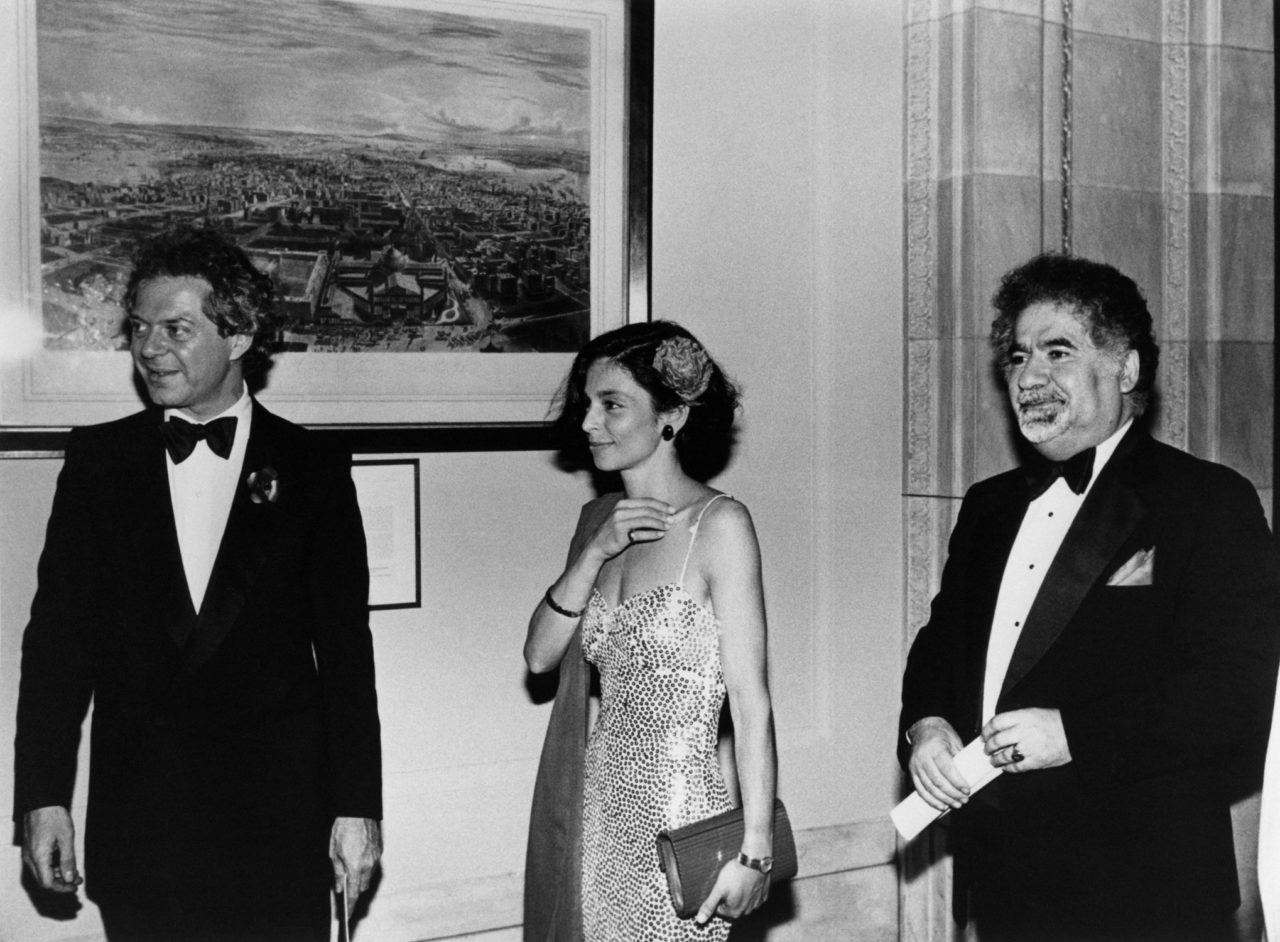

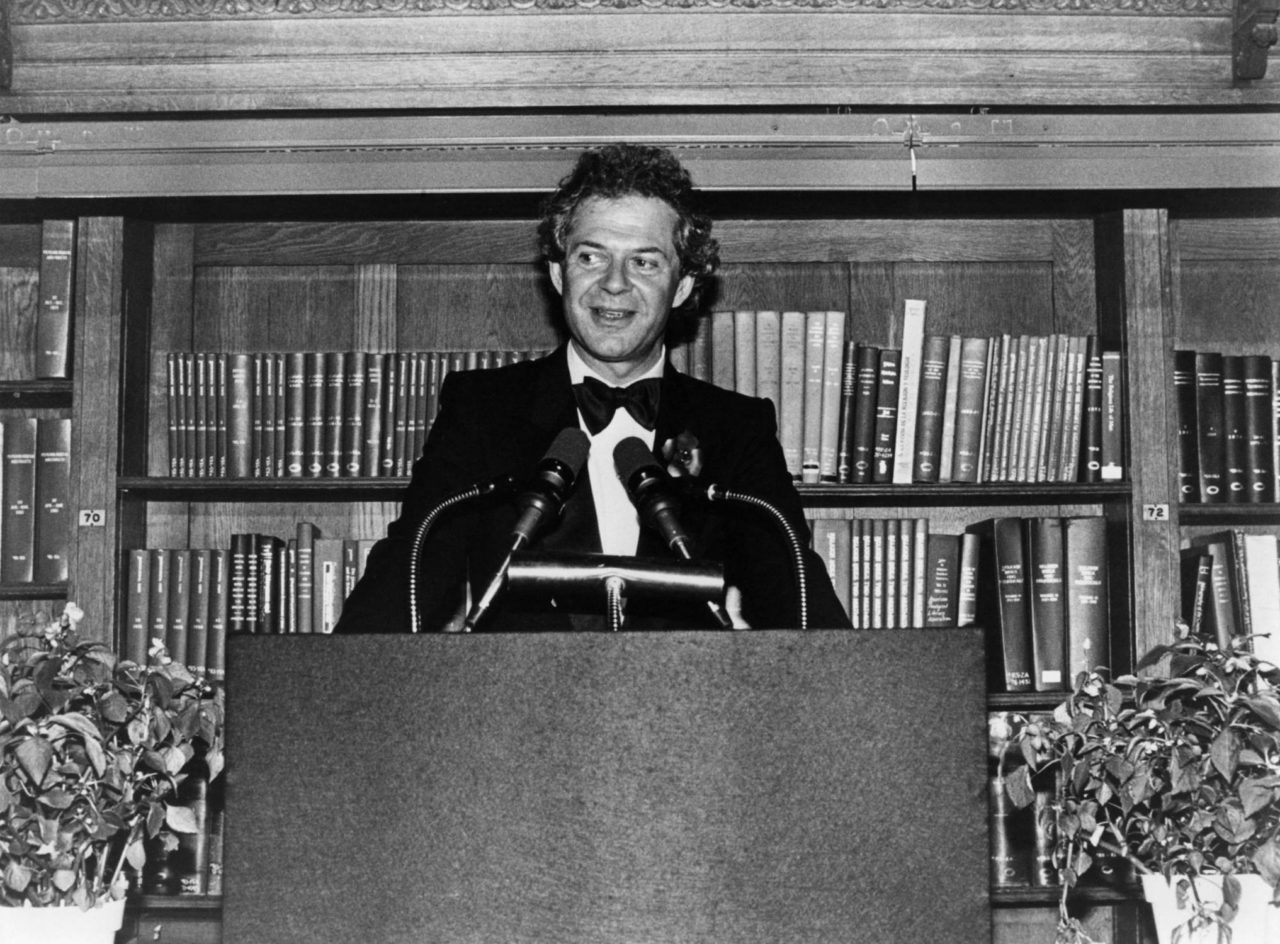

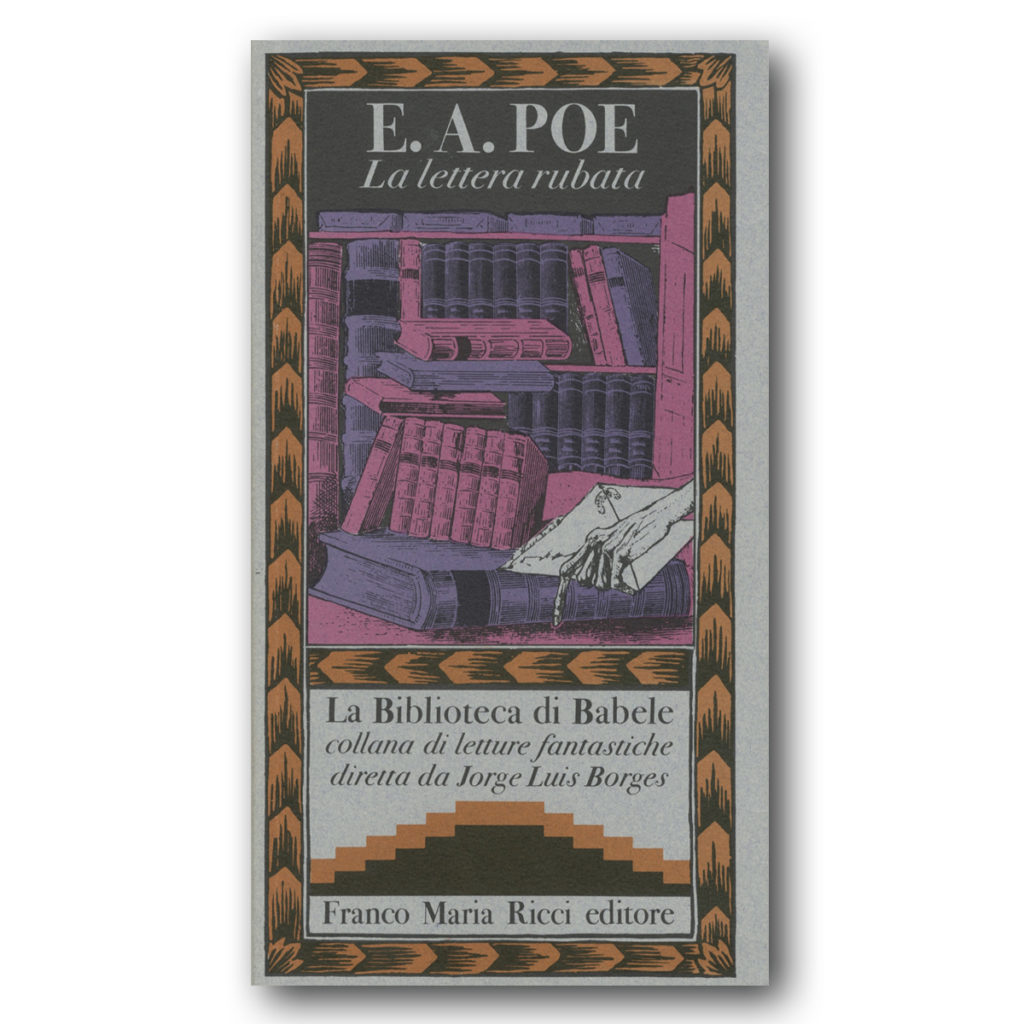

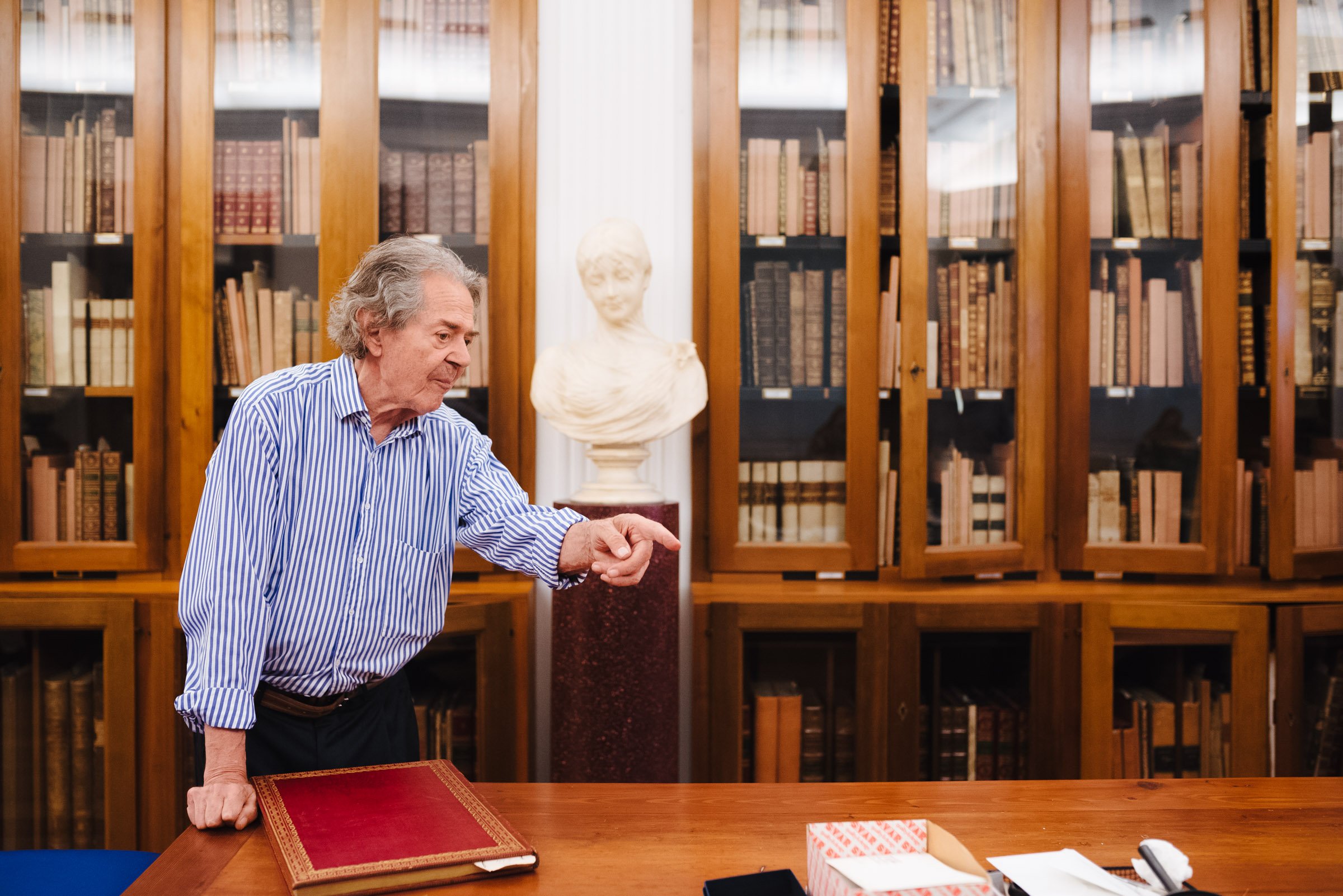

