This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Oiva Toikka

Interview by Ida Kukkapuro

Photography by Osma Harvilahti

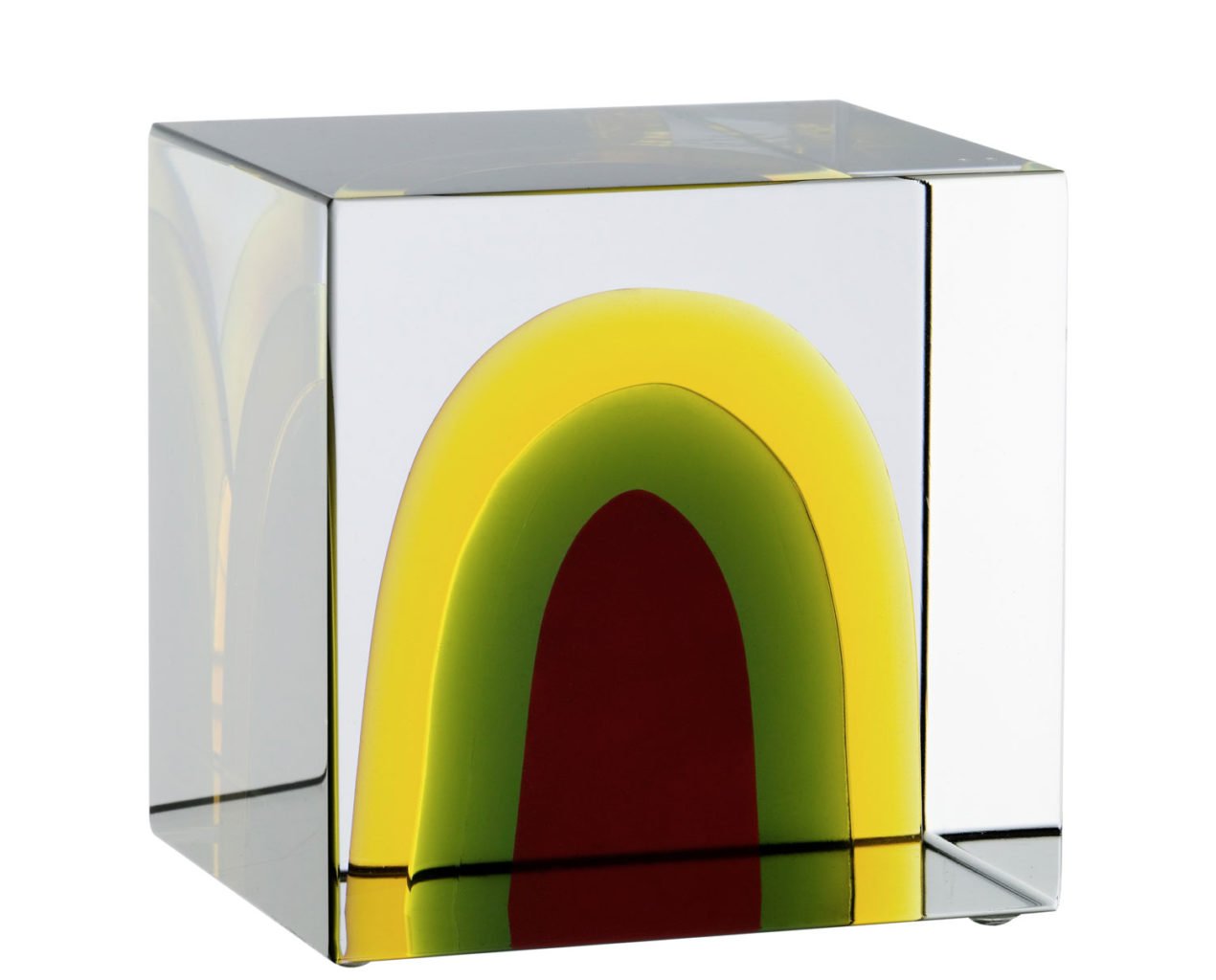

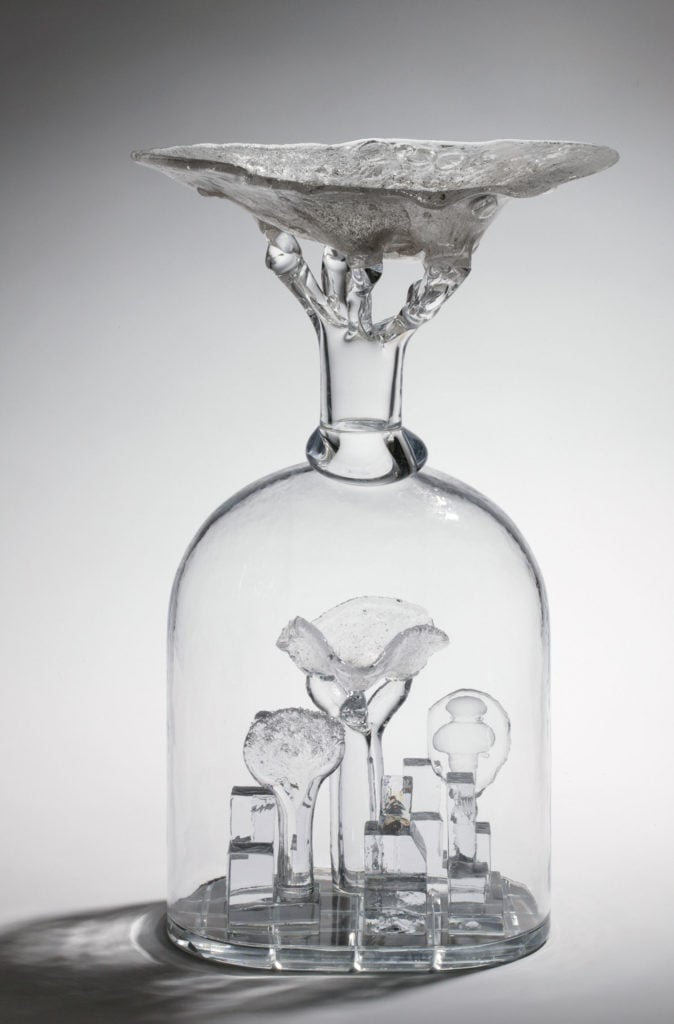

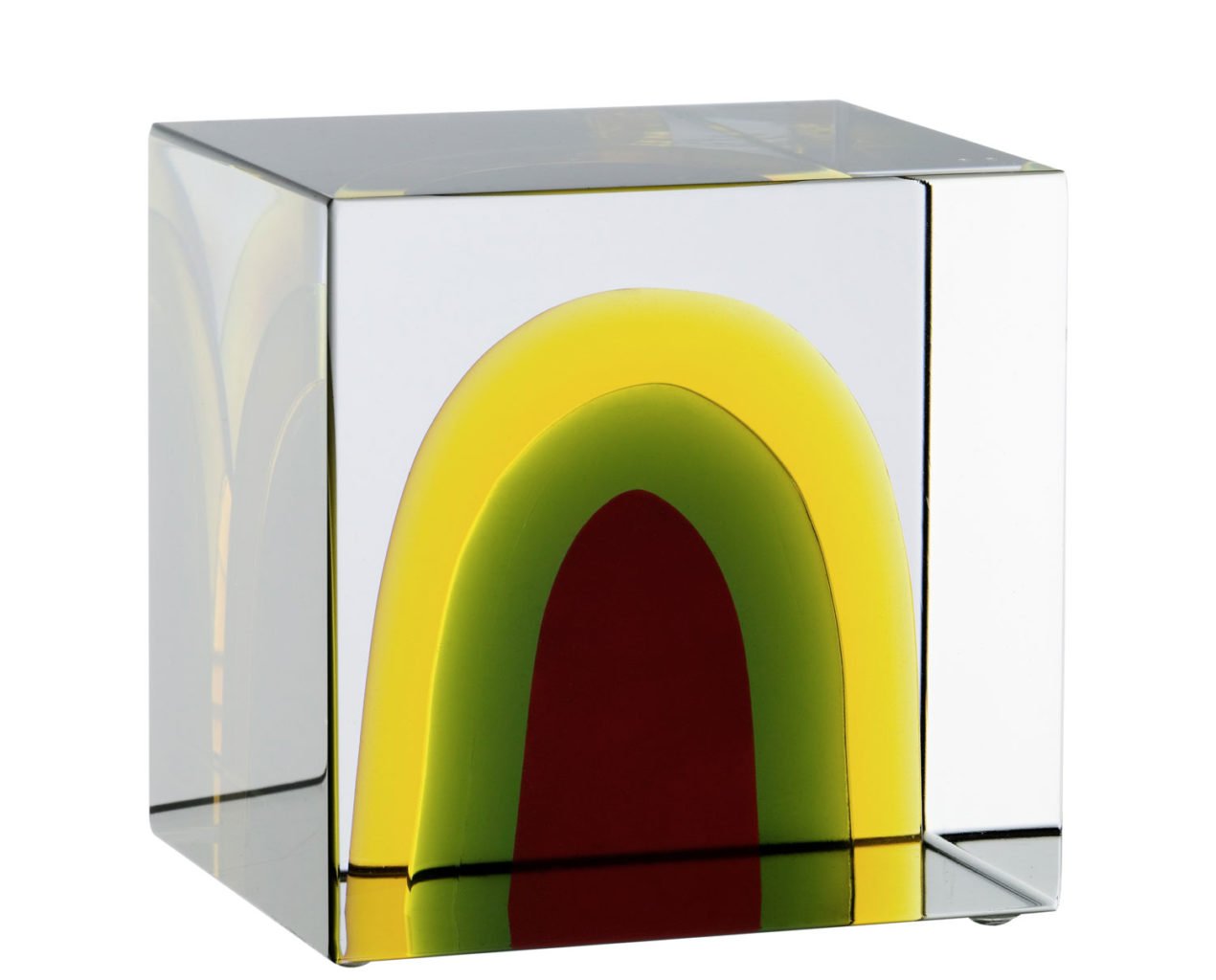

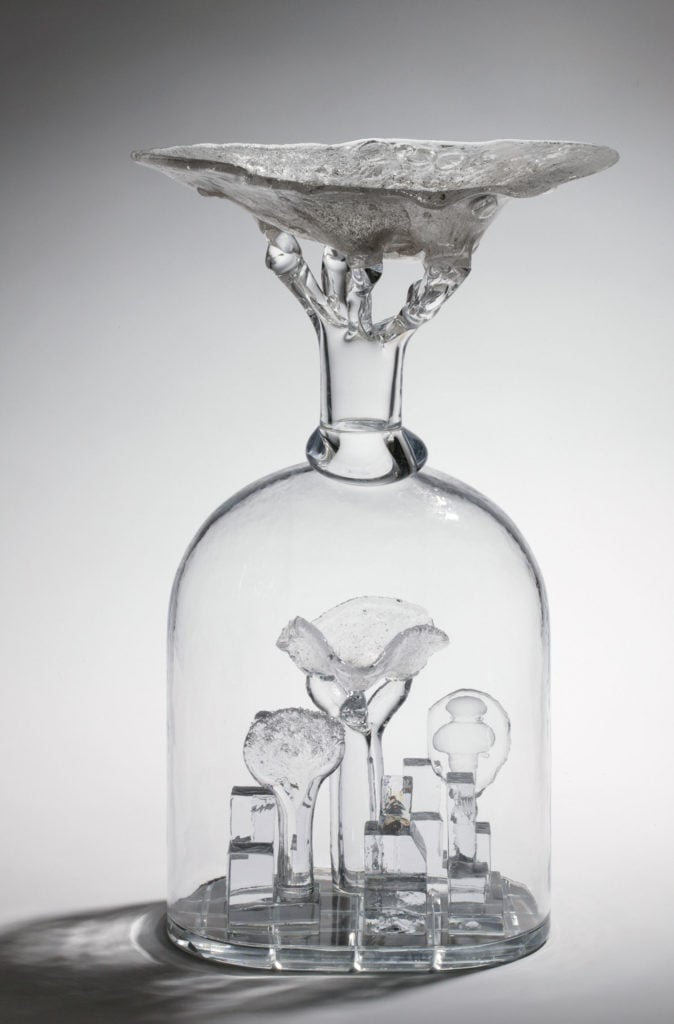

Glass designer Oiva Toikka has always worked with a smile on his face. His career started during the golden era of Finnish functional design, but he never followed the mainstream style. Instead, his path has been full of wild shapes, colours, and experiments. Toikka isn’t a perfectionist at all, but rather an explorer of form and colour. His style has even been described as baroque. Toikka’s complicated compositions, installations, glass cubes, birds, and sculptures well up from an endless imagination. He loves testing, and he especially loves it when things don’t go as planned.

Toikka’s work is at the same time easy to grasp and outspoken. In his everyday objects he brought hippie aesthetics and pop art to Finnish design. His Kastehelmi (dew drop), Flora, and Fauna tableware sets are made out of pressed glass and borrow their theme from nature. Lollipop