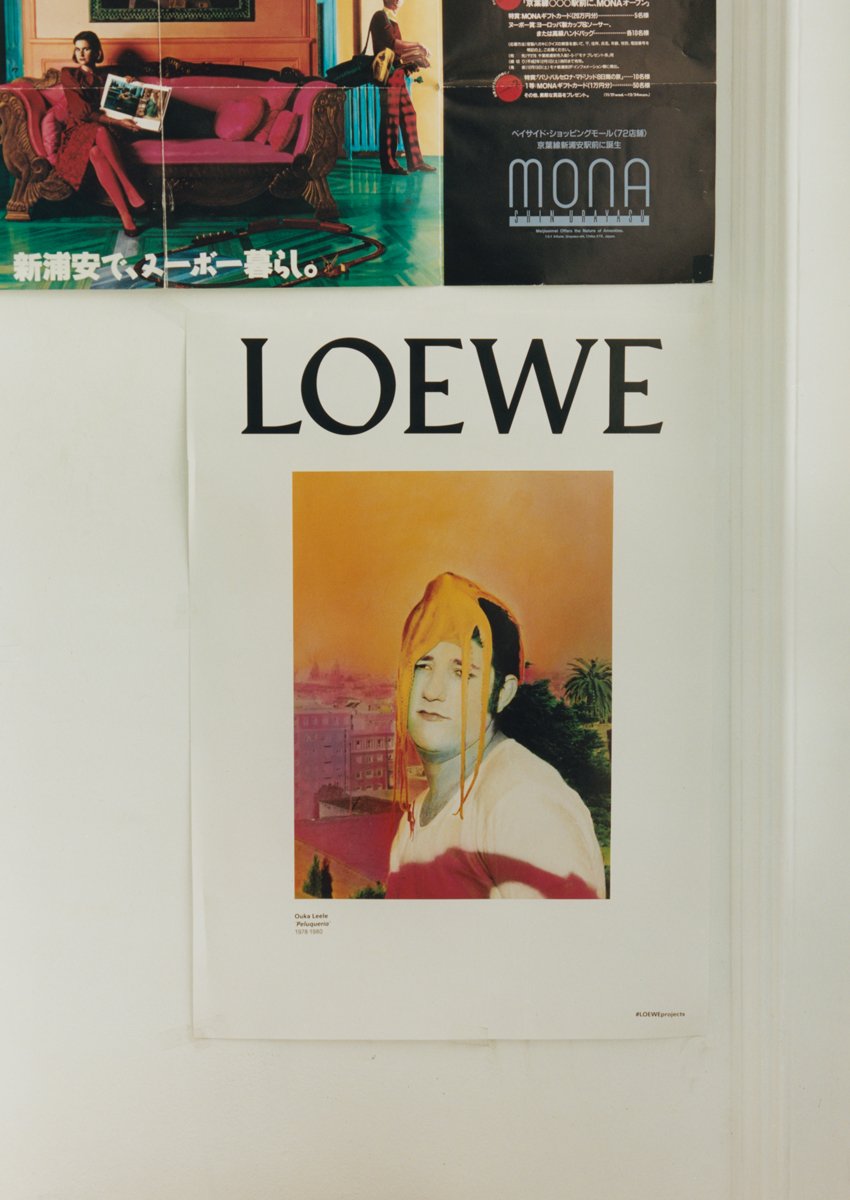

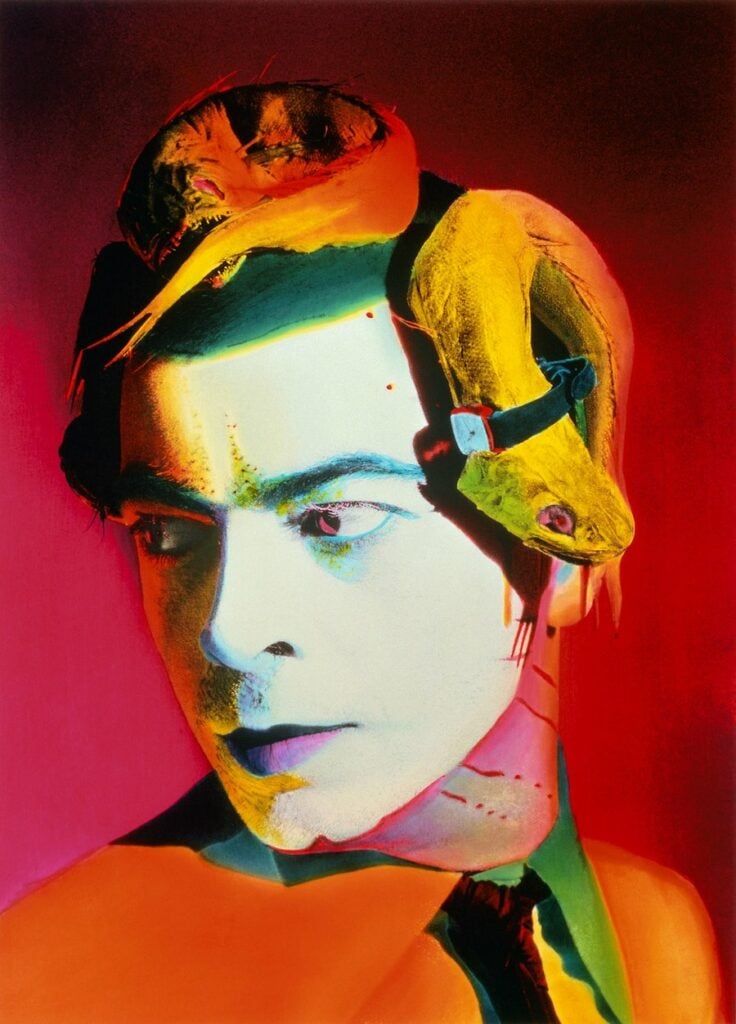

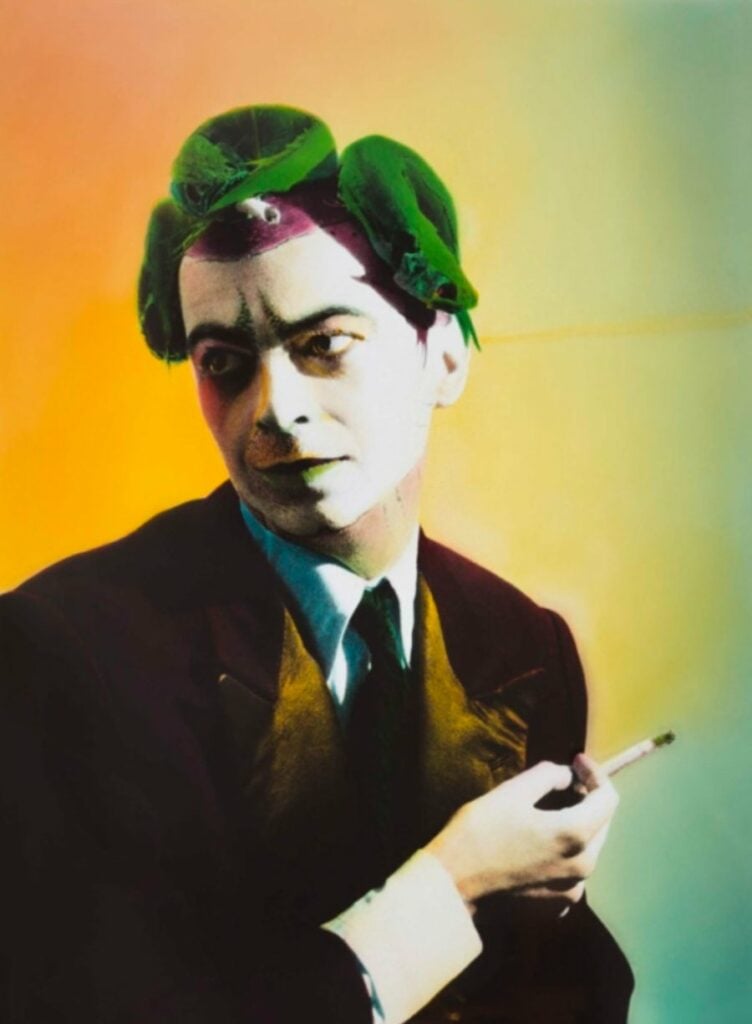

There’s a certain period of Spanish cultural history where the name Ouka Leele isn’t just inescapable but intrinsic to the creation of a certain sense of artistic freedom and identity. When the cloud of Franco’s regime started to dissipate in the mid ‘70s, the counterculture movement known as La Movida Madrileña was doing its best to break the cultural milieu wide open with its experiments in art, music, fashion, sexual and gender norms, and any other conceivable form of expression. Ouka Leele, who was just starting out on her photography studies at the time, became one of the few to capture the scene from the inside, creating a technique that’s instantly recognisable today, as she painted over her surreal, theatrical photo portraits in lurid, saturated colours.

But all this is for context. As I prepared for our conversation, I took a look back through the work of Bárbara Allende Gil de Biedma, Ouka Leele’s real name, and realised instead that I was most looking forward to learning first-hand how the past months have been for the artist. Has she worked more or differently? Was she alone? How has her creative thinking evolved in the city where she’s produced her main body of work, one that is so linked to place? I cautiously tried to avoid talking about her previous pieces and, yes, she confessed to growing tired of certain labels, the eternal referencing of the Movida to explain her practice. Suddenly the conversation flowed in other directions, related to our current times and how they’ve led to new discoveries in relation to materials, missing nature and the earth, and drawing, textures, and pleasure. We talked as if we knew each other somehow, and for the photos we were joined by Bárbara’s daughter, fashion designer María Rosenfeldt. The talk left the impression of a bond that will surely continue to grow; her voice was beautifully kind, and I hope you will also become a friend of sorts to Ouka Leele after reading this conversation.

close

close