Restaurateur, cook, and author Cynthia Shanmugalingam greets me at her front door, which opens to one of Borough Market’s only slightly more tucked away thoroughfares. Her home sits atop one of the city’s best-loved food shops, which she admits is both a blessing and a problem, emphasis on the former.

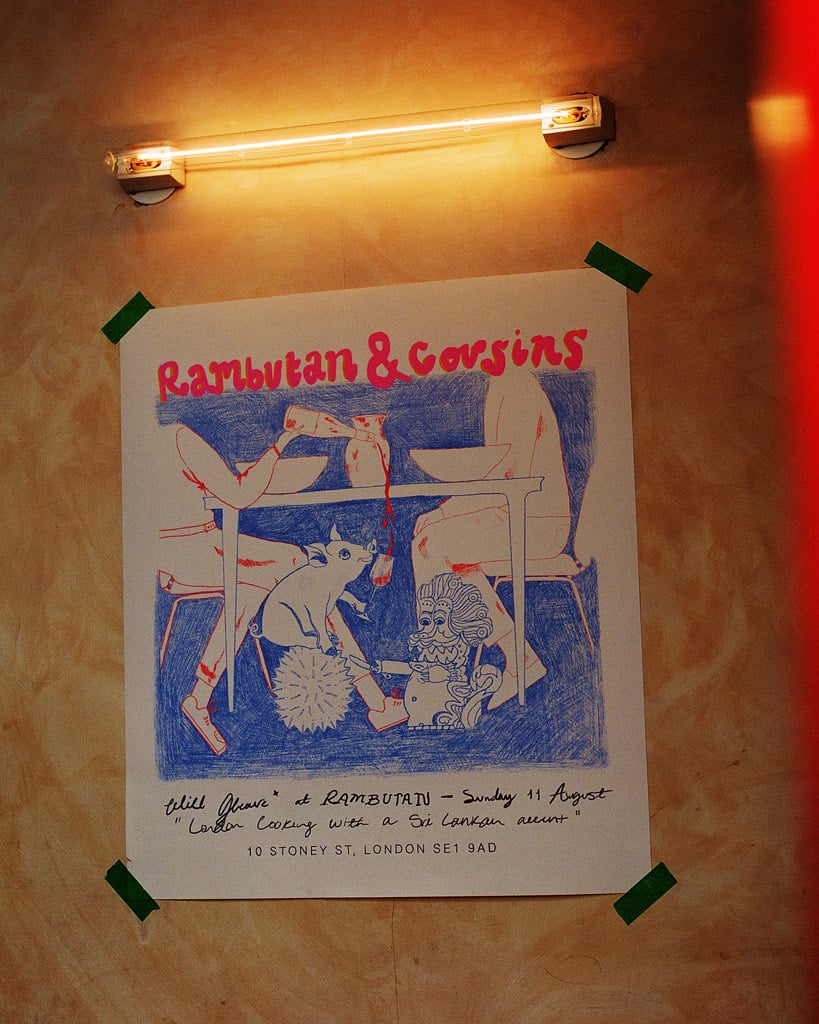

Living in one of the city’s largest and oldest food markets certainly has its perks, especially when your restaurant is around the corner. Shanmugalingam, whose Sri Lankan restaurant, Rambutan, sits a minute’s walk away, likens her life to the scene in Beauty and the Beast where the book-loving protagonist, Belle, waltzes through her local market, greeting vendors left and right.

‘My step count’s gone down to like 10’, she laughs. ‘I didn’t think this would happen to me in my 40s, where I live in central and do this, it’s a surprising change’.

