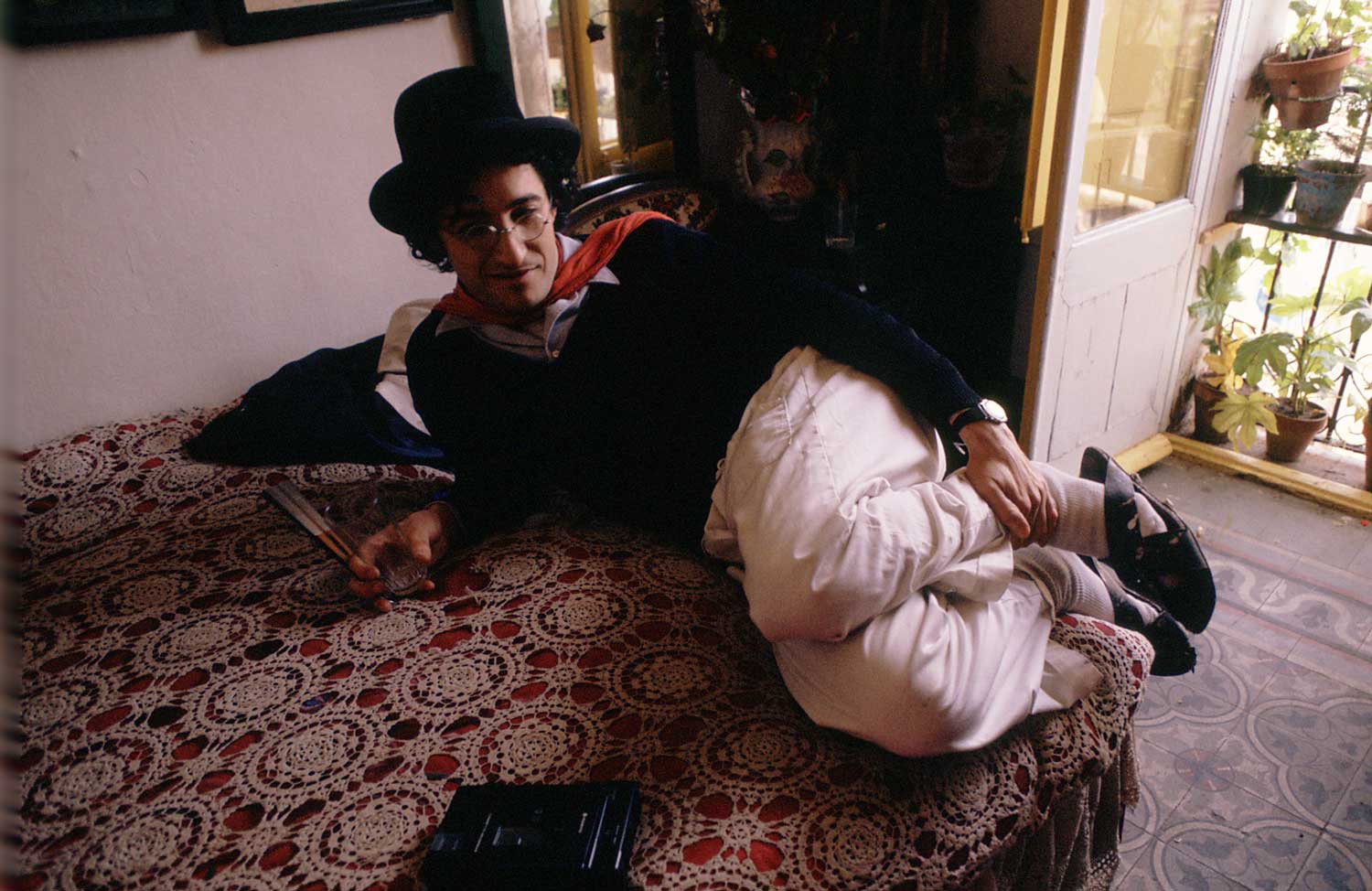

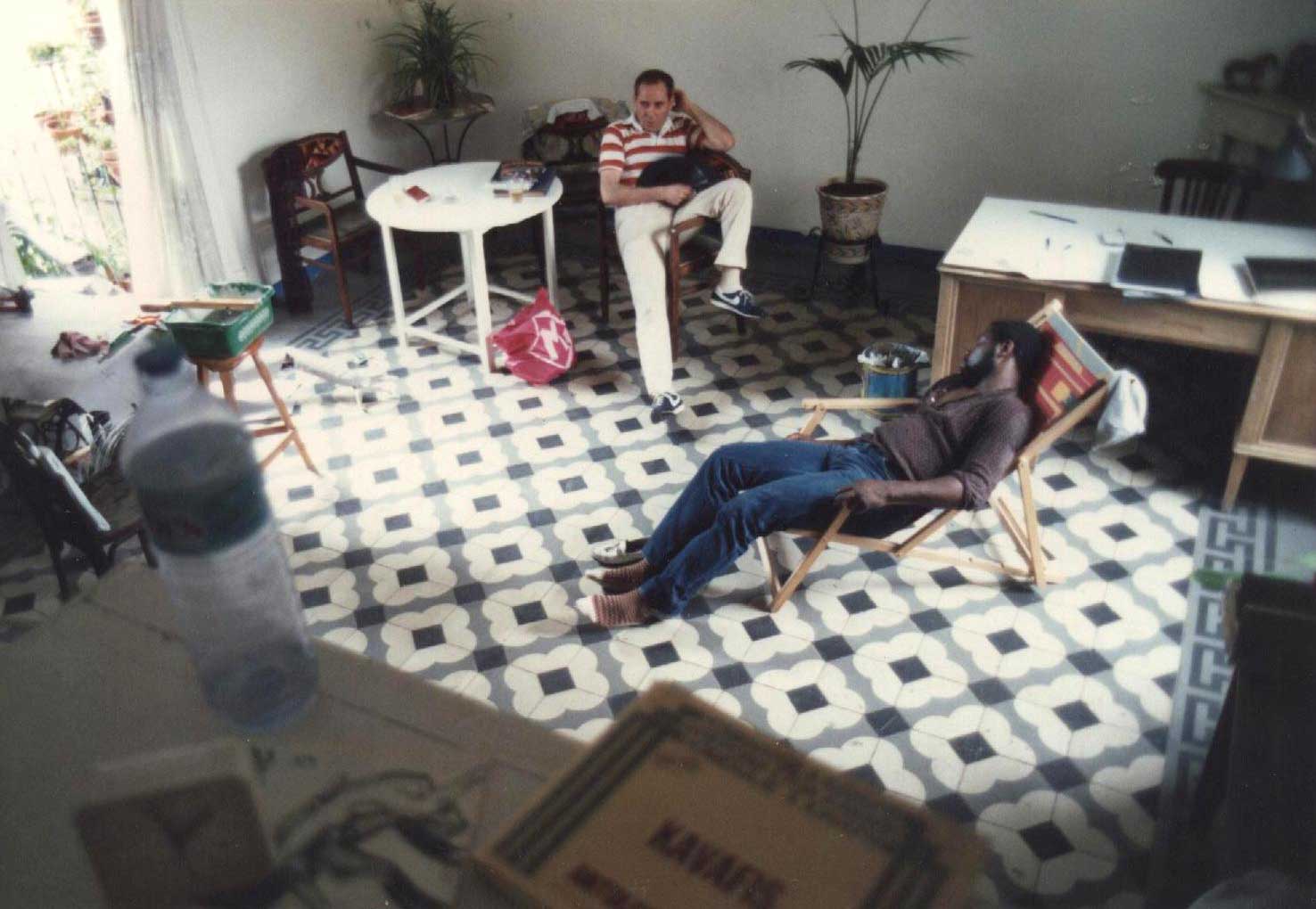

In the ‘70s, number 12 Plaza Real (where Nazario still lives today) was almost as popular and eccentric as 13 Rue del Percebe, which, for those who might not know, is the unique building that gives its name to and illustrates a series of comic strips from the ‘60s, created by Francisco Ibáñez. Its peculiarity is that it doesn’t have a façade, leaving exposed the interiors of all its apartments and the ludicrous adventures of all the neighbours living therein.

