Originally published in Apartamento magazine issue #35. Lina Soualem is a director and actress born in Paris. She has directed two feature-length documentaries, Leur Algérie (2020) and Bye Bye Tibériade (2023), the latter of which was chosen to represent Palestine at the 2024 Oscars and was nominated in the Best Documentary category at the 2025 Césars.

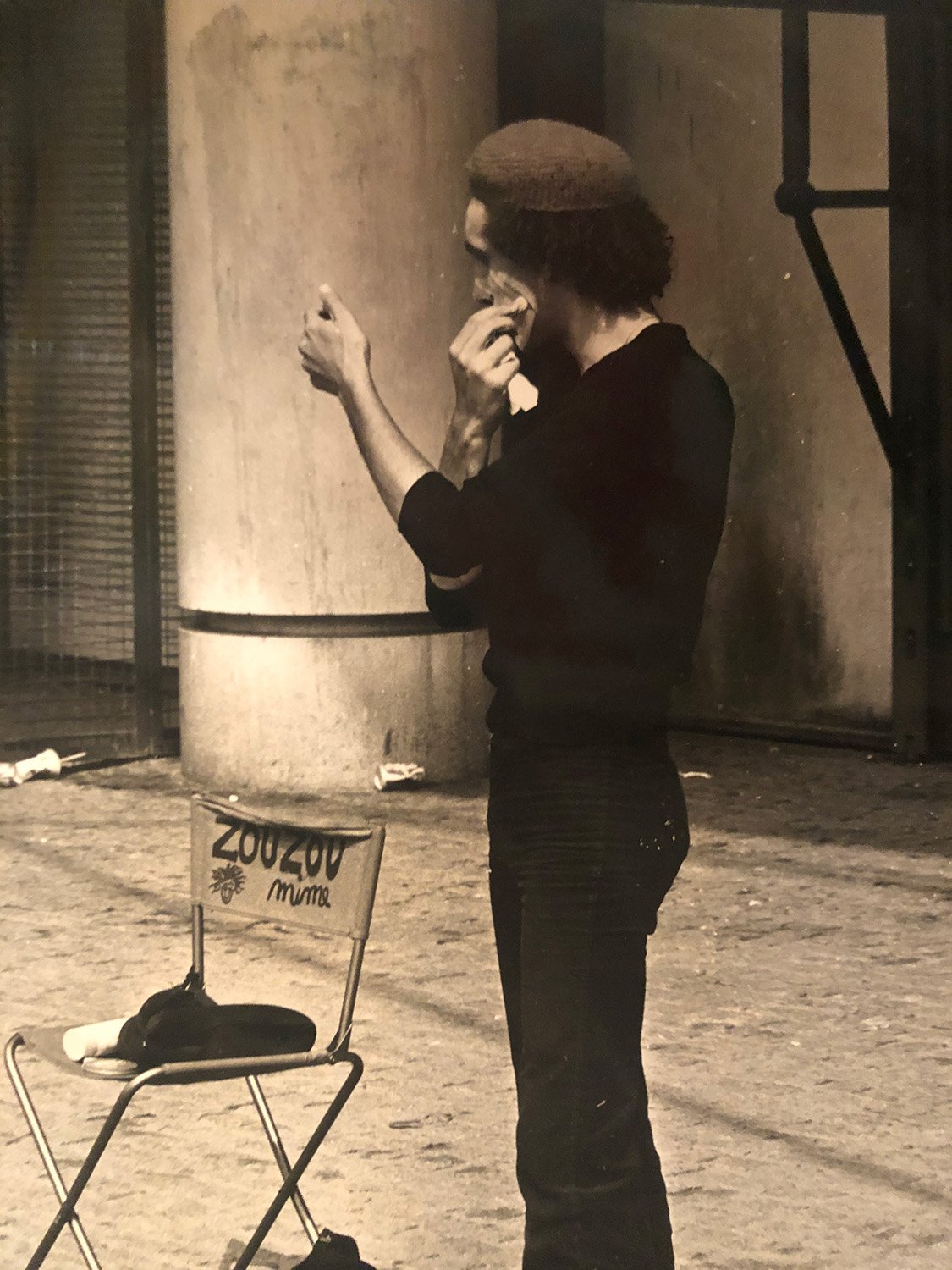

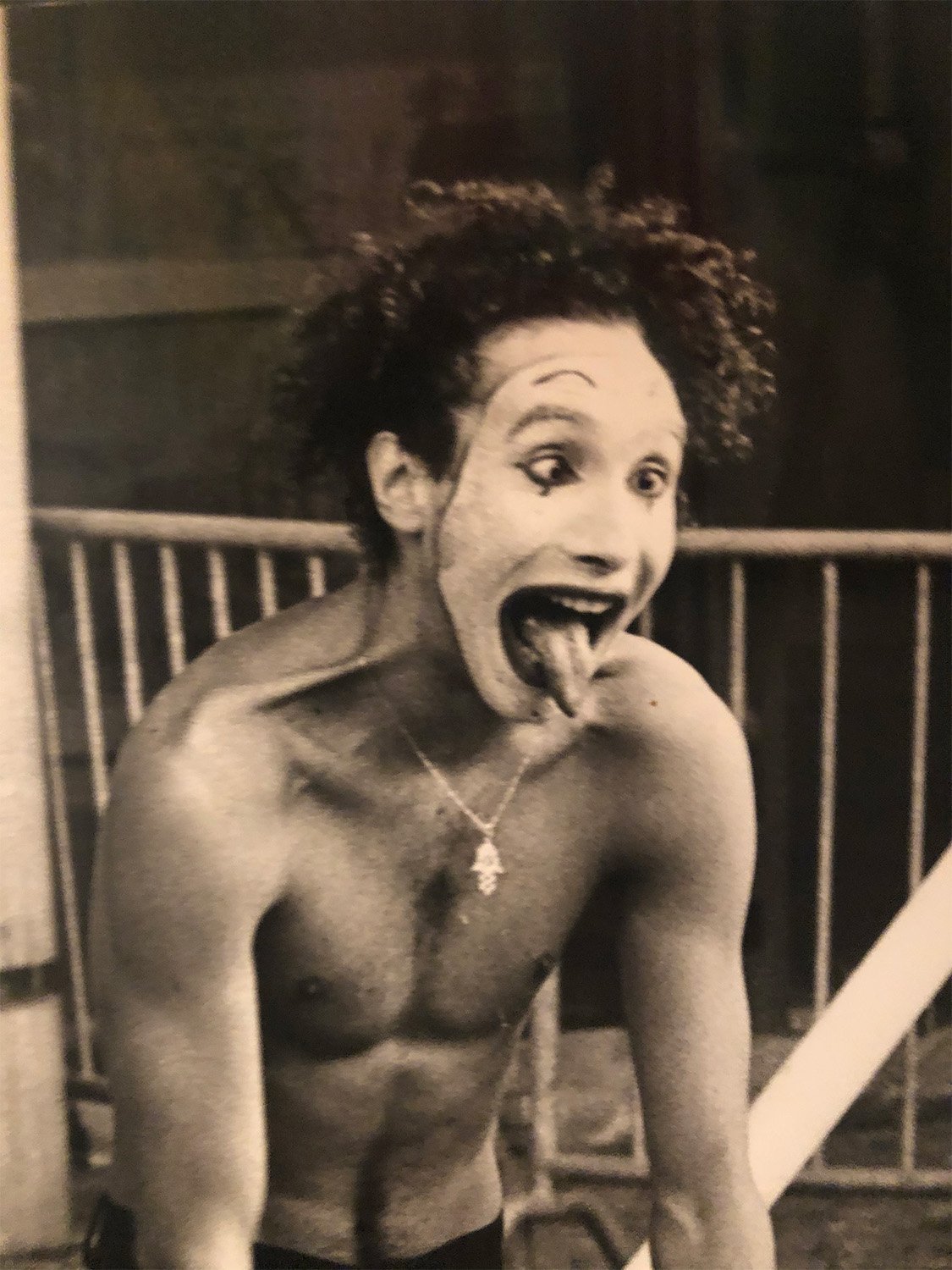

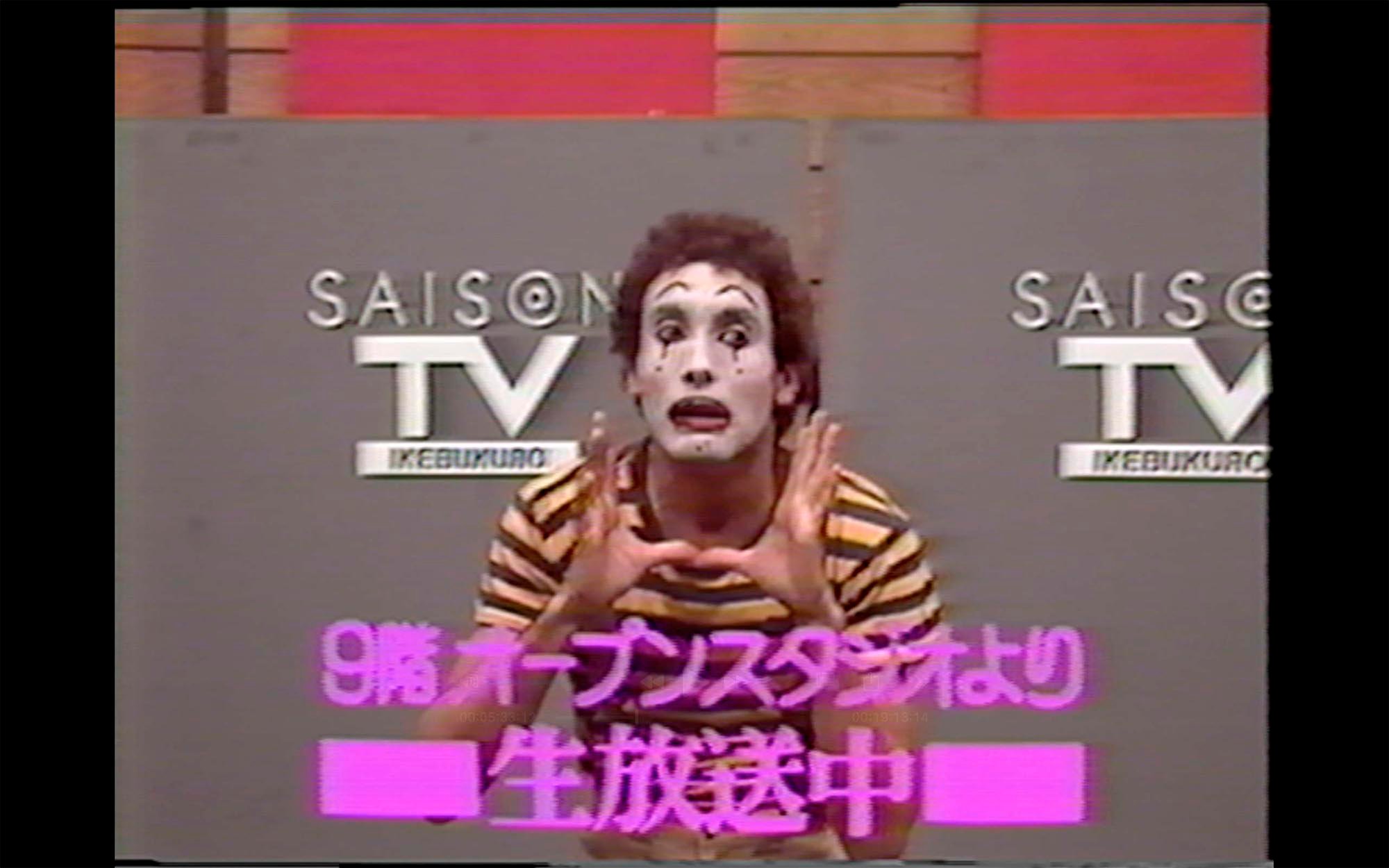

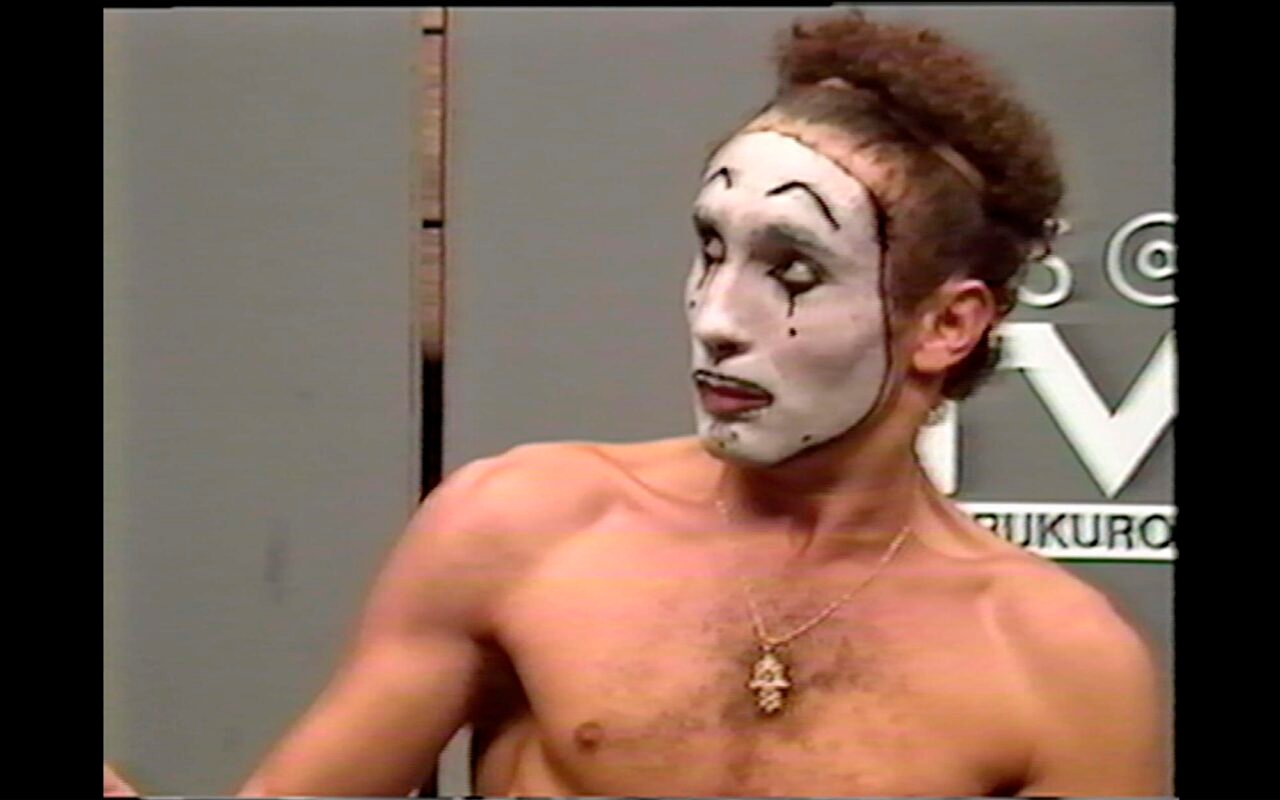

Zinedine, my father, became a street mime at the age of 18. His artist name was the Mime Zouzou.