sculptures comment directly on pop art. The award-winning artist has also worked as an art teacher in Lapland and as a set and costume designer for opera and theatre. His sets are gesamtkunstwerke, through which one can step into his playful visual world.

Toikka keeps chattering, and describes his work as blabber that has taken on a physical form. He loves teamwork for that reason: it is all about dialogue. I met the charming Toikka in his apartment in Helsinki. He lives alone but is hardly ever lonely—friends and neighbours visit him regularly. We sat at his kitchen table, steaming plates of porridge with buckthorn jam in front of us, and together explored the shapes of his past.

Let’s start from the very beginning. How did you develop such a lively imagination?

I had a wonderful childhood. I come from the countryside, a small Karelian village [eastern Finland, now part of Russia]. There were an awful lot of kids, and we used to gather at our house. There was always a lot going on. My parents were creative but they weren’t artists. My father was a soft-spoken farmer, and my mother a perky housewife. I think they were high-quality people.

Was your creativity already visible then? When did you start creating things?

I was eight years old when the Russkies attacked and the war started. Then came this one winter when my sister and I couldn’t attend school. We were completely free. I started drawing with a girl from the neighbourhood. First it was copying—I copied postcards. Then at some point I started making my own images.

You studied ceramics at Ateneum in Helsinki, when it housed the School of Applied Art. Why did you choose that field?

I wanted to study graphic design, but I didn’t believe I would get in. So I chose ceramics. Later they would have accepted me, but my teacher wouldn’t let me go, since there were so few men in the ceramics department. Those were brilliant times! Our department was like the heart of the school—we didn’t have to change teaching rooms like all the others. And all the other students came to visit us. I was as poor as a church mouse. Still, somehow I made it. I was quite hard working, but my ceramic pots weren’t that great. Then I started making more sculpture-like things.

You didn’t follow Nordic functionalism. How come you were so brave and why did you dare to be different at such an early stage in your career?

I was frank. I had no inhibition. It also helped that others supported me and appreciated what I did. It encouraged me to continue on my path. I made this and that from ceramics. My teacher was great and supportive, too. People considered me to be gifted, which I still don’t really get. I was never any virtuoso. Just very inquisitive.

Where does your visual language stem from?

My creations are the same as my chatter. I babble constantly, and making is the same, just in physical form. I have also worked with lovely materials, ceramic and glass. They inspire me.

What happened when you gave up ceramics for glass?

I acquainted myself with glass during my second year at Ateneum. Kaj Franck and Saara Hopea came up with the idea of inviting students to the Nuutajärvi glass factory. There we got to try the new material. They invited my wife, Inkeri, Vuokko Nurmesniemi, and me. Vuokko was already working by then. She is excellent. We are close friends.

Ceramics and glass are both marvellous materials, and looking at their metamorphosis is fascinating. Has the material guided you?