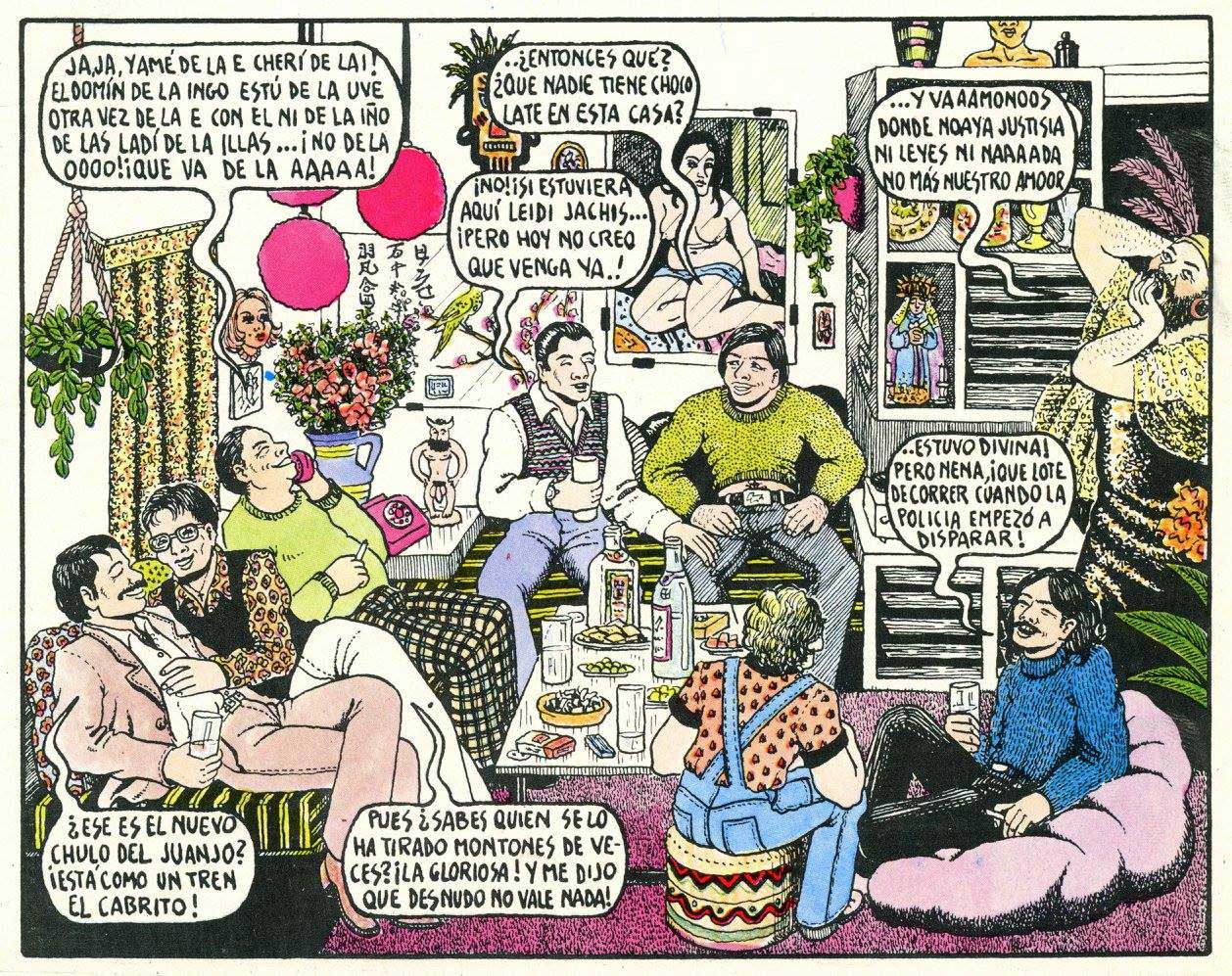

