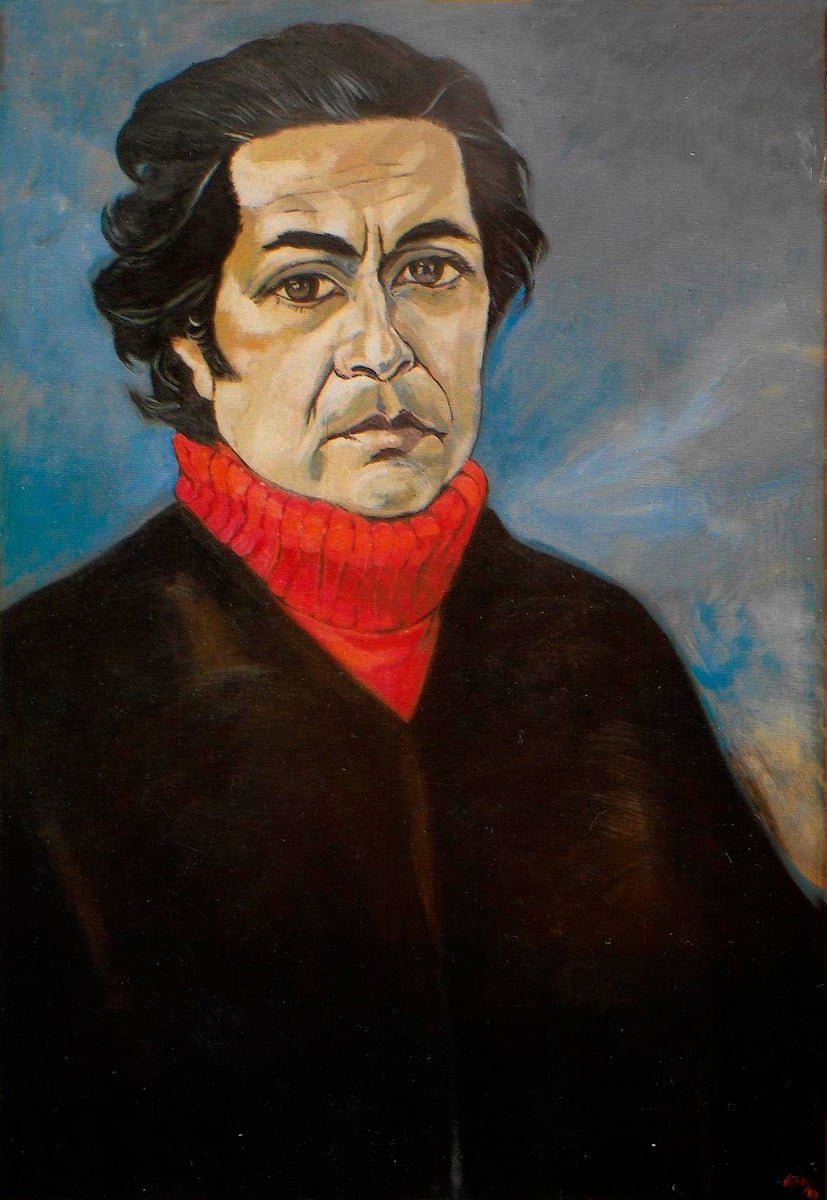

Set atop a hill in what used to be the northern outskirts of Quito, Ecuador, a haven of devotional Spanish colonial art, indigenous Andean treasures, and bullfighting instruments and paraphernalia greets me. Overlooking the Pichincha volcano, the casa-museo of octogenarian artist Oswaldo Viteri is home to a jaw-dropping collection from all periods of Ecuadorian art, as well as pieces from other countries and his own paintings, drawings, and sculptural work. The house was built by Viteri himself, a trained architect, in the early ‘70s. The polished clay tiled floors and wood-beamed ceilings recall early vernacular constructions. Viteri, at the age of 88, still reads and works every day in his house, among the white-washed brick walls and the contrasting dark red curtains falling heavily onto the wooden floors, reminiscent of a bullfighter’s cape.

My father was an architect. But if you’d have asked him what he would’ve liked to have been instead, he would have said torero. Viteri would agree, had circumstances not favoured his true passion for art. I’ve often witnessed how bullfighting lures the minds of art and architecture enthusiasts—a fellow college classmate of mine dropped out to become a matador—however, the art of bullfighting is only one of Viteri’s passions.

Viteri grew up in the early ‘30s in the small Andean town of Ambato. He recalls spending time on his grandmother’s farm, discovering the countryside, the ancient traditions of caring for land and crops, while also happily roaming with the children of the farmers. He also attended corridas at the Plaza La Macarena from a very young age and was always intrigued by his grandfather Julio’s passion for cockfighting. His training as an architect gave him expertise as a draftsman, while his upbringing provided empathy towards cultural identity. Since very early on, Viteri’s practice has been informed by an interest in anthropology, folklore, and genealogy. I spoke with Viteri’s daughter Ileana—an architect, professor, and former gallerist—about growing up in Viteri’s extraordinary world.

close

close