‘I only wore dungarees and striped sweaters at that time’, he once told me. Other than that, the only memory he shared with me was travelling from France to Peru for three months to do street mime. How did he end up there? Apparently, he’d met a Peruvian mime in France who convinced him to go to Peru with him. At the time, my father travelled with his Algerian passport, and the Peruvian officials didn’t know what Algeria was, so they held him for hours. At some point, they took out a map of the USA and asked him: ‘¿Dónde está Argelia?’ (‘Where is Algeria?’), thinking it was a state they had never heard of. I picture a young 18-year-old Algerian mime, taking a plane for the first time, crossing the Atlantic for the first time, sitting in an immigration office in Lima’s airport in Peru, facing a map of the USA, a country he’d never visited, holding his Algerian passport, not speaking a word of Spanish, being asked repeatedly:

‘¿ARGELIA? ¿¿DÓNDE?? ¿¿¿DÓNDE???’

Zinedine’s parents, Aïcha and Mabrouk, immigrated from Algeria to France in the early ‘50s, not by choice, but to work as cheap labour in French factories. My grandfather worked in a knife factory for decades: ‘I worked undeclared—we did prisoners’ work’. He remembers his French colleagues telling him: ‘We brought you here to help out—not to earn more than us’.

My grandparents came as colonised subjects of France, stripped of their Algerian identity and deprived of their rights. The French colonised Algeria starting in 1830, and they considered it to be a department of France, under colonial rule. They considered it theirs.

Zinedine was born in France in 1957. In this context, he was born as a colonised subject of the French colonial empire. Five years later, in the summer of 1962, the Algerians finally gained their independence from France following 132 years of colonisation and eight years of a brutal war. A war that killed many members of my family.

At age five, Zinedine stopped being a colonised subject and gained his Algerian citizenship. A citizenship that was obtained by force, after a hard struggle for liberation.

As a child, he thought (he hoped!) they could go back home, but they never did.

close

close