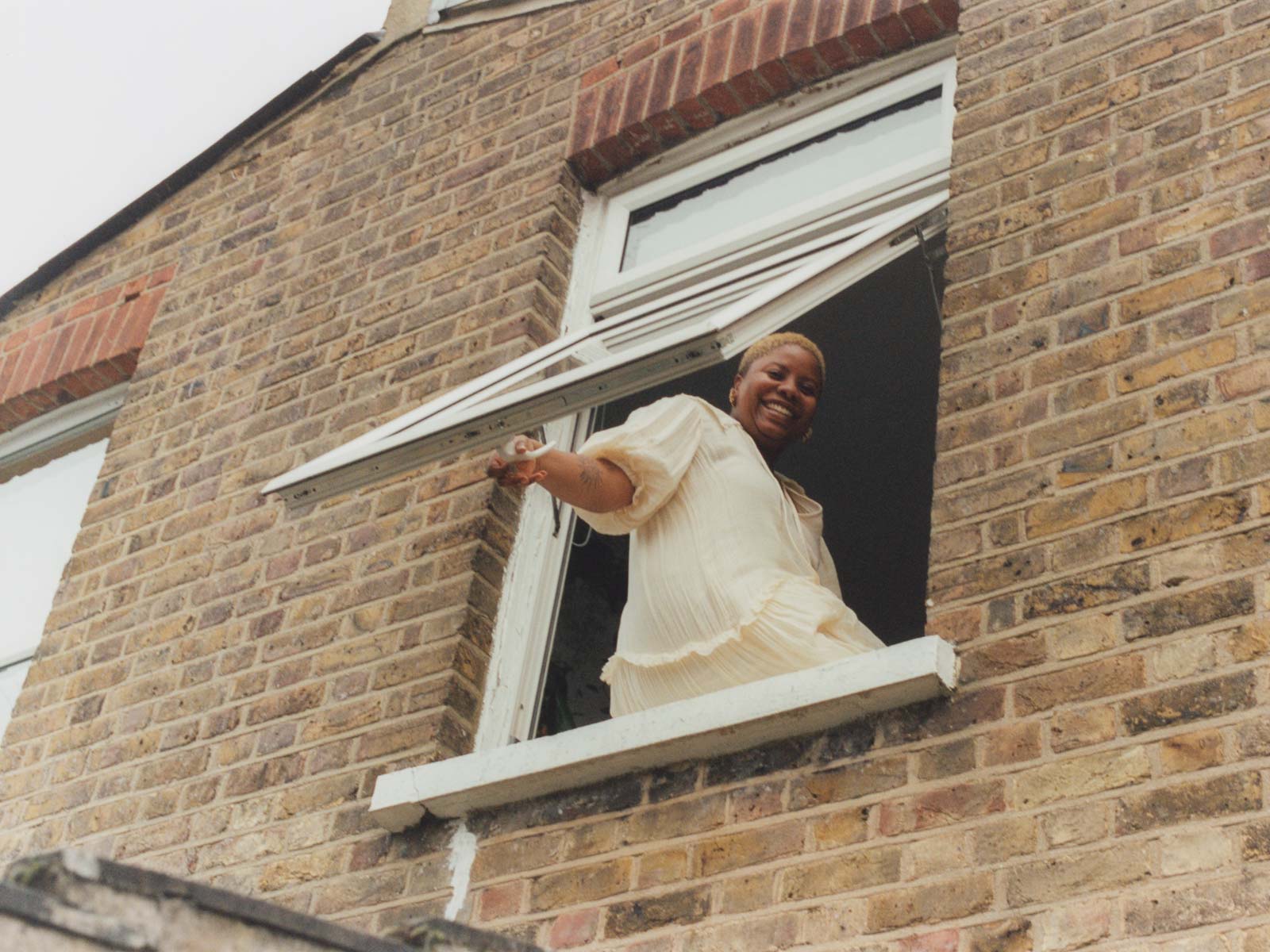

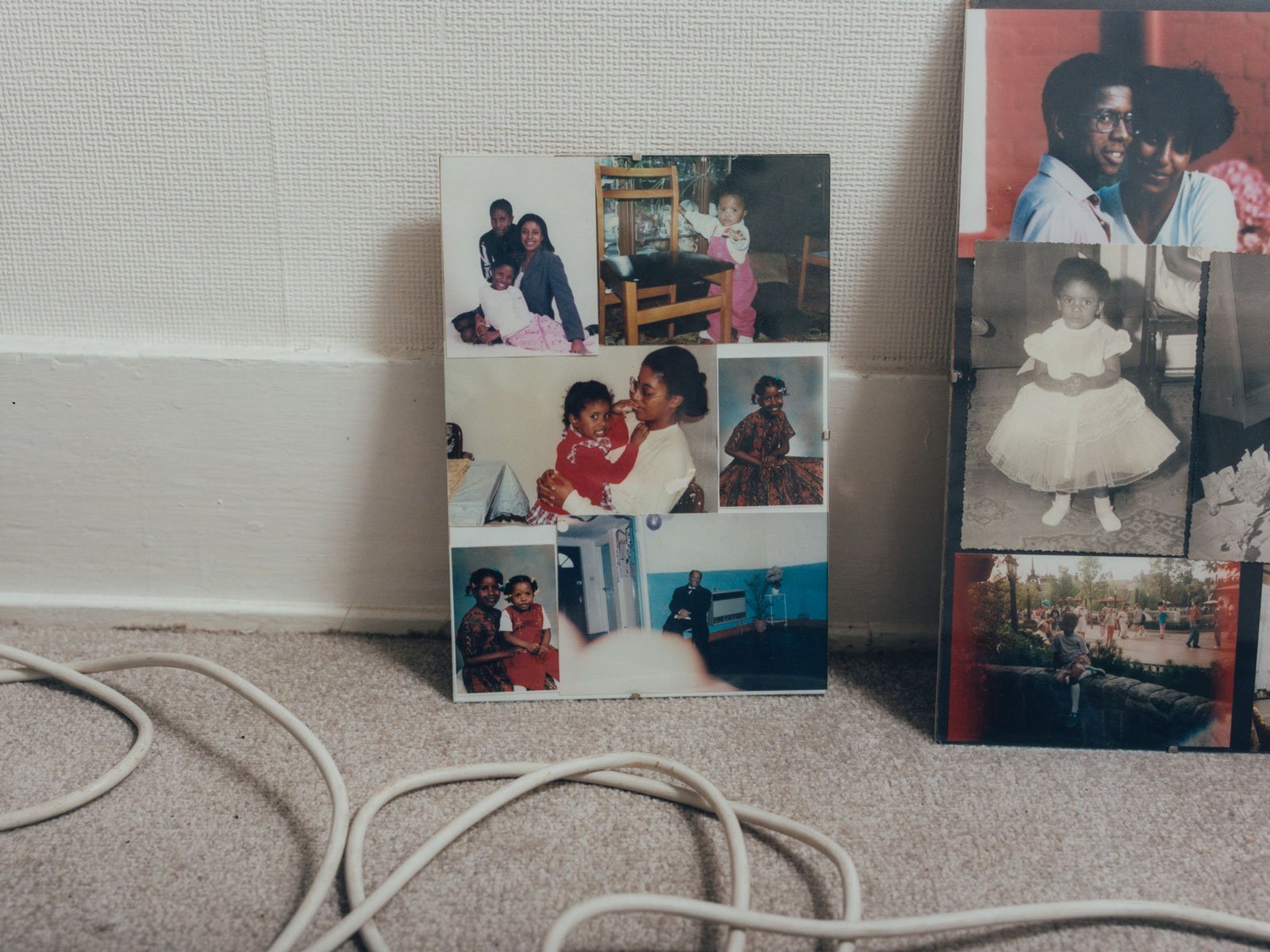

London: For a word that’s bandied around so liberally, it’s fascinating how loose the definition of ‘sustainability’ is. At its most fundamental, it refers to ‘the quality of being able to continue over a period of time’ (or so says the Cambridge dictionary). Today it’s used and abused most readily in connection with the climate crisis: applied to reusable water bottles, or recycled-cotton jeans, and slotted neatly, if somewhat ineffectually, into the boardroom-born marketing campaign concepts that paper our billboards. For Georgina Johnson, the term ‘sustainability’ doesn’t do the work required of it anymore. She’s more interested in ‘repair and regeneration’ when it comes to environmentalism, but also the economy and social justice. These are the ideas she takes up in her work—a multi-disciplinary practice which straddles writing, publishing, curation, filmmaking, production, art, and design. After graduating with a degree in Fashion Design from London College of Fashion and a spell working for couture brands, she launched the Laundry Arts, a platform which would allow her to put down one title and pick up dozens of others. In 2020 as ‘the world exploded’, with the pandemic digging its heels in and the Black Lives Matter movement reaching a global stage, she launched The Slow Grind: Finding Our Way Back to Creative Balance, a collection of essays, think pieces, and conversations by figures across the cultural and creative industries (myself included). This collection takes up her ideas about environmentalism, social justice, and mental health, asking questions and attempting to answer some, too. It’s just been reprinted for a second run. The time that elapsed between print runs wasn’t uneventful for Georgina, who faced a crippling mental health crisis, three weeks in a mental health hospital, and a life-changing diagnosis, along with the struggles faced by the rest of the world. 2021 has seen her recovering, reframing, learning, and growing. And grinding! But slowly, now—producing a podcast, a new book, and plenty more besides. We sat down in her calm, cosy living room in South London, just a little less south than the town she grew up in, surrounded by well-tended plants, and one curious cat.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

close

close