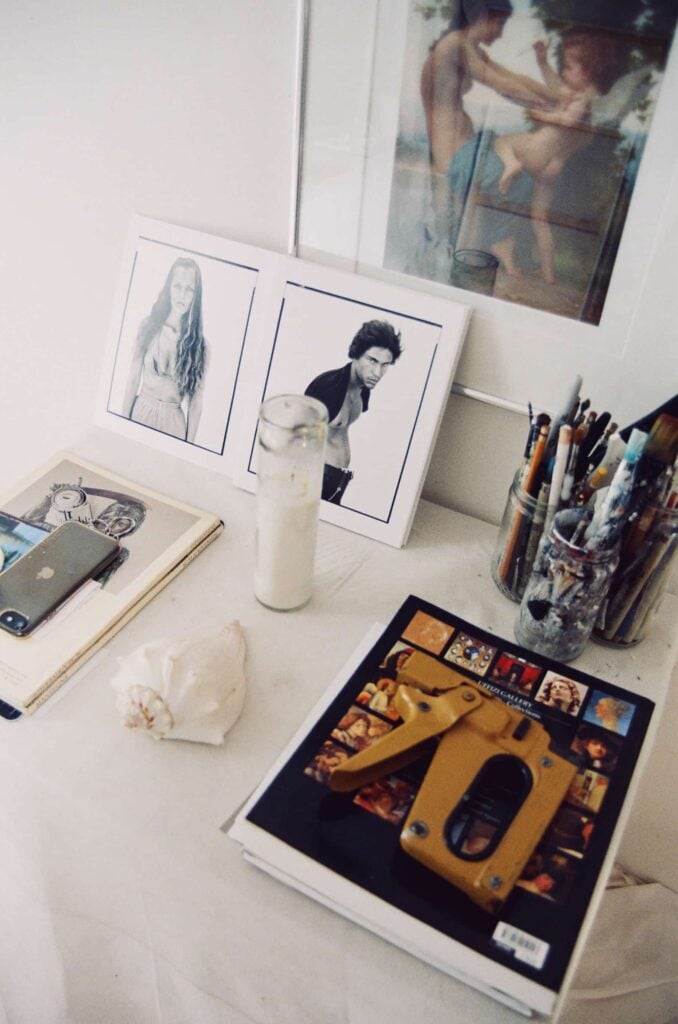

New York City: It’s a steamy, white-hot afternoon at August’s end. The sun is a bubbling lava pool; beneath it, Brooklyn is drenched. The artist Andrea Smith greets me at the entrance of her Clinton Hill apartment building, one foot hovering in mid-air. Wearing a black, bias-cut slip dress and gold chain with spiral pendant (a totem inherited from her Greek Orthodox grandmother, who wore it beside her crucifix), Smith is the most glamorous person I’ve seen on crutches in recent memory. We walk-hop into the cool of her studio, a small, sunlit alcove attached to her living room, as she explains that the injury was the result of a comedy of errors. It involved a fall from a kiss, crushing her lower limb. There are now eight metal pins in her leg.

