How did the shop start? When you took it over, was it already selling clothes?

I was really forced to get the shop. This German guy from Morocco showed me the place at night, locked me inside, gave me enough to smoke, and kept pushing and pushing me to buy the place. In the end he came down so much with his price that I thought, ‘Well, OK, next week I can sell it again. I can always sell it for more’.

That’s why I say it’s not a dream I had: ‘I’ll go to Ibiza and open a boutique’. What the hell did I have to do with clothes? I was an architect.

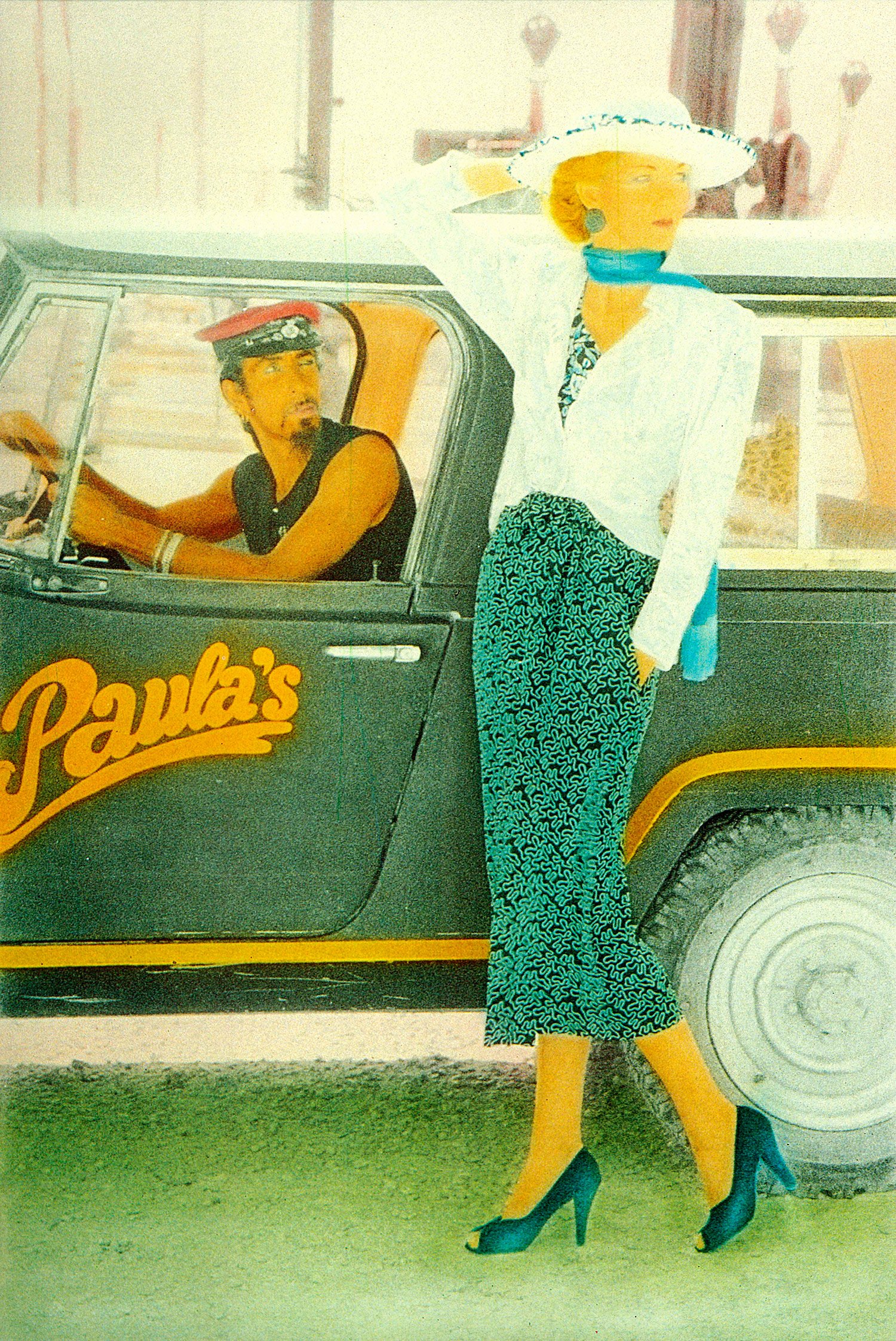

I left the shop without touching it. And when I went back a month later I found a note from a German lady who had bought a blouse there and wanted to order more pieces. She described its design and this blouse was hanging there. So I found a shop selling curtain material. And then, in a notebook, I found the name of the seamstress, Antonia, but no address—and that was the beginning of a new adventure. I had to drive over the whole island looking for her. I went to each and every farmhouse and I got to go inside all the houses and see how people were living. It was just incredible.