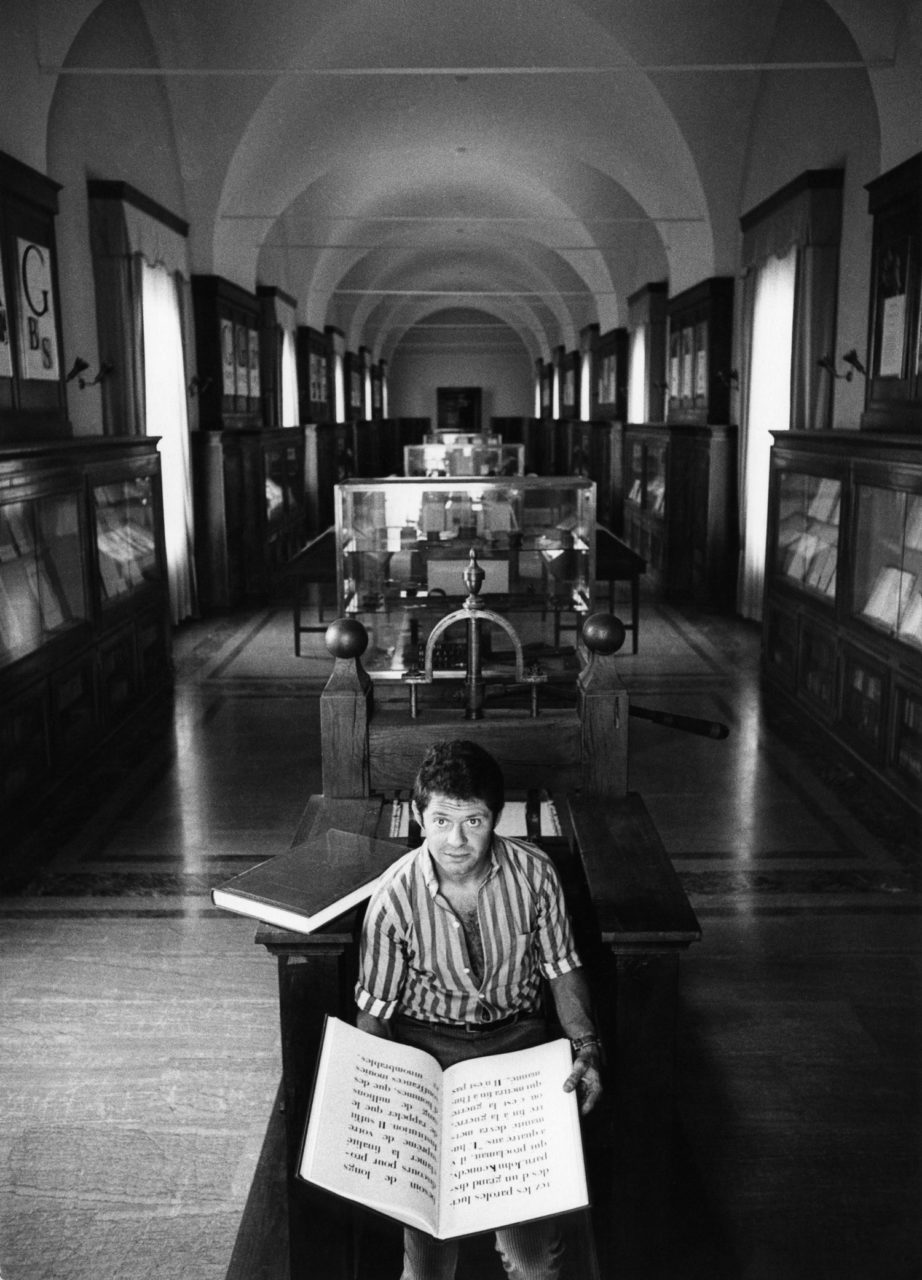

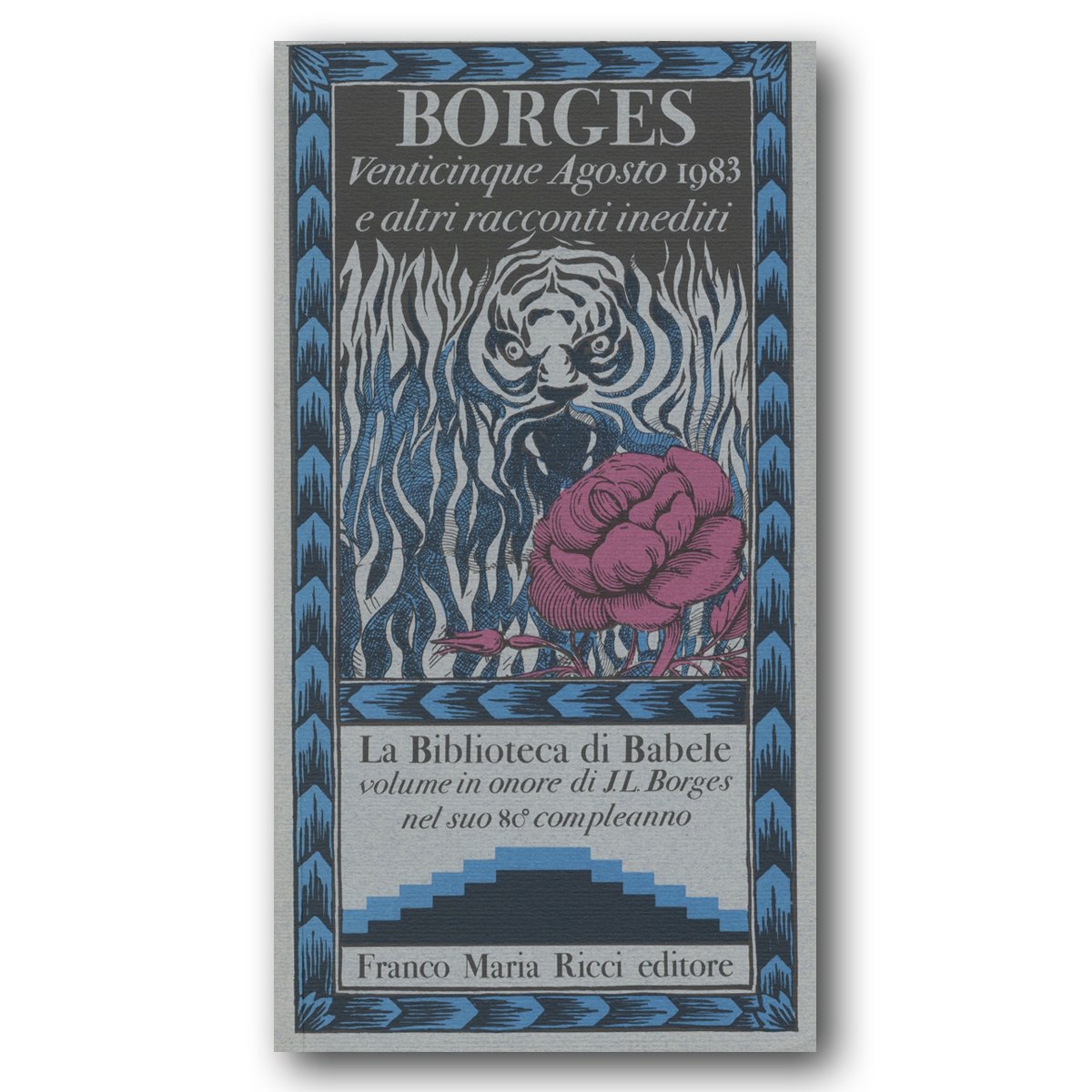

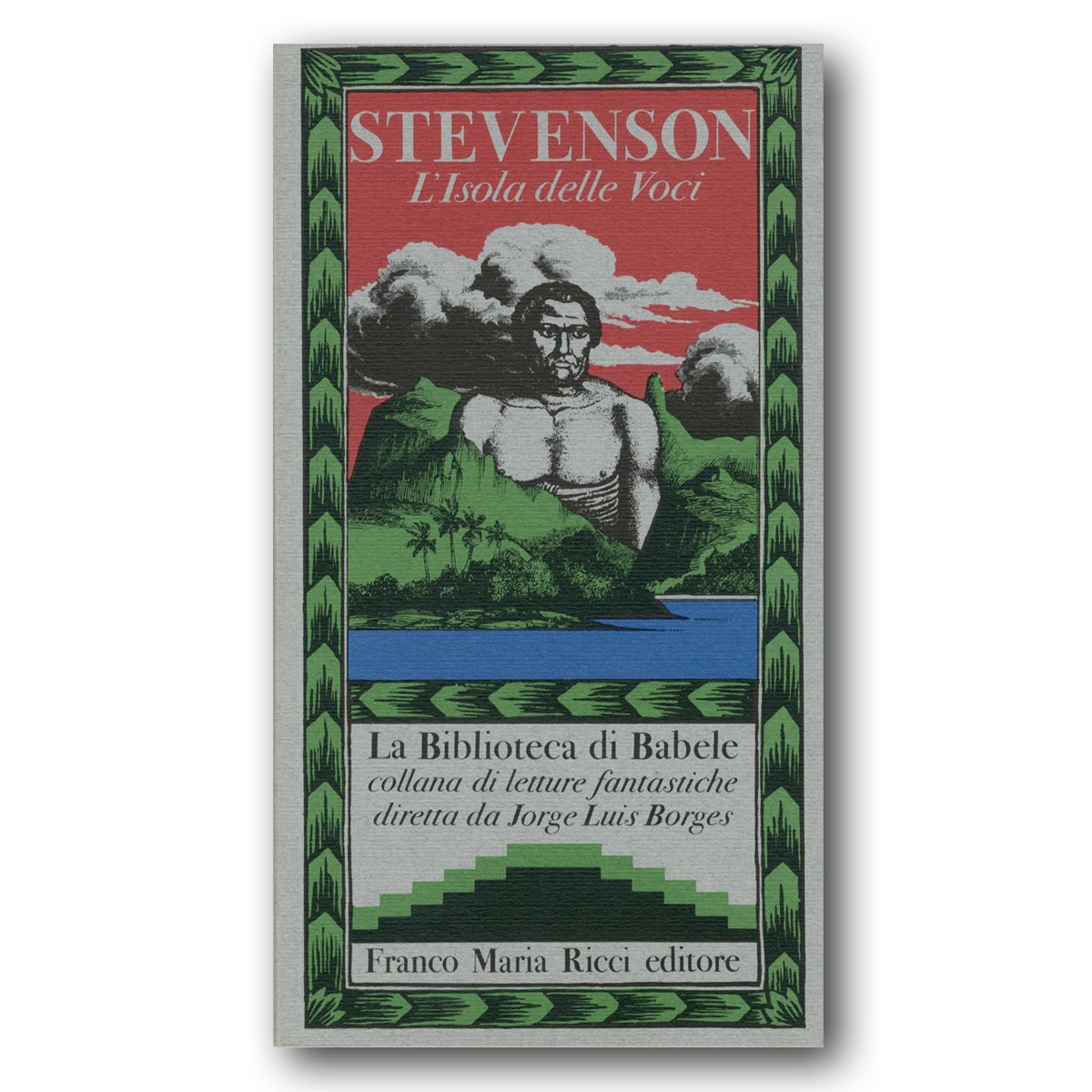

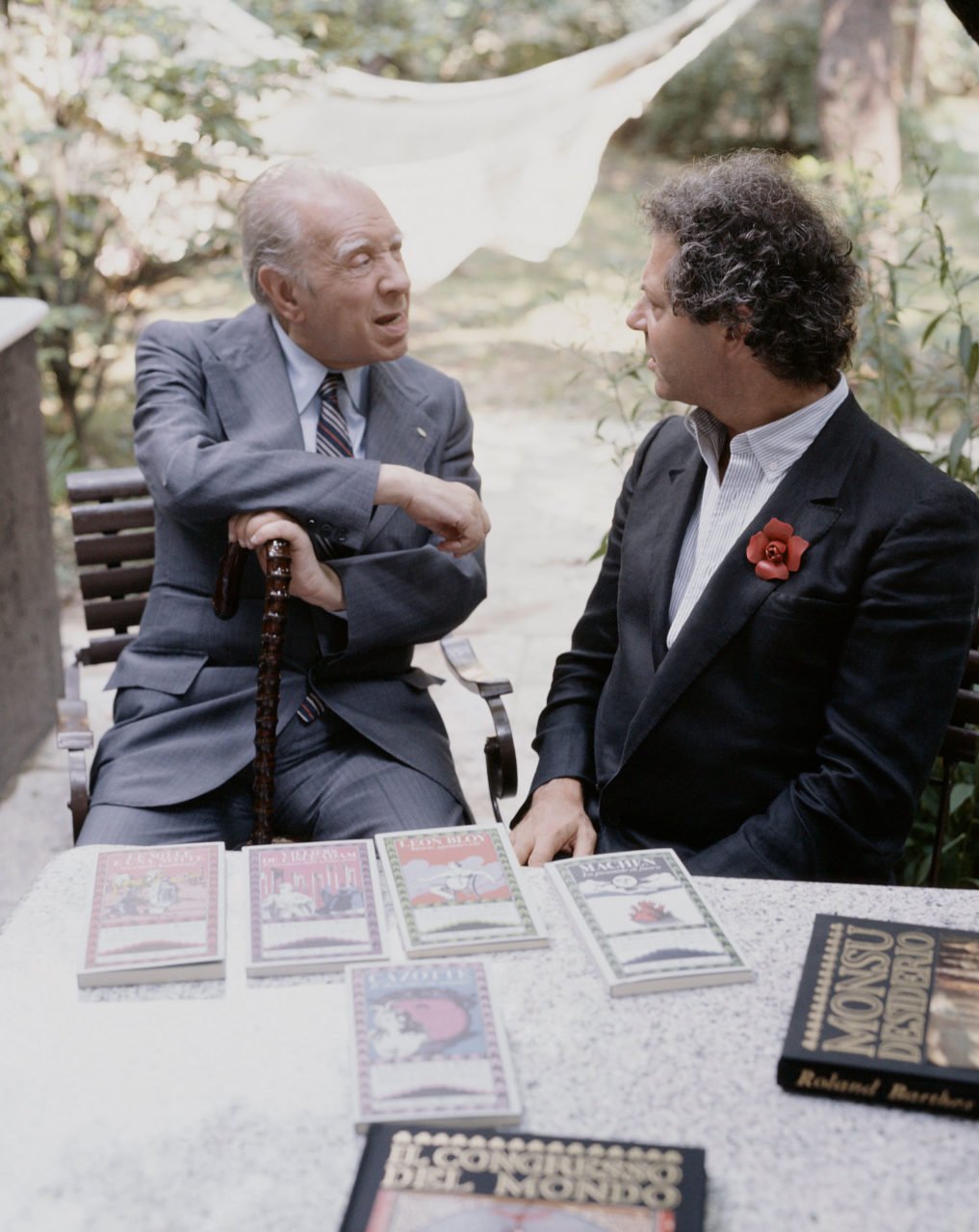

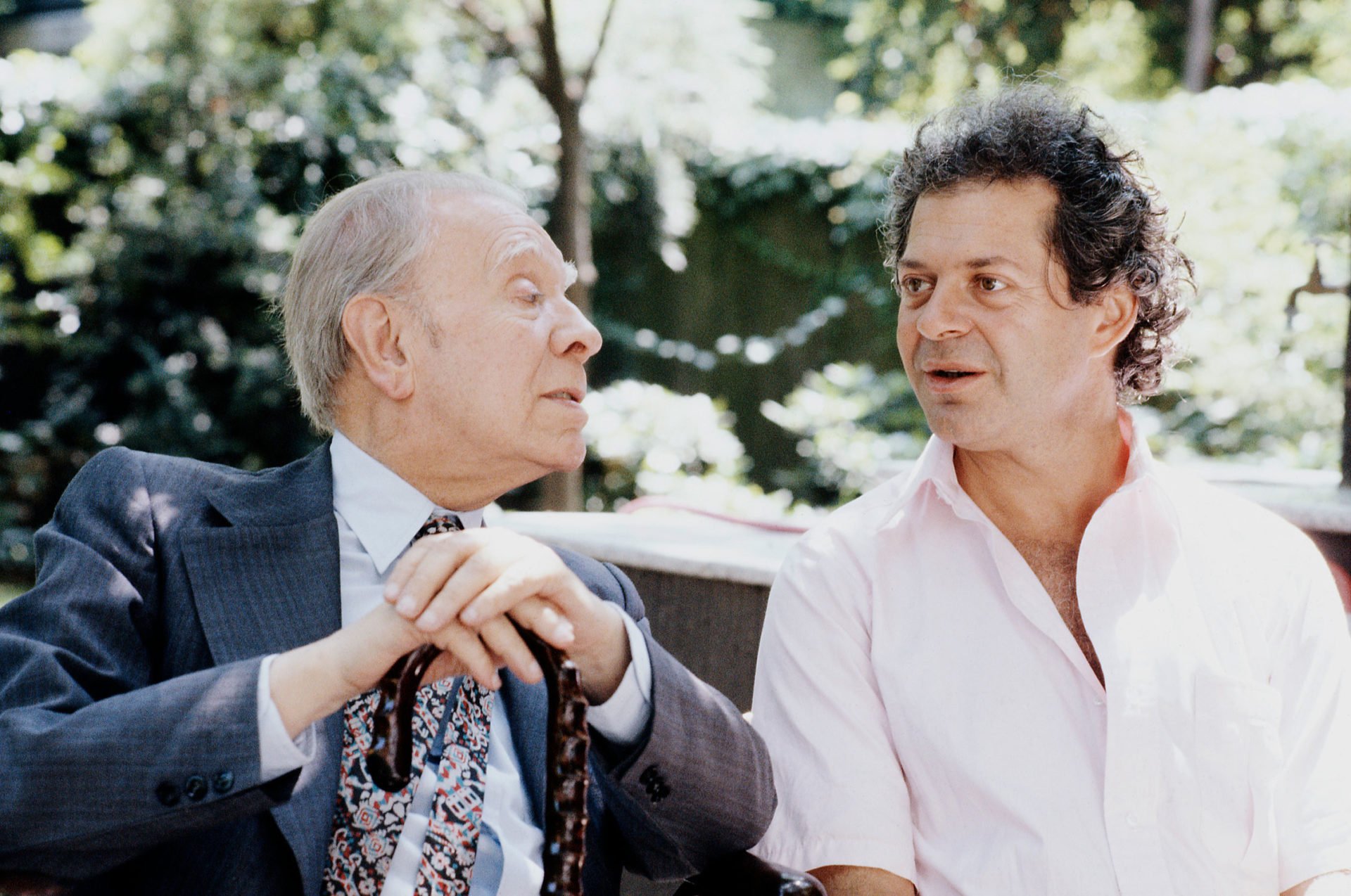