I may have been more guided by teamwork, which I have always loved. Glasswork is always a group effort. I never learned how to blow, and then later I had back problems and couldn’t have done it. I have never been fit, I’m something of a lazybones. Glassblowers are highly involved in the creative process, and way more ambitious than me. When a tiny mistake happens blowers are always throwing experiments away. I would always yell, ‘Don’t trash it!’

I’ve heard your studio was filled with these flops. Why did you keep them?

From those pieces you can learn the most. There is always an idea that can be worked on. I trust in accidents and misunderstandings. The glassblower might not catch what I mumble, and the work can turn out better than the original idea. It’s fruitful teamwork. My words aren’t law. It’s just about decision making, deciding which lead to follow.

How does this collaboration work in practice?

By talking to one another. Someone always takes the lead and then the process will advance. One person sketches something and then others improve it. I didn’t collaborate much with Kaj, just a few unique pieces. He had a temper—and he could let it show around me because we knew each other so well. We always talked about everything, so our language wasn’t that formal. Once he asked me to do something, and I said no. He got mad and said, ‘You devil’s shitface, go to hell!’ I told him again, ‘No’. That was the typical looseness in our relationship.

Your work was totally different to Kaj Franck’s, though you were really close. What did you talk about with him?

We shared a desk, sat face to face. There we drew, sketched, and squabbled. The conversation was very important. We talked about everything, it was very open. He did not stick his nose into my work—he could have done it more, but he was very considerate. In his own work he was precise; if he wanted something to be a certain way then that’s how it was done. He made such great objects for everyday use.

So you collaborated mostly with the glassblowers. How did that work?

Each and every tiny thing is a result of collaboration. First one version is made, and then you’ll see if the colour needs to be changed. Blowers work according to their skills, and suggest what can be done and what cannot. For me it’s typical to change my opinion quickly. Glass is so flexible and brisk that your thinking needs to be, too. I have never found sketching that important. You need to get a 3D model to be able to develop the work.

When you worked for Nuutajärvi glass factory, your family also lived in the Glass Village located in the middle of the forest. How was your home life there?

When we moved there in 1963, it was a sizeable town, almost like a small city. The population was 600. We lived in the apartment of my predecessor, Harry Moilanen. The house had two apartments, and Kaj Franck lived in the other one. So we were next-door neighbours. In the beginning when my wife wasn’t yet working, Kaj used to dine with us; the kids in the village thought he was my sons’ grandfather. Nuutajärvi was exciting and a fine environment to work in. The glassblowers and Swedish-speaking factory managers lived there, too. It was like a huge family.

What was your home like at Nuutajärvi?

We have three sons and, as in my own childhood, there was always some hullabaloo going on. There were a lot of visitors because of Kaj. Through him I also got to know other colleagues. Many of the guests were young. Kaj didn’t consort with his peers, like Tapio Wirkkala and others. Once a graphic designer, Kari Ropponen, paid a visit but the doors were locked. So he slept overnight on Kaj’s terrace, waiting. Another time Kaj went travelling and left his front door open for two weeks. Everyone in the community understood him.

Was your work visible at home?

In a way. I used to bring things home to ponder and look at. After some time, Inkeri told me to take the junk away. She wasn’t pretentious. She spoke her mind and didn’t aim to please.

You have since worked with nearly all the big Finnish design companies: Arabia, Nuutajärvi, Marimekko, Iittala, Fiskars. What do these firms mean to you?

Changing from one firm to another was like moving from your homeland. It has been tough delving into a new company, not to mention learning how to love them. And sometimes it would have been better not to. There have been some bad managers making bad decisions—now Iittala has purchased Nuutajärvi, and I think it’s a catastrophe. It was the finest and oldest glass factory still in operation [in Finland], and it worked so well on its own.

Have you made a lot of compromises?

I have. I am not at all unconditional. I have told myself that if it doesn’t work this way then it might work that way. There is always a way. I think the same about copying. If my work is copied meritoriously, I’ve continued my work and made new pieces.