And finally I met my Antonia. She made me the blouses and I sent the package away, and the lady sent me the money. ‘Well’, I thought, ‘Perhaps she can make some more blouses or some more dresses’. That’s how it started.

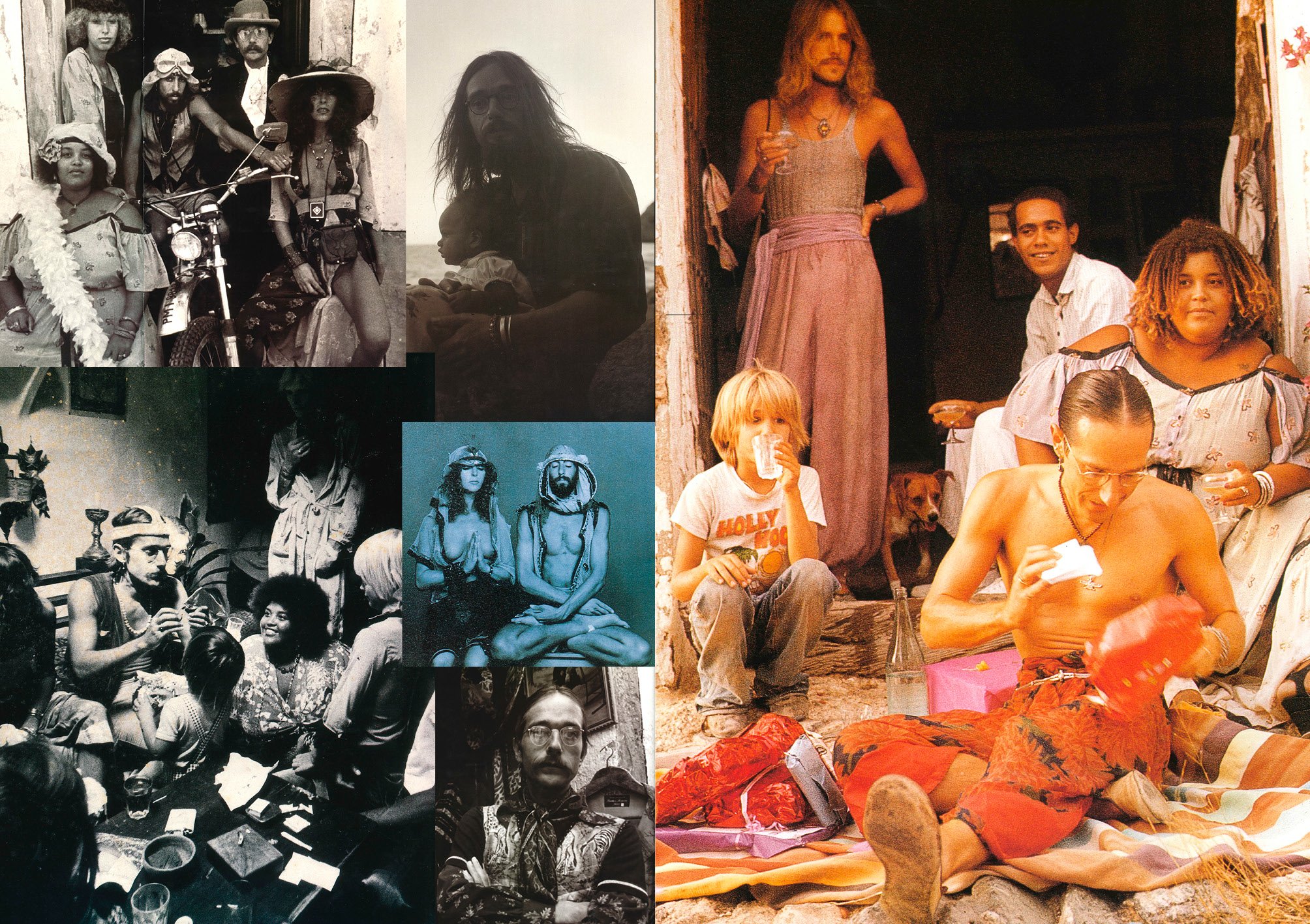

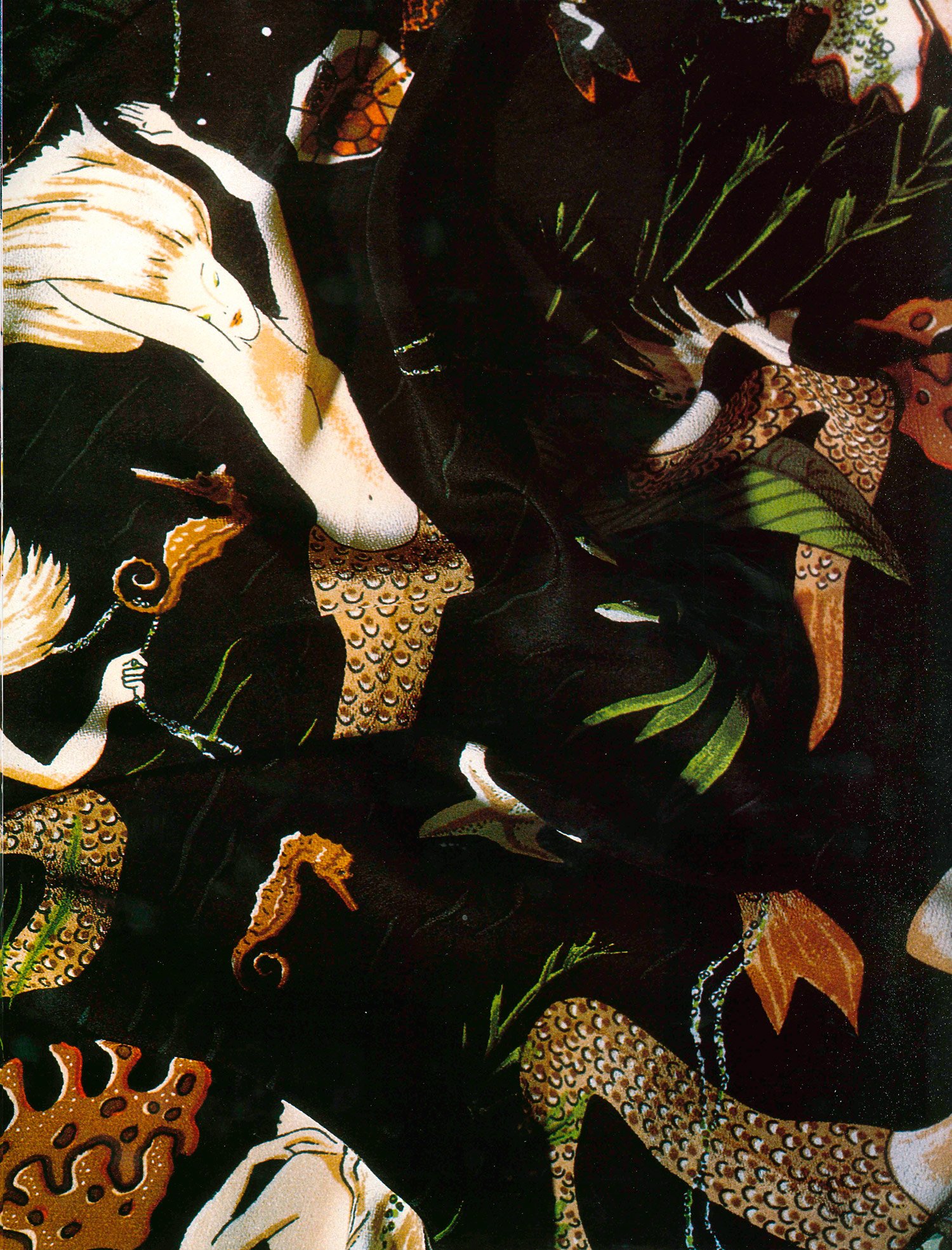

Then one of my hippie friends said she knew about patterns and sewing and I brought her to the seamstress. But when she started to speak to Antonia they were not able to communicate and the conversation became so complicated that I decided to leave the professional out of the story. So I said, ‘Well, listen, Antonia, you still have the pattern for a dress, let’s try to do something with it’. And I bought the fabric. But Antonia was in her own world. The result was an accident. The fabric was used from the wrong side and the dress was longer in the back and shorter in the front.