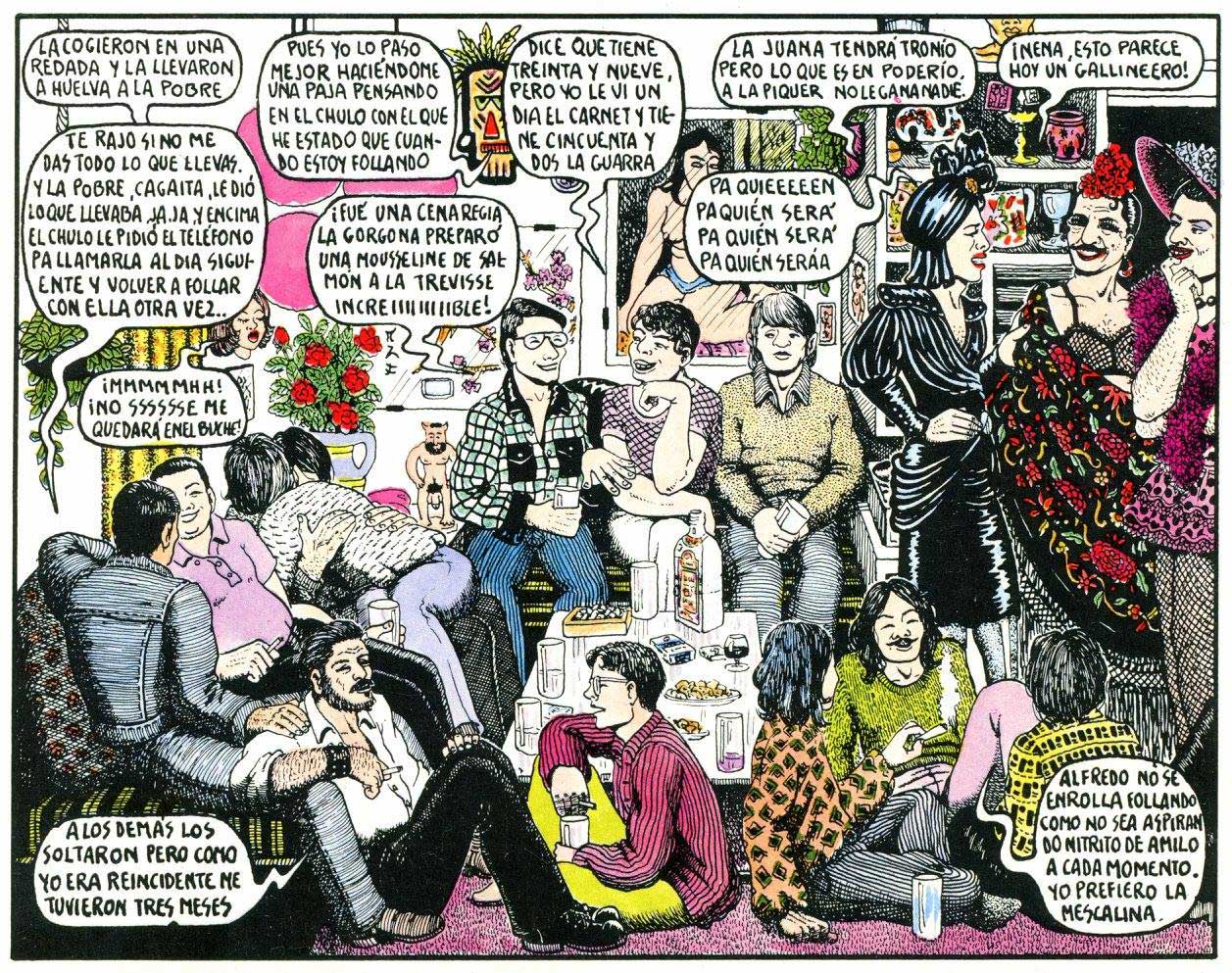

