This text isn’t only about isolation; it’s about living in controlled worlds that we create for ourselves. And it is also about freedom, and how we sometimes find liberation in situations that might at a superficial glance seem restrictive.

In the very early ‘90s, when I was a young artist and had just moved to New York in the middle of a deep recession, I built a Management and Maintenance Unit for myself to live in. This was a 56-square-foot unit that basically consisted of three walls made out of a steel grid filled in with birchwood panels. The structure had built-in furniture: there was a table that could be used for cooking, eating, and working, shelves for my books and dishes, benches with storage space to put my clothes inside, a utility sink that I also took baths in, and a loft bed for sleeping. The entire unit fit neatly within the 10 x 10 foot room that I was living in at the time. When I was living in this unit, I used to think about how liberation and oppression were inextricably connected—how confinement could feel like a certain kind of freedom, and how having too many choices often became oppressive. My home had shrunk to a footprint about a third of the size of a regular bedroom, but it felt empowering, not restrictive. I started to wear a uniform to solve the problem of limited closet space, and the uniform also served me well.

When I look back at that time, I think about how this structure made me feel exempt from the dogma of growth and accumulation that seeps into our lives as we gradually settle into the patterns of contemporary capitalist culture. A few years later I decided to quite literally move onto a deserted island—specifically a 54-ton habitable concrete island which I built in the Øresund, the body of water between Sweden and Denmark. The impulse to build the island was actually inspired by the culture of suburban California where I had grown up: a place that had been rural and wild in my childhood and was now being quickly covered in cheaply built housing tracts. Back then I used to think about what would happen when all of the land had been developed. I fantasised about making islands for people to live on that could function as their vehicle, land, and dwelling. I thought that once all of the land in California had been built up, people could establish neighbourhoods of these islands, marching off in neat rows from the coastline of California.

The prototype of my island took two years to build, and when it was finished I went to live on it for a summer. The island had a hill in the middle, and, inside that, there was a two-room interior that opened out onto two outdoor patios, and between those was a dirt-filled growing area with a small tree and some plants. I had wound up making the island in Scandinavia because there were funding opportunities in a culture that prioritised culture and experimentation more than my own. At first, I supposed that I would be alone on the island—something that greatly appealed to my introvert nature. But instead, during the summer that I was living on it, the waters were filled with private watercraft circling my island, manned by people asking questions about what I was doing in languages that I couldn’t answer. At one point two guys onshore stripped down to their underwear and swam out to the island planning to hoist themselves onboard. This was clearly not the vessel of solitude that I had planned it to be.

Finally, my fantasy about really truly being alone did come true for a project that I set up in a basement studio in Berlin, where I shut myself off for a week from all sources of external time (sound, light, clocks, phone, and the time settings on my computer and email programs). I had never really stopped thinking about the contradictory nature of freedom, and I wanted to take on the invisible structure of (measured) time—something that I think controls us even more than any physical structure. What I found through this experience was that living without time was both exhilarating and harrowing. It was like being on a drug, but without knowing ahead of time what the effects would be. Before I started my ‘time trial’ I imagined that living without time would be relaxing. I had been preparing for a fairly large museum show, working all the time and feeling very stressed out and exhausted. But what I found was that without the clock I worked even more. I literally didn’t know when to stop working. I concluded that the controlled structure of time is there to tell us when to rest as much as when to work.

Lately, everyday life for all of America (and the whole world) is starting to feel like the same kind of petri dish that I’ve often constructed for my personal practice. I’m not sure how everyone else is doing, but I’m personally having some moments of déjà vu. Not so much in terms of the isolation or deprivation, but more about the insanely strong human impulse to fill every possible void, similar to what happened to me when I was in that basement studio in Berlin. Back then my busyness was entirely self-created, but now it’s something that I see us generating collectively. In our culture I think that anxiety presents itself as ‘chatter’. And this chatter, right now, is coming specifically in the form of ‘content’ (basically what I’m writing right now).

I’ve been asking myself a lot of questions lately. For instance, I wonder how much information our minds can actually hold? I did some research and found out that in 2009 Roger Bohn conducted a study at the University of California, San Diego, to measure how much information is absorbed daily by American consumers. He said that we are inundated every day with the equivalent amount of 34 gigabytes of information—enough to overload a laptop (at least at that time) within a week. I also wonder if this compulsive drive for productivity is the primary DNA of capitalism? And finally, what is the difference between creativity and productivity? The same researchers at UCSD who calculated how much information our brains take in also said that the main effect of all of this information is that it hampers our ability to focus and inhibits reflection and deeper thinking. Most of the information that we take in is superficial, and what we are sacrificing is deep thinking and creativity.