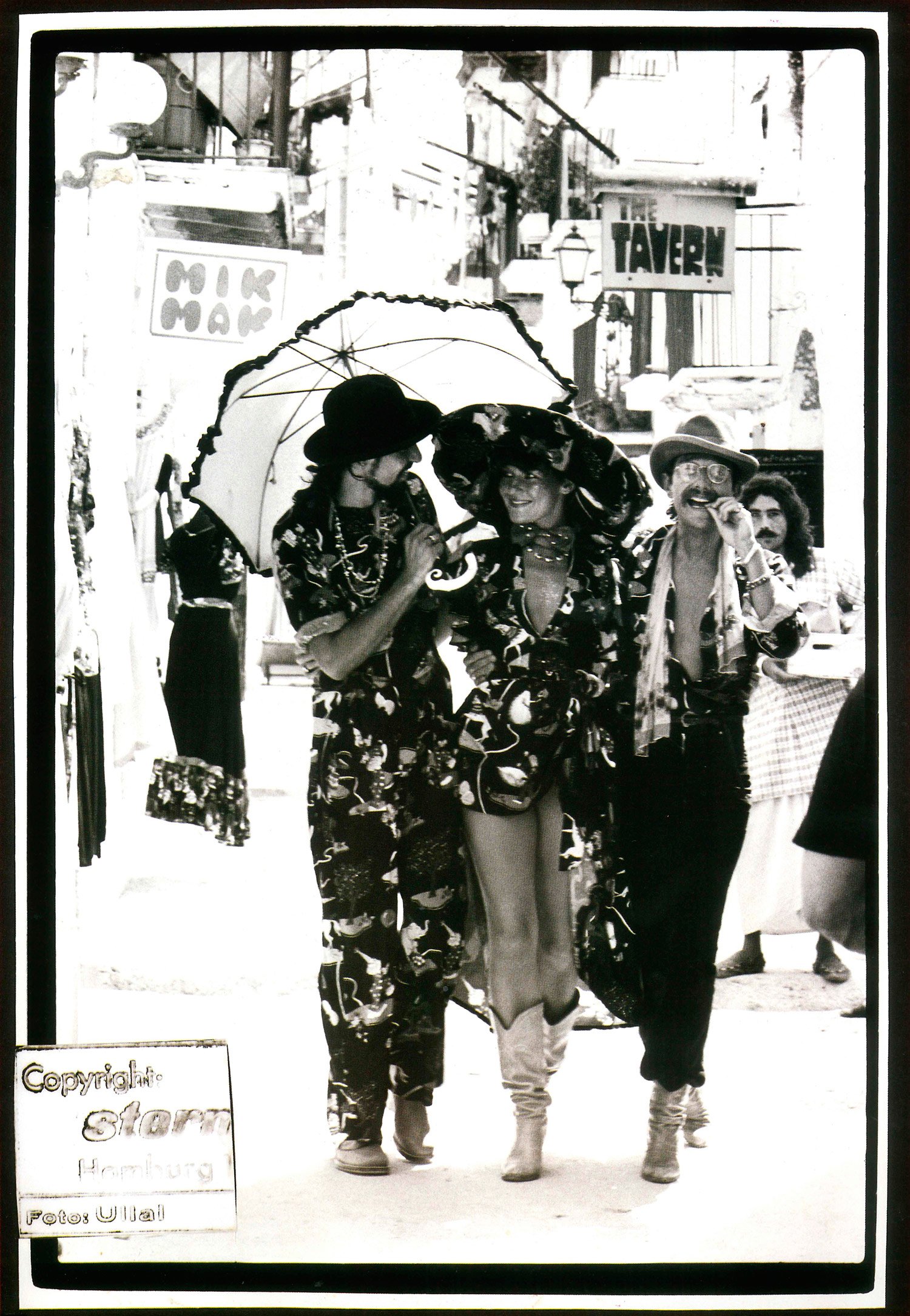

But struggling as I was, I said, ‘Well, that’s OK’. I put it in the shop and I was more than surprised that it sold right away. People thought it was beautiful, and so I continued. Then I met Stuart, who was sitting in the street in the old town, selling herbs.