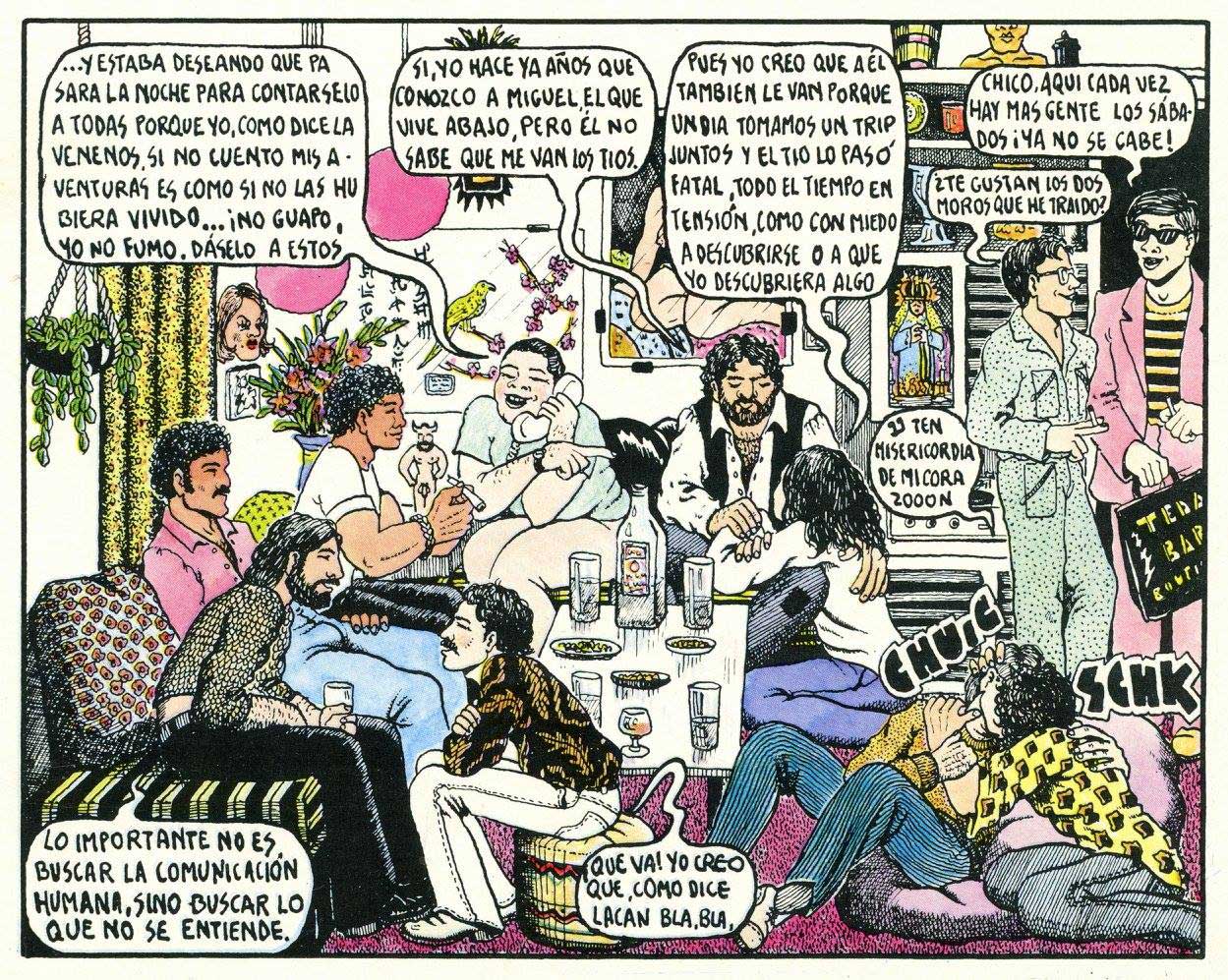