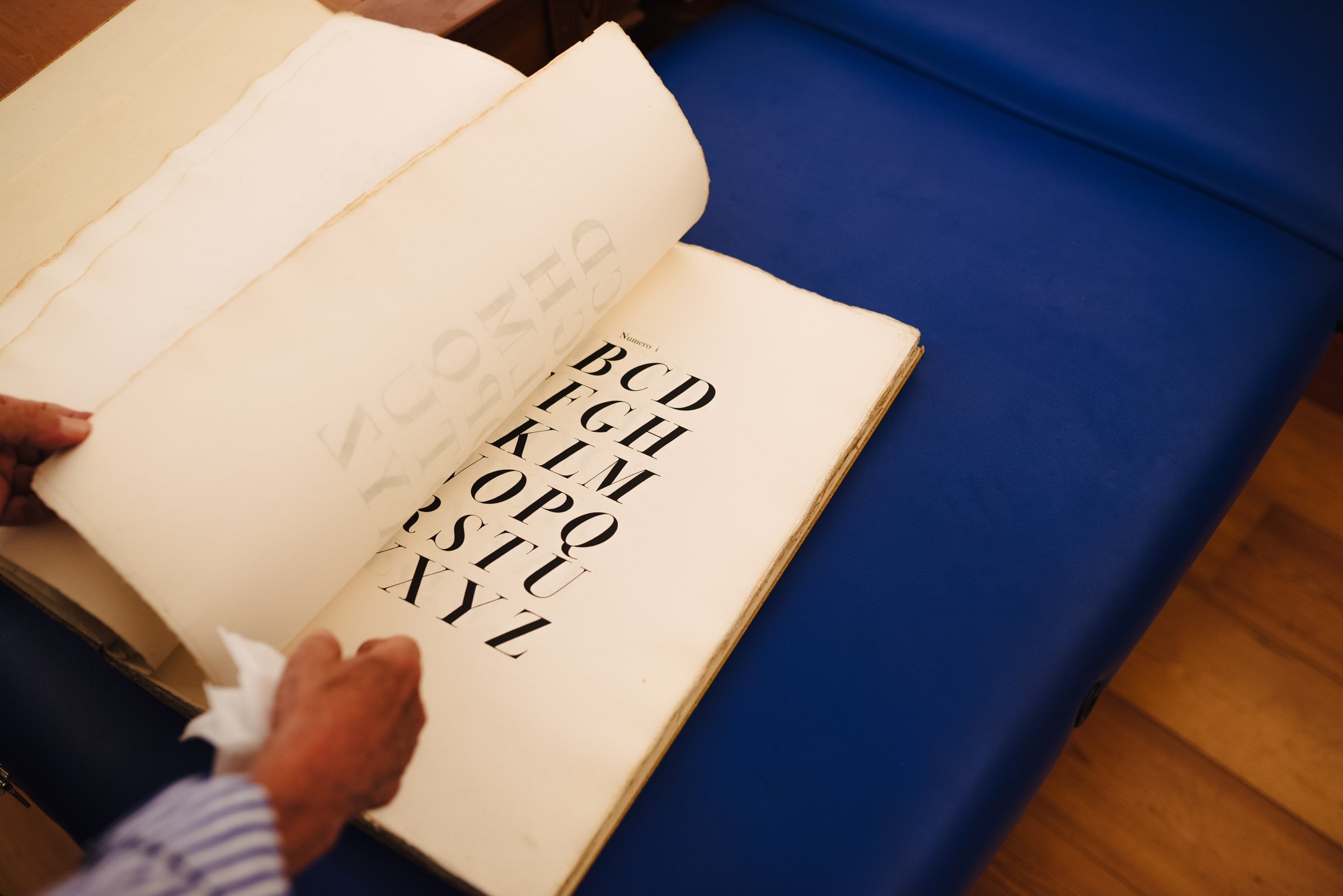

I’d been to Franco Maria Ricci’s house before. Having a genuine enthusiasm for books and the history of publishing, I harbour the deepest admiration for Mr Ricci and his endeavours. It’s simply an honour to be admitted to his splendid villa in Fontanellato, a town located in the purest countryside of the Po Valley. To the honour is added a feeling of stupor. In fact, it’s impossible not to be fascinated by this architectonic dream catapulted into the province of Parma: a bamboo labyrinth, perhaps the biggest in the world; a pyramid in red bricks giving off a mysterious and ancestral aura; a perfectly polished museum, an unusual flash of beauty; and then Ricci’s home, La Magione, a building retrieved from the depths of Novecento Italiano and launched into the future.

I always end up here in summer, immersed in the deafening sound of happy cicadas chirruping in the wind and into the blazing sun. Franco Maria Ricci, or FMR, welcomes me with that dandy air typical of those

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

close

close