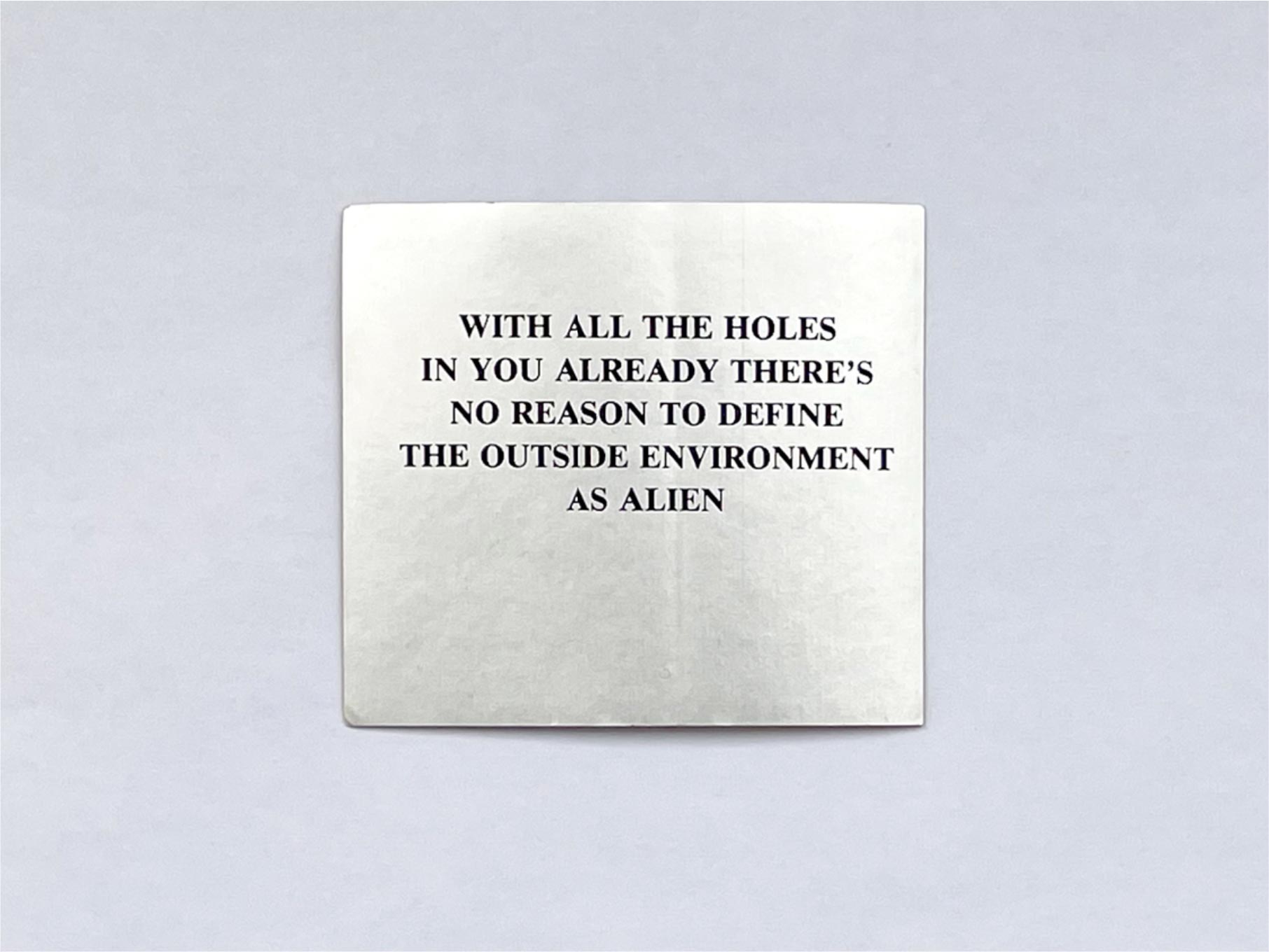

Throughout the years, and often in response to the experiments that I described above, I’ve collected small principles called ‘these things I know for sure’. Lately I keep coming back to principle number 12: ‘Ideas seem to gestate best in a void—when that void is filled, it is more difficult to access them. In our consumption-driven society, almost all voids are filled, blocking moments of greater clarity and creativity. Things that block voids are called “avoids”’. Is it possible that productivity is the antithesis of creativity? If productivity is the attempt to ‘fill’ something, I would say that creativity comes out of the void.

The living experiments that I’ve created within my own practice, as well as the current impositions that we are collectively experiencing while sheltering in place, both result in what could best be described as a sense of unease, fear, or nervousness that is simultaneously paired with an odd euphoria at seeing everything we once believed to be solid coming apart. It’s an unmooring that ultimately offers up new opportunities to confront the world as it stands before us.

close

close