Have you been copied a lot?

It has happened. Kastehelmi [one of Toikka’s most popular designs] was copied by a British company. Then they applied for exclusive rights in Britain. In our original middle-sized plate there is a technical flaw, and they copied that, too! That’s how they were caught and forced to stop. In Italy they copied Flora. The Italians didn’t produce the biggest plates and pitchers, since the mould was very expensive, but they were sold at Bloomingdales: on the shelves there were glasses from Italy and big plates from Nuutajärvi. But they went down at some point. We didn’t sue them.

In addition to glass you have worked a lot with opera and theatre. Tell me about your set designs!

Did you see the Orlando Paladino?

No. The premier was 15 years ago and I was still a kid. I’ve seen pictures though!

That was the best of them, a real treat. The actors were so unreserved and gorgeous. But the Finnish National Opera won’t do it again. It was such an expensive production.

When working on a set, where do you start?

We sit and have a cup of coffee with the director, Lisbeth [Landefort], and start chatting. I doodle on the napkins and when the coffee is finished she collects the napkins. Then later she suggests an idea from one of those drawings. It’s great to work with her.We are very equal; she doesn’t want to control every detail. When working on a piece, we have small meetings continuously and come up with new details.

You have also designed costumes. How is that?

The most important thing is whether the actor accepts the outfit. If you are the protagonist and don’t feel at home in your costume, it is a catastrophe. In that case I make something new. And I won’t stress about it. It’s impolite to make unsuitable clothes; they are so close to the skin. After designing sets and costumes, I’ve come to the conclusion that clothes are way harder to make. Wearable items need to work perfectly in three dimensions. With both sets and costumes, I always look at what can be reused. It’s the same with glasswork; I have even used other designers’ moulds and revised them.

Which line of work has been the most enjoyable?

I couldn’t say, it has been full of laughter, all of this. I have always enjoyed myself. Not always laughed out loud, but at least had a smile on my face. It’s especially important for me that other people enjoy themselves as well.

Has rationality ever come first?

Sure. But I wouldn’t claim those pieces to be my most successful works. Oh, dear, so many things have fizzled out. A lot fits into a large body of work. But then there are my Kastehelmis, too.

Yep. That wall plate behind you is one of my favourites.

They are from my catastrophe series. That one is called Flood, the other is Fire. Catastrophes are beautiful, when one is not in the middle of them.

In your work you have commented on your environment and topical themes. Why?

Current events inspire me. I also have a tendency to fall in love with sayings or phrases that I bump into. Right now I am fond of the name of the ballet La Fille Mal Gardée [The Wayward Daughter]. I want to make it into a mosaic.

You have made glass birds ever since the 1972 Flycatcher. They are really popular. Have you ever gotten tired of the annual Iittala birds?

Well, when the birds are out there, I find them wearisome. Once I start working on a new one though, it gets better. When the blowers are happy too, then something good comes out. The 2015 bird is a bean goose, Lakla. It comes from a poem in Kanteletar, a collection of Finnish folk poetry.

From Nuutajärvi, you moved with your late wife to Hakaniemi, in downtown Helsinki. Are there any village-like features there?

Sure. Should we invite my next-door neighbour Elma here at once for a cup of coffee? She visits me often and we have supper together. Before, I had daily porridge at the market place, but now my legs are not that good anymore. I have a lot of guests and I enjoy it. It’s an inherited tradition from my hometown. There the bus stop was next to our house, and everyone coming and going would pay us a visit. My mother invited them all to the dining table, even if it wasn’t that big.

Do you still work a lot?

I get enquiries non-stop. I am planning a trip to Italy, where I work with Magis. And there is a solo exhibition at Forsblom Gallery in Helsinki later this year. I plod along. It’s half bustling about and playing, but never mind that. At least there is something to do.

This interview with Scandinavian glass art designer Oiva Toikka, was originally featured in Apartamento issue #14, back in 2014. Oiva passed away at the age of 87 this past April 22, 2019. Our thoughts and condolences go out to his family and friends.

close

close