Herbs to eat or herbs to—

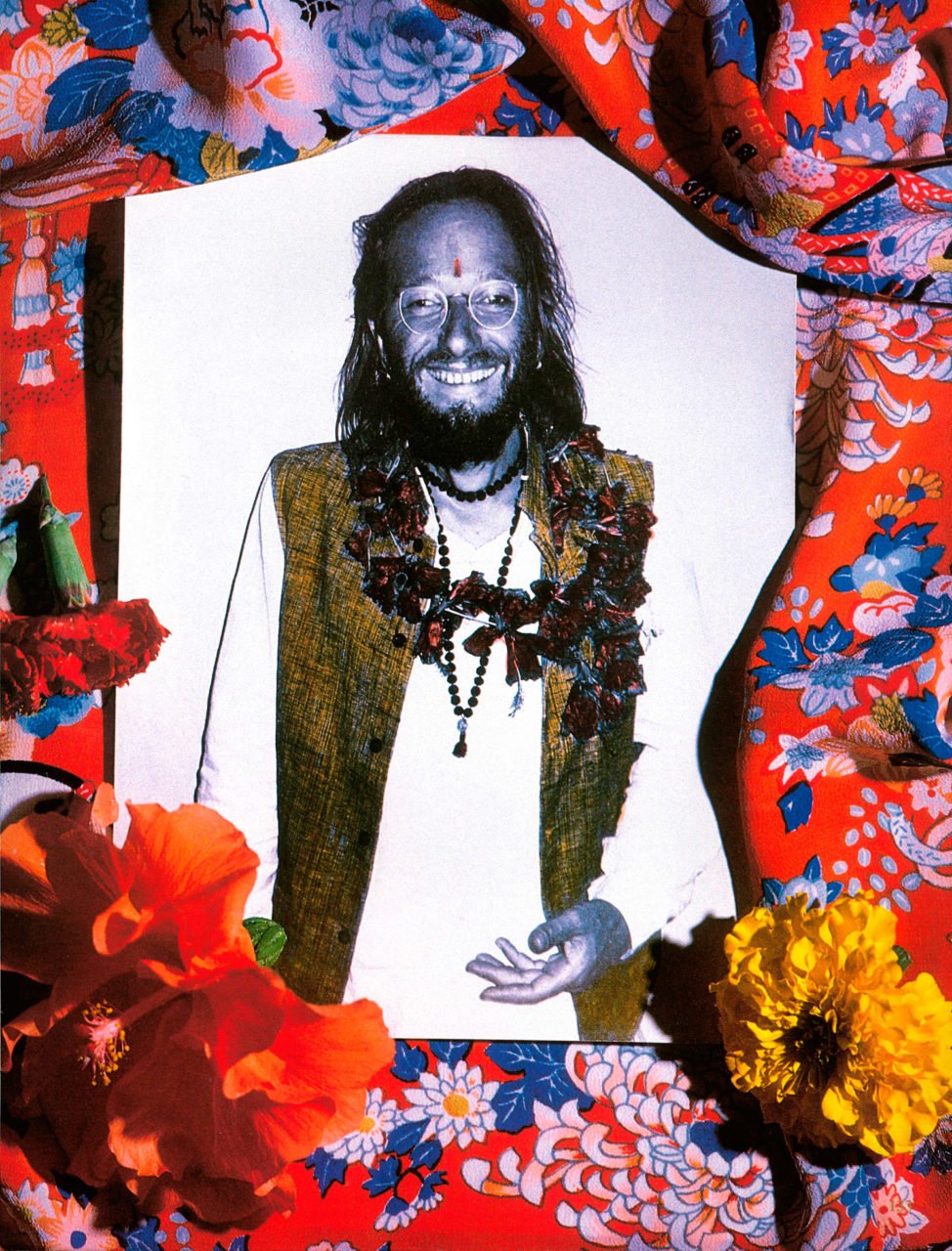

No, no, to eat. Imagine this 23-year-old American boy coming here to San Juan like me, and wondering how to make some money to live. He would go to the woods to pick herbs, like rosemary, thyme, sage, then collected old papers that were thrown out from the tobacco shop, ripped them into small square sheets, got some coloured pencils, and drew pictures of herbs on them. He added some written explanations, like ‘rosemary for remembrance’ or ‘thyme for breathing’, folded them into little packages, filled them with the herbs, and wrapped some cord around them that he’d found in the street. He put everything in a jute bag, hitchhiked 24km to Ibiza, spread out his bag in the street, decorated the herb packages on the bag, and sold them to tourists for 25 pesetas each. I was impressed—a business with zero investment. I thought he was a genius businessman.

Streetwise, for sure. But what did you need him for?

When the shop started to pick up I realised I needed someone to help. I had my two- and three-year-old children in San Juan. I would give them enough food in the evenings, put them to bed, leave the door open, and go into Ibiza. Nowadays, the police would come and take the children.

