality, my career choice has been high-risk and not recommended for anyone whose objective is job security. The main challenge, for me, has been actually practising this fusion of the arts. It meant that both clients and audience were required to share my integrative approach and feel comfortable with unconventional aesthetic relationships.

close

close