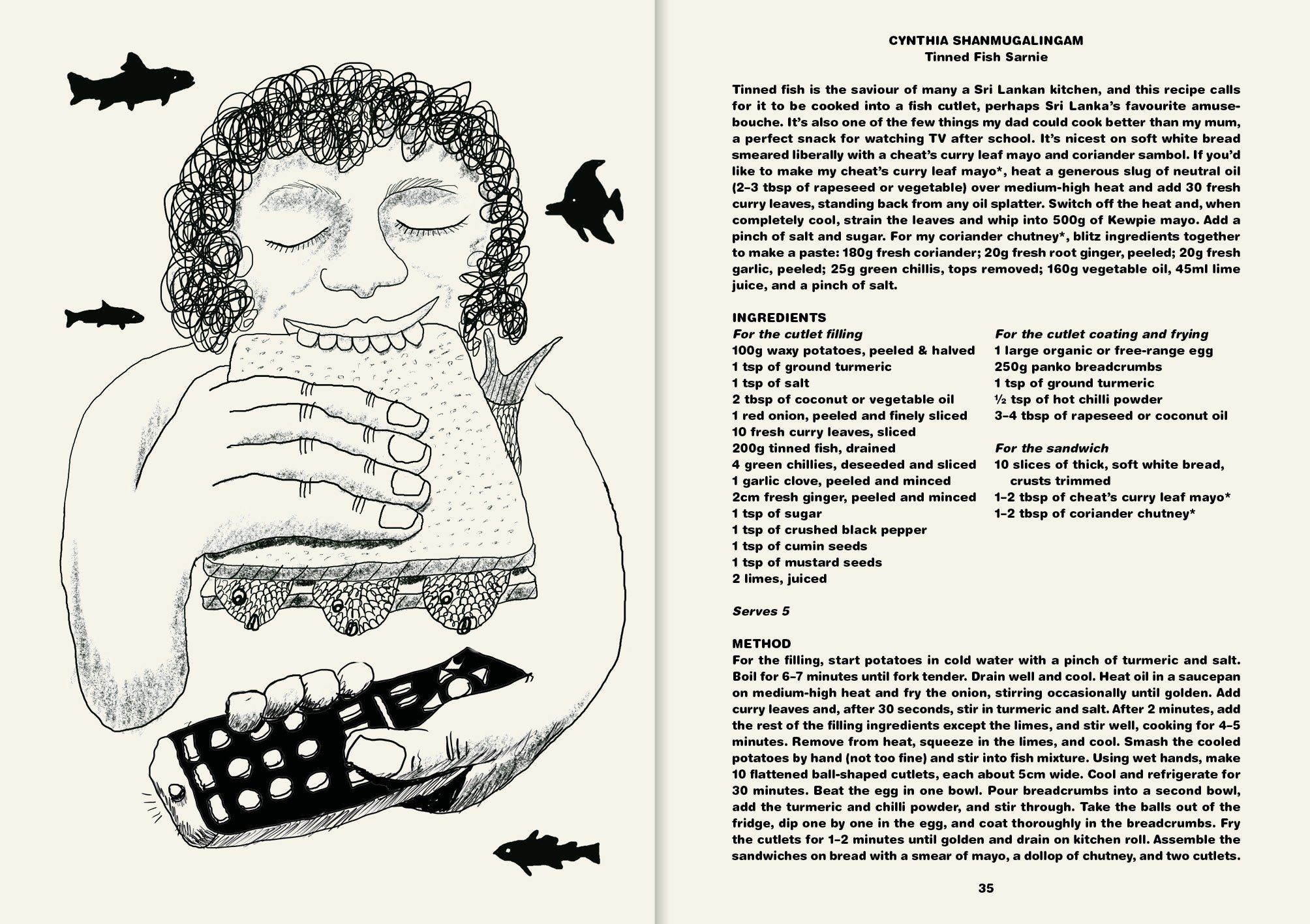

The fairytale set-up is the work of Borough Market itself, which operates as a charitable trust to hold property and preserve the area as a community hub. Traders get right of first refusal for flats in the vicinity; Shanmugalingam moved in before Rambutan opened in March 2023, and when building delays hit, her home became her team’s de facto HQ and the site of a pre-opening boot camp of sorts. ‘We ended up developing the menu in my kitchen, and all the dishes were finalised here. We couldn’t have built the restaurant otherwise’.

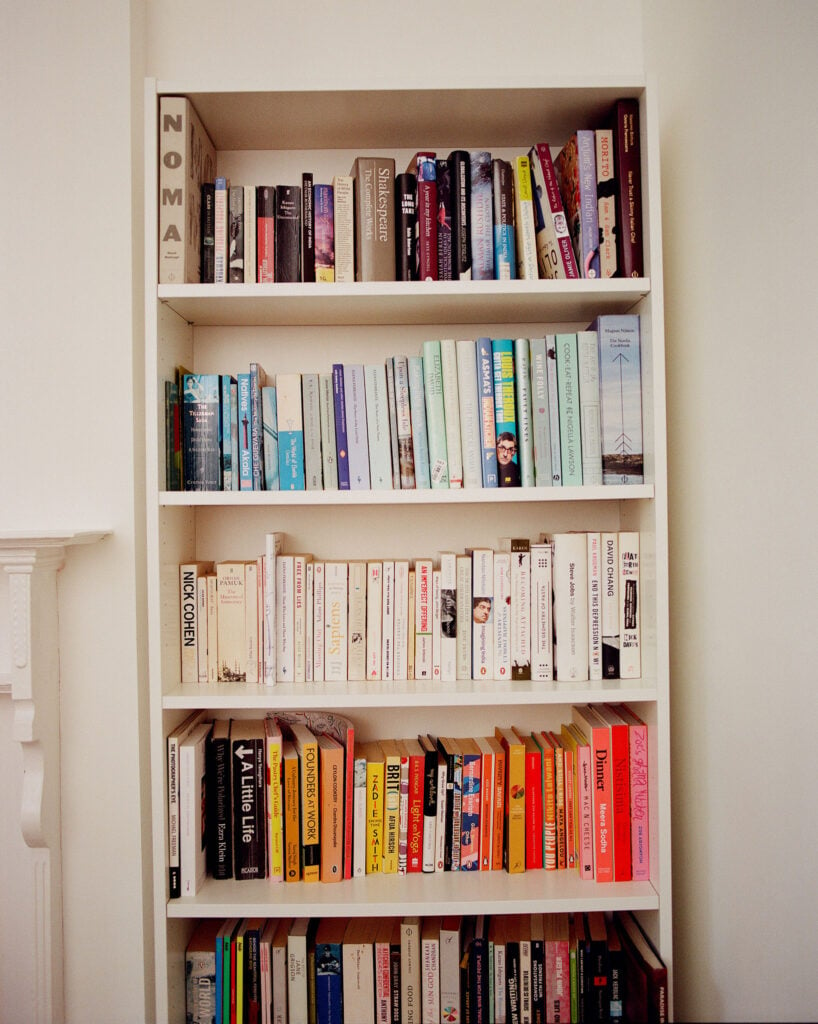

While she’s certainly had her hands full with the restaurant and her celebrated book of the same name, Shanmugalingam and her husband, Joe, also haven’t had to make many changes to their light-flooded home, which circles its rooms around a white stairwell. We enjoy the bulk of our conversation in the carpeted living room, framed by colourful sofas and a bookshelf populated by cookbooks, though she zips in and out to show me her kitchen (appropriately kitted out with top-of-the-range Gaggenau cooking equipment) and well-labelled pantry, which contains the ancient grains she’s brought back from Sri Lanka (including her current obsession: millet).

close

close