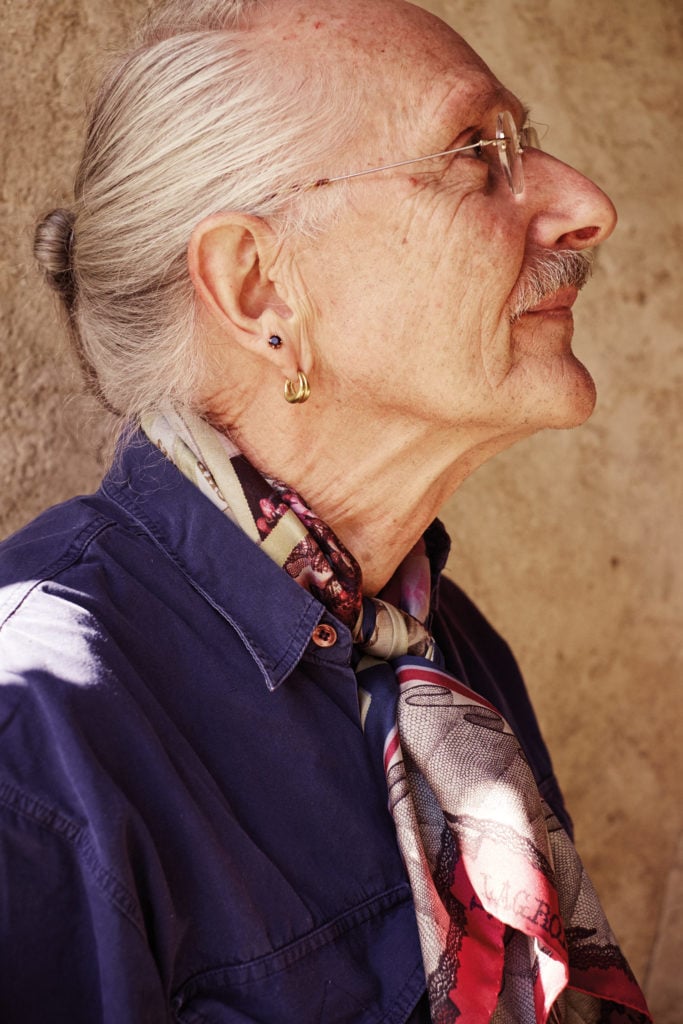

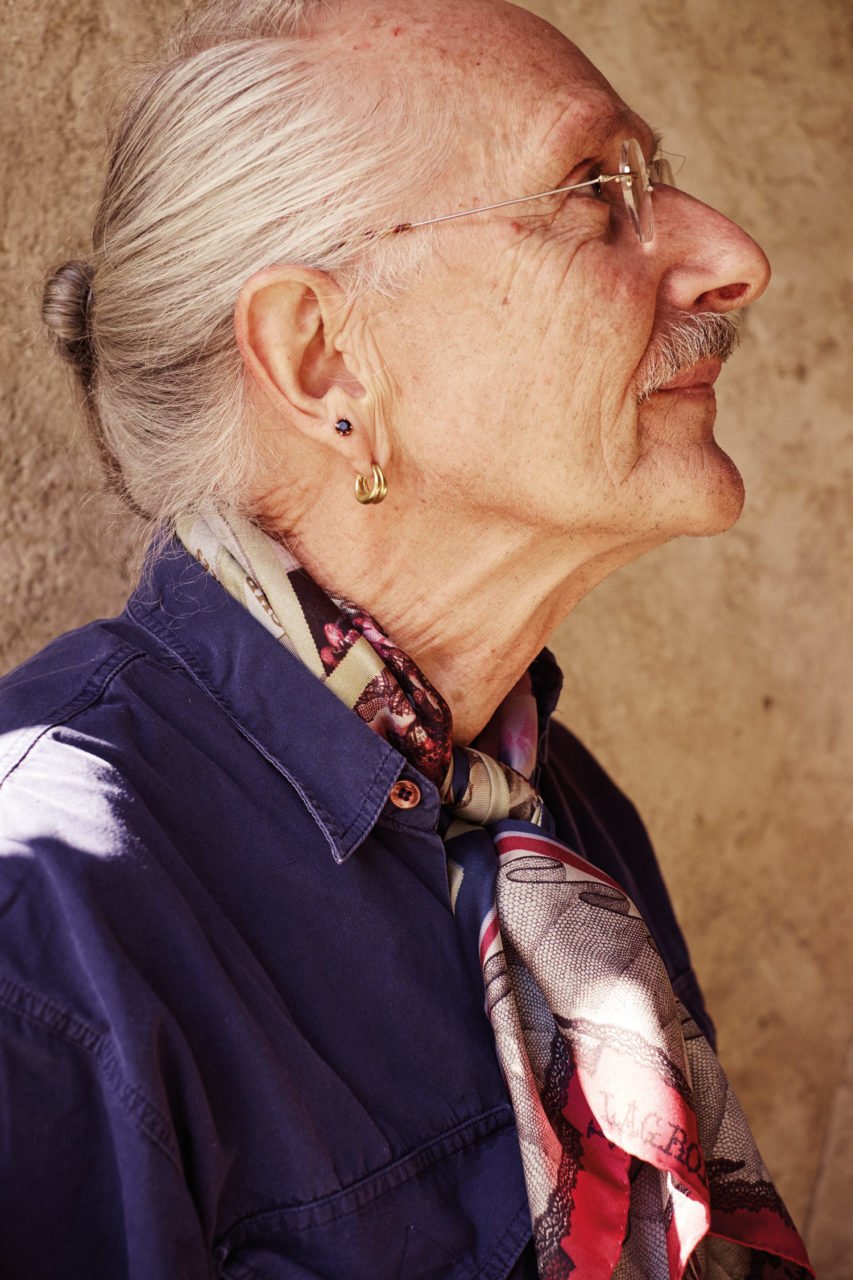

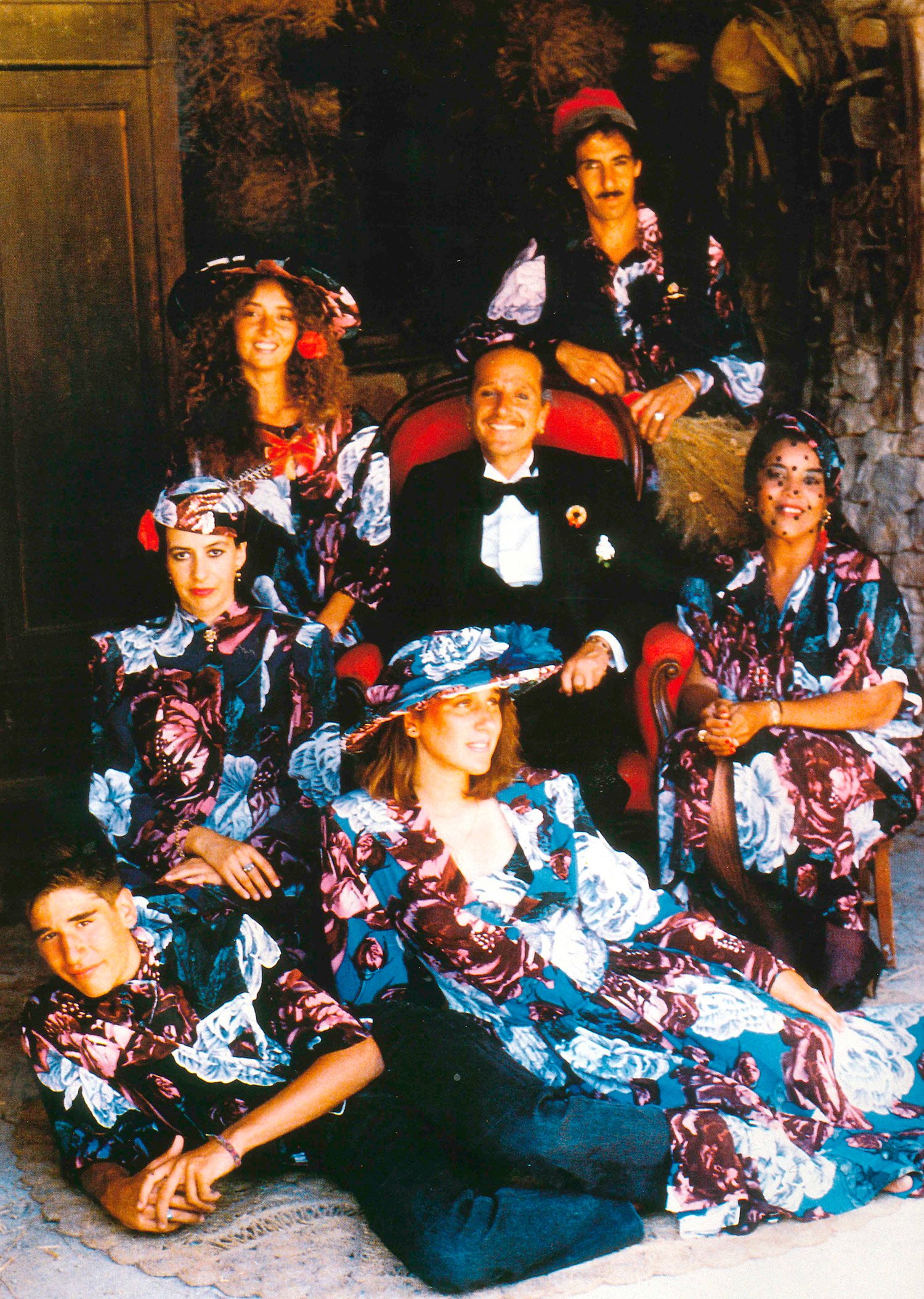

Stuart was willing to help; he was a good, selfless worker, very creative, and he had an incredible sense for beauty and art. He turned out to be really the guy. I mean, we are still working together today, and he is incredible.

Did you have the feeling you were doing fashion, or didn’t you think about it?

Well, I don’t know. I never wanted to do fashion like what I saw in the fashion magazines.

What was your aim when doing the clothes?

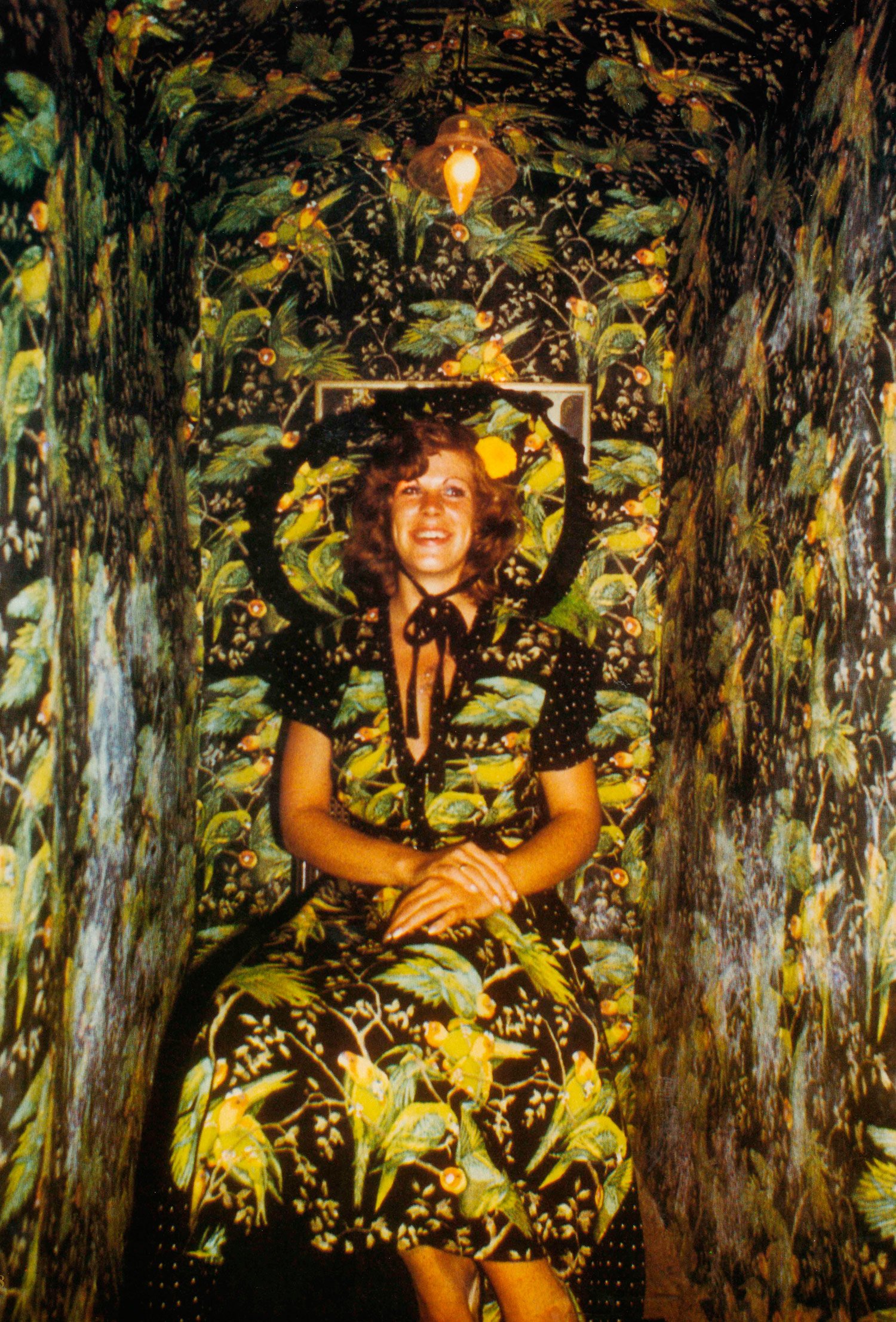

It was just about discovering my own creativity—what I was feeling, what I was seeing in nature—and transforming all my experiences into what I was doing; in this case, designing clothes.

close

close