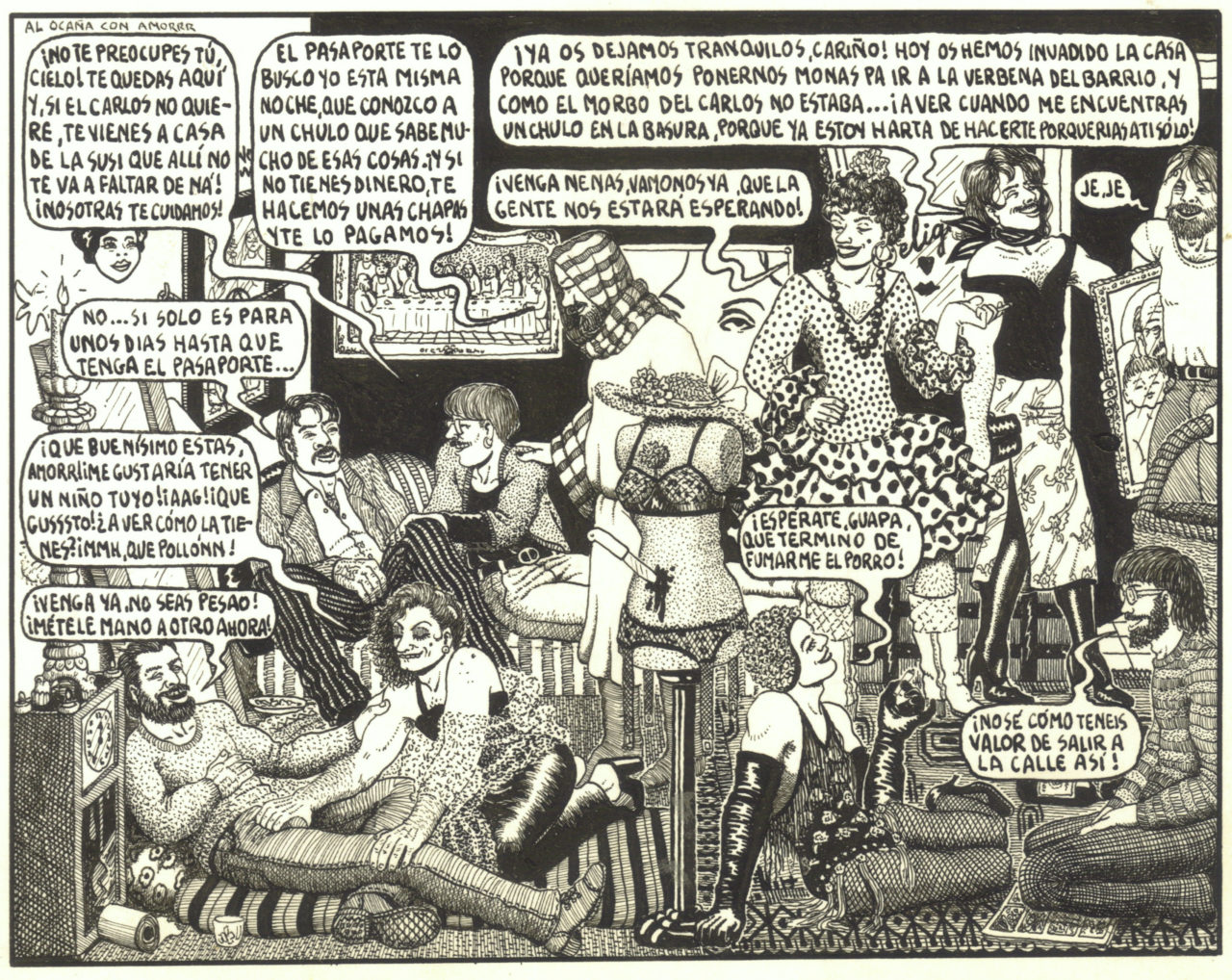