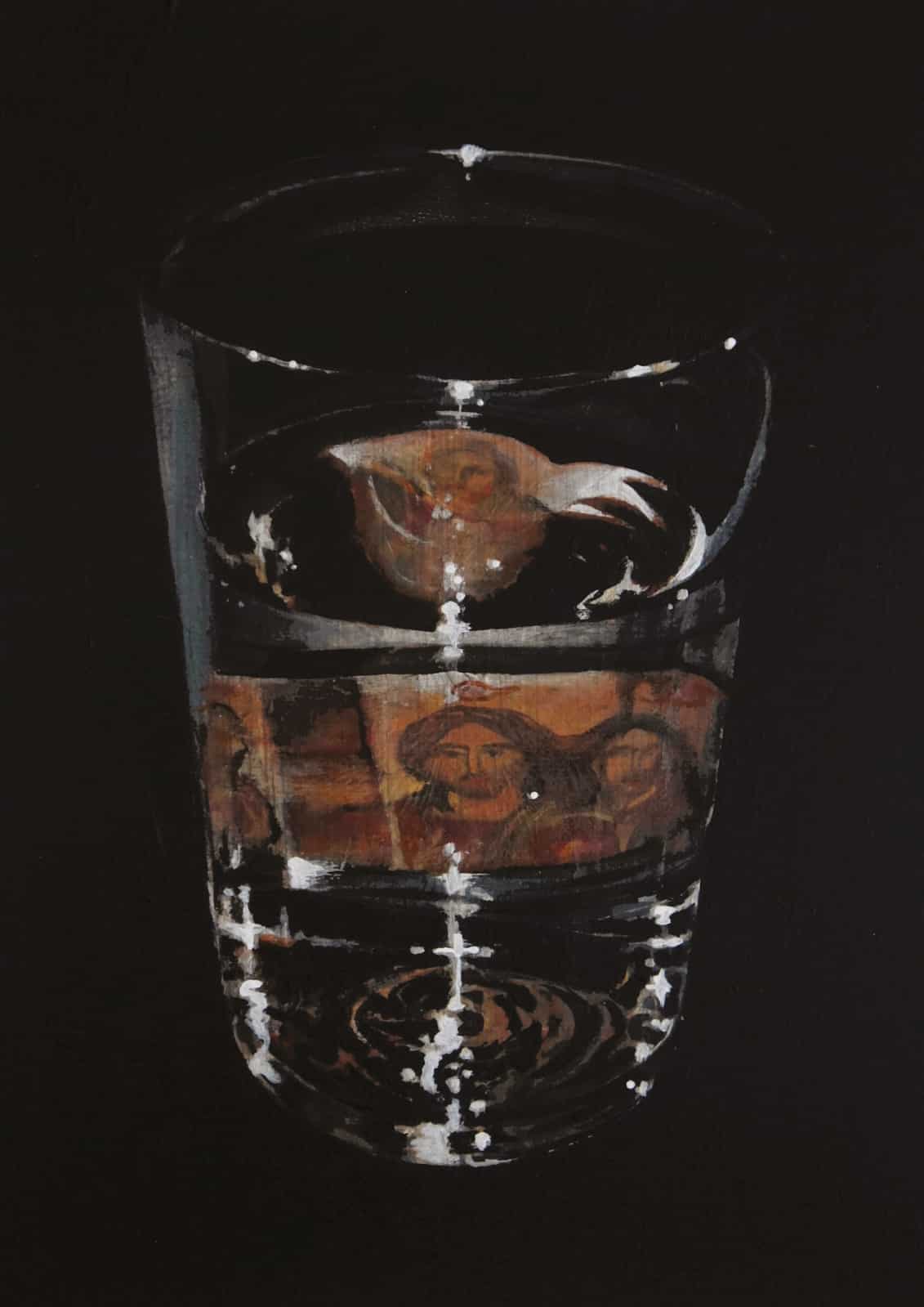

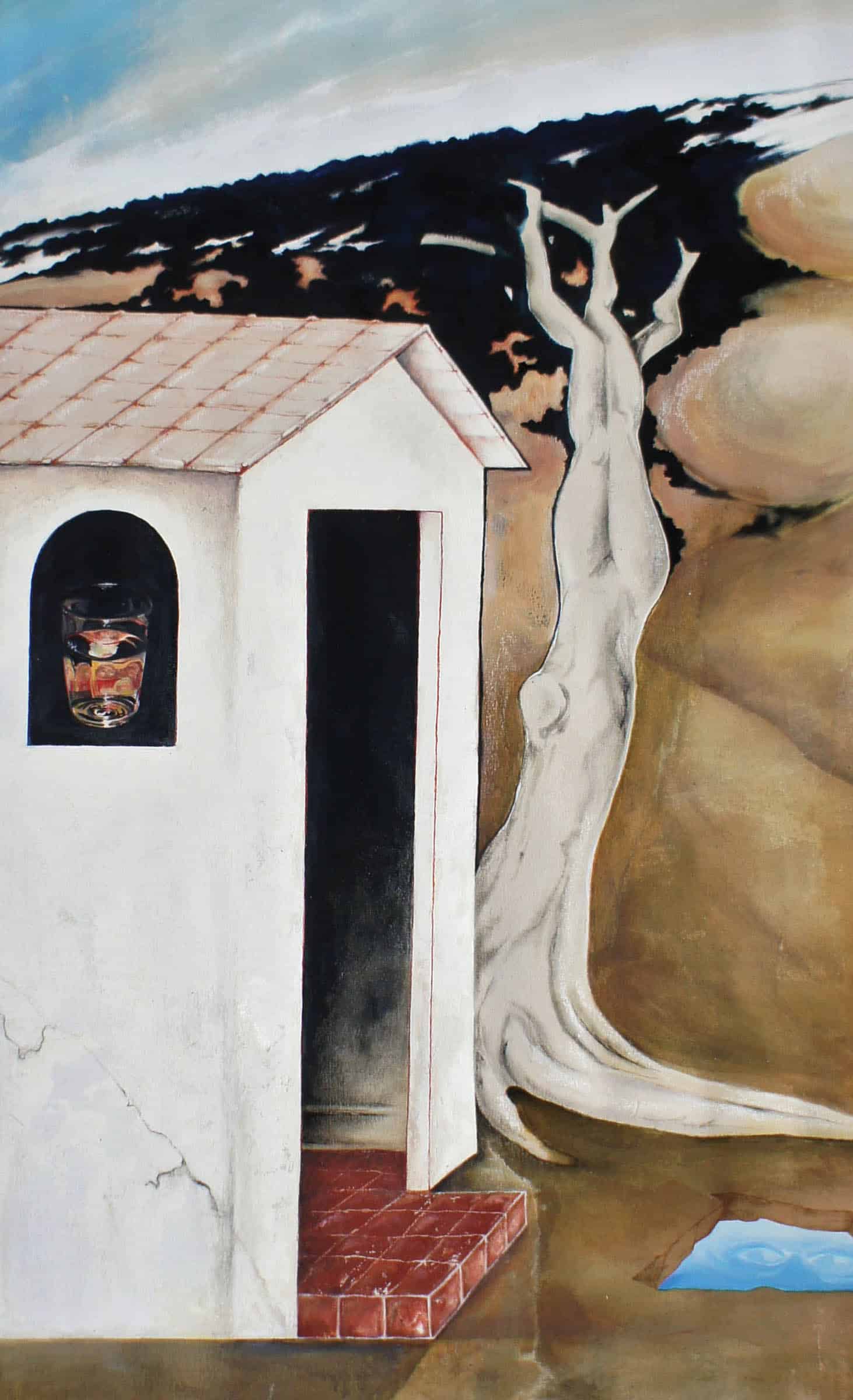

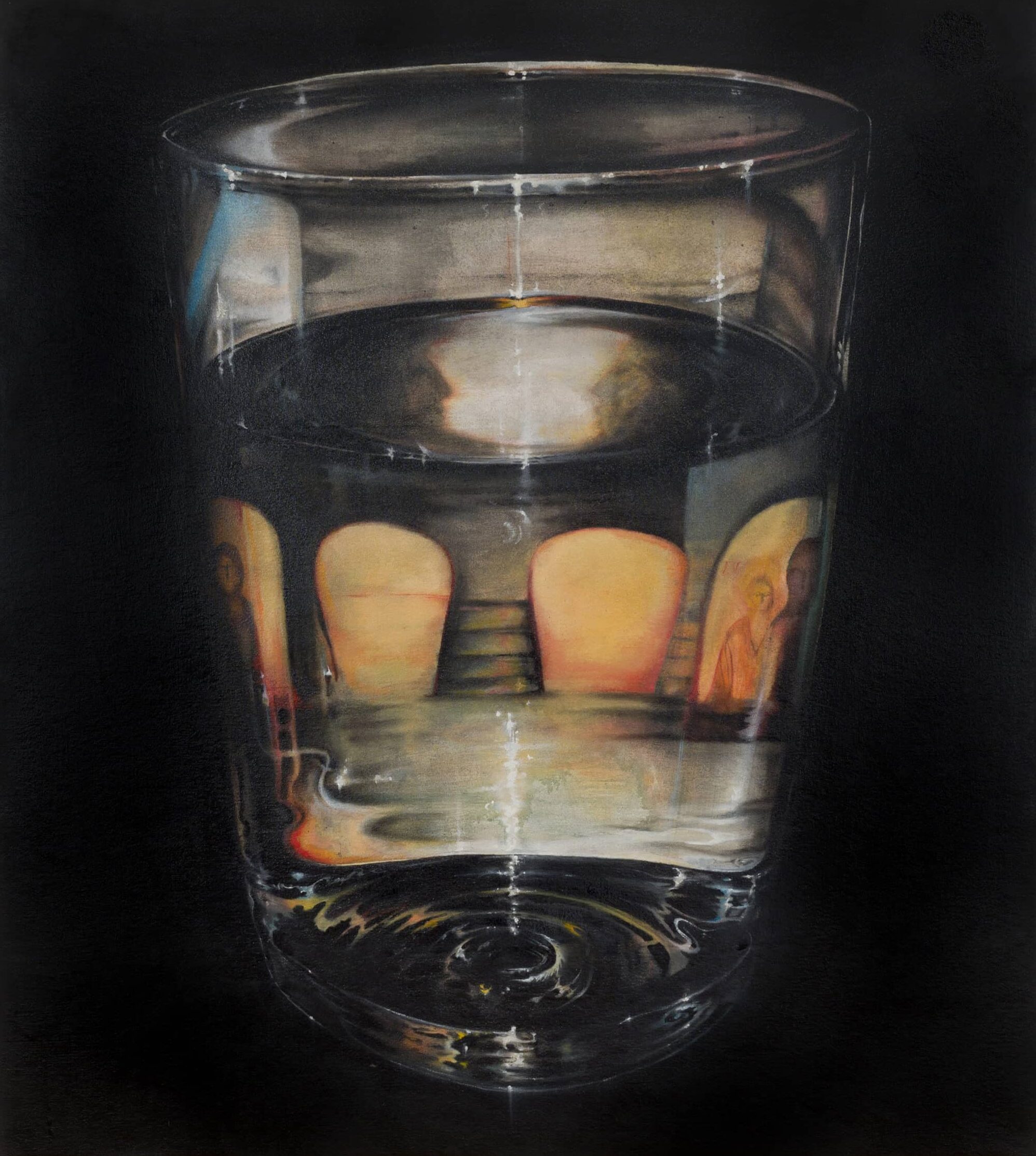

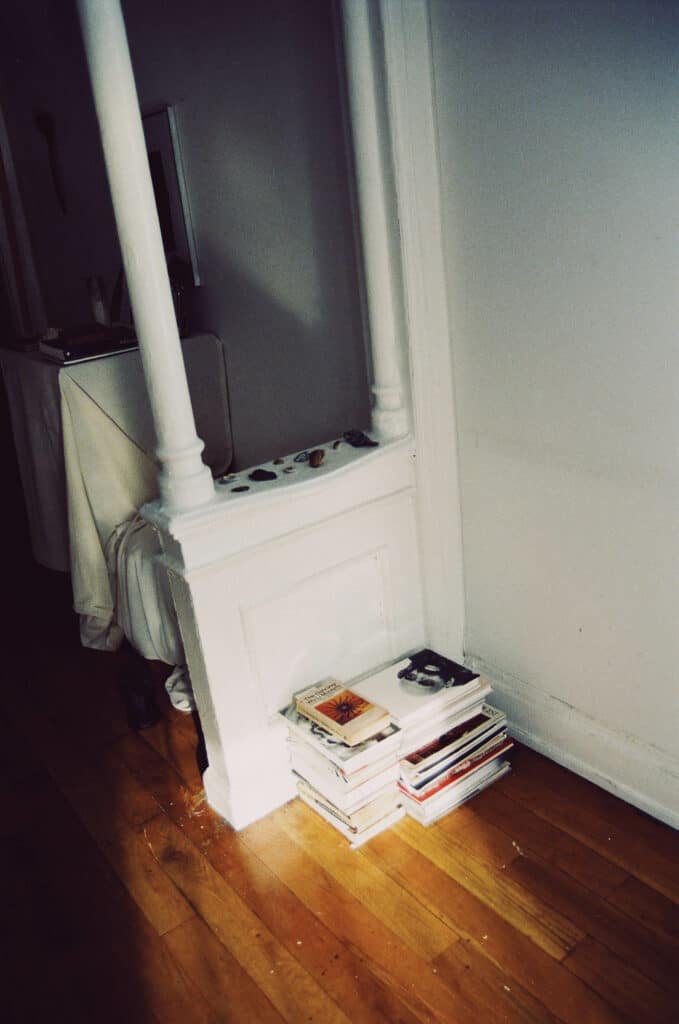

To attack the sprawling canvas she’s midway through when we meet—a mythic, quasi-religious scene which employs an entire wall of her studio—Smith scuffles across it on one foot. ‘I’m like a flamingo these days’. Luckily, she’s had plenty of practice shrinking her physical world—isolated in long stints over the last few years, like the rest of us, and, strangely enough, via painting, where she often prescribes herself limitations or repeats specific motifs, like flowers, seashells, spirals, and disembodied, Magritte-like eyes. Case in point: the stack of small boards propped against her studio wall, each featuring a single glass receptacle against a jet-black backdrop and rendered in oils. There are water glasses, wine glasses, goblets, jars, and vases, all replicated with the quiet zeal of a Renaissance apprentice and using pigment she has ground and mixed. (She sometimes adds natural materials to her varnishes, like lavender.)

Smith’s practice is entrenched in painting, but extends to photography, painted clothing, print design, and creative direction for projects like her limited-run newsprint, The A.M.S Sun. Our conversation kept returning to her latest paintings, which unfold like fables populated with her enduring fascinations: the female body; creation narratives; temptation and virtuosity; the Greek Orthodox church; seeing and imagining; the sublime mundane; symbols of life and its circularity; and the intricate, generational threads that connect us to one another and to the earth. Partially indebted to ‘30s Surrealists, Smith increasingly echoes their compositional lyricism and their appeals to a collective subconscious—even as her images derive from waking memories. After our conversation, I began re-reading the few existing English fragments from Surrealist-adjacent writer Joë Bousquet: pictorial, desirous phrases that seemed to rhyme with her work and hint, too, at something eternal, like ‘a body made of wind and sunlight’.

close

close