New York City: Am I about to draw links between Camille Henrot and rat poison? Yes, yes, I am, but hear me out. I’m staying in Henrot’s apartment on the Upper West Side of New York, 12 floors up but with an elevator, so I’m relieved. One bedroom explodes in blood-red paint, and other walls expose a washed-out lime that only an artist could pull off. I have Schoggi, the rescue dog with debilitating golden exuberance, for company, and firecracker walks along the Hudson River parkside become our sweet daylight bond. Racing in my direction is Erin, a man experiencing homelessness who sleeps in this park, shouting for me to get away from a green fence. Now, I’m not exactly obedient (nor is Schoggi), but it all feels a little urgent, so I oblige. Erin informs me there’s rat poison along this fence, despite it being illegal, which could be lethal for a small dog. Knowing the dog’s intense curiosity, I examine Schoggi’s every move, filled with meticulous uncertainty and maverick schisms that threaten to fracture my world at any moment. Henrot’s work is similarly dynamic. Iconoclastic, intense, and gestural, it calls to mind all the languages of the Situationists, breaking in to disrupt what I think I know about the world.

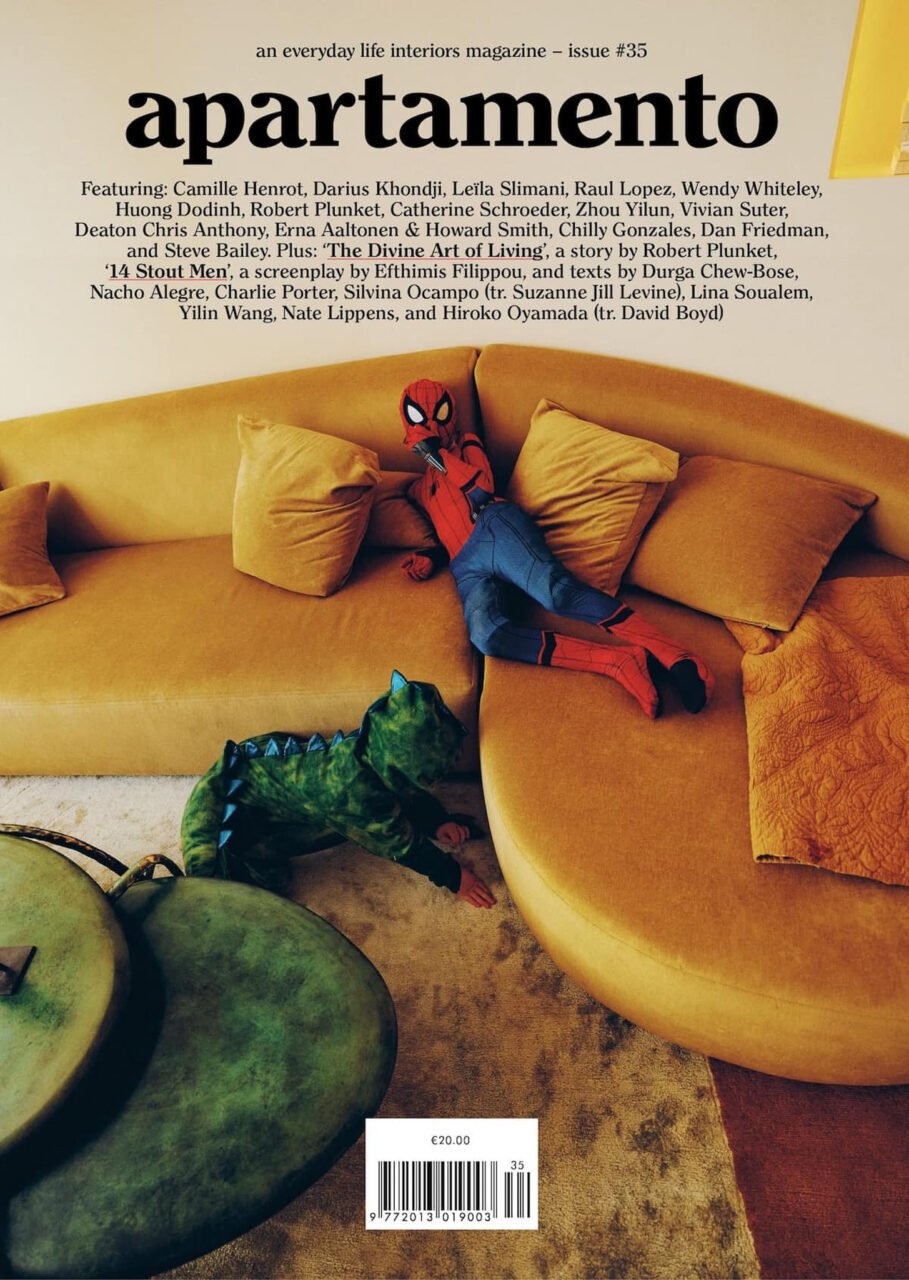

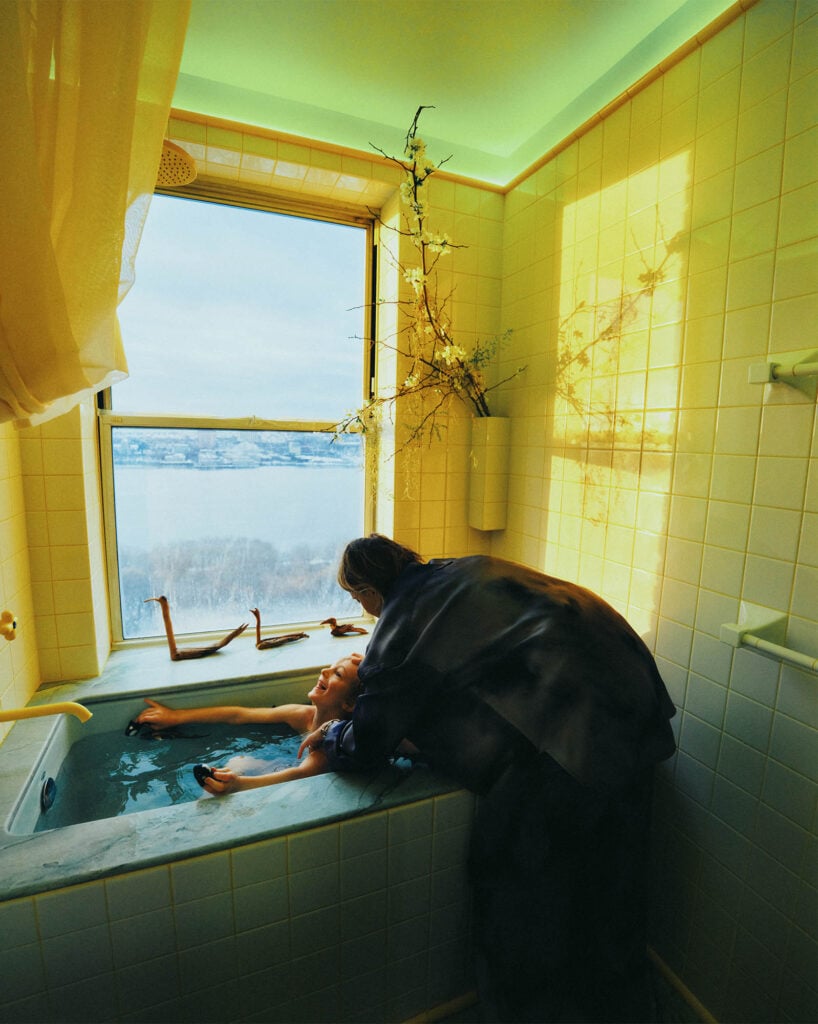

Henrot’s domestic world is soundtracked by her husband, Mauro Hertig, an acclaimed Swiss composer with a voice hovering somewhere between Nick Cave and avant-garde musician Scott Walker. Even Mauro’s half-assed humming while making chia pudding for breakfast is a revelation. Bird calling to his kids, Iddu and Sol, in deep-throated warble, they fly to the kitchen in matching clothes sets, chirping and trilling about the day ahead, epigenetics doing a gorgeous deep dive into both their little chords. Iddu and Sol’s sing-songy vocals soar effortlessly between French, English, and Swiss-German, reminding me of all the life plots they’ve yet to forge as they spread their wings over our exquisite yet flailing earth. In her upcoming art film, In the Veins, Henrot paints confrontational narratives illustrating the venomous story of our spectacularly sick planet, the same one her little birds will inherit. (Schoggi was fine, if you cared.)

close

close