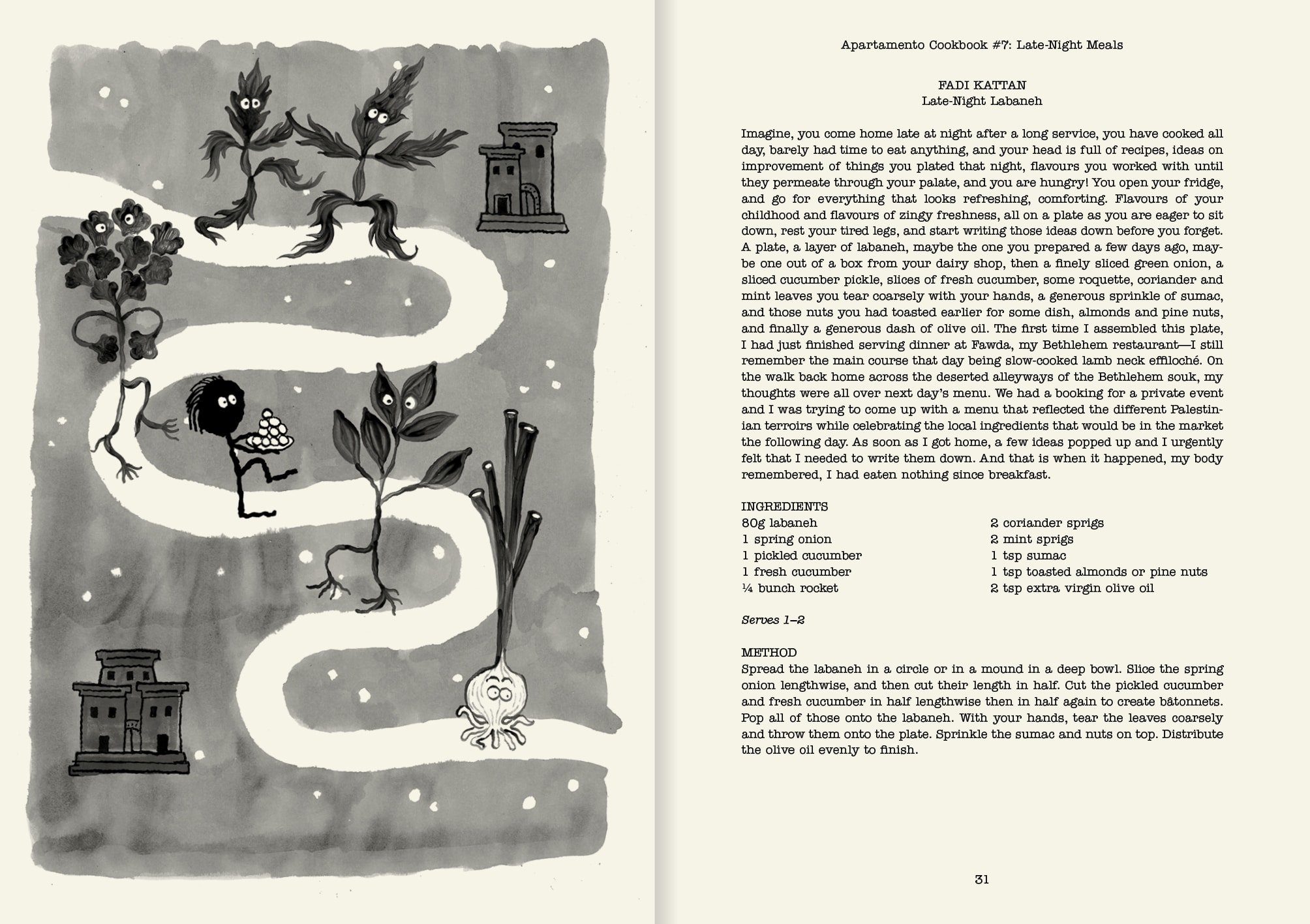

Read an original recipe for Late-Night Labaneh by chef Fadi Kattan, featured in Apartamento Cookbook #7: Late-Night Meals.

London/Bethlehem: A delicious meal is an exchange, an articulation of the care and attention paid by the person who made it—and, before them, by those who have grown the produce needed to assemble each dish. In the company of others, another layer of exchange is added—between family and friends across the table. A shared meal provides rhythmic comfort and a moment of bonding. These layers of exchange imbue food with cultural significance and invest it with a capacity to communicate. A restaurant, then, can be about so much more than just eating well.

I spoke with Franco-Palestinian chef Fadi Kattan in West London soon after his return from Palestine, where he was photographed at his home for this magazine. We met at Akub, his new restaurant and the highly anticipated follow-up to Fawda, Kattan’s inaugural restaurant in Bethlehem, which he opened in 2016. It was clear that his passion for cooking comes from a deep understanding of how food connects people with tradition and with the natural world—and how culture is intricately bound with politics and the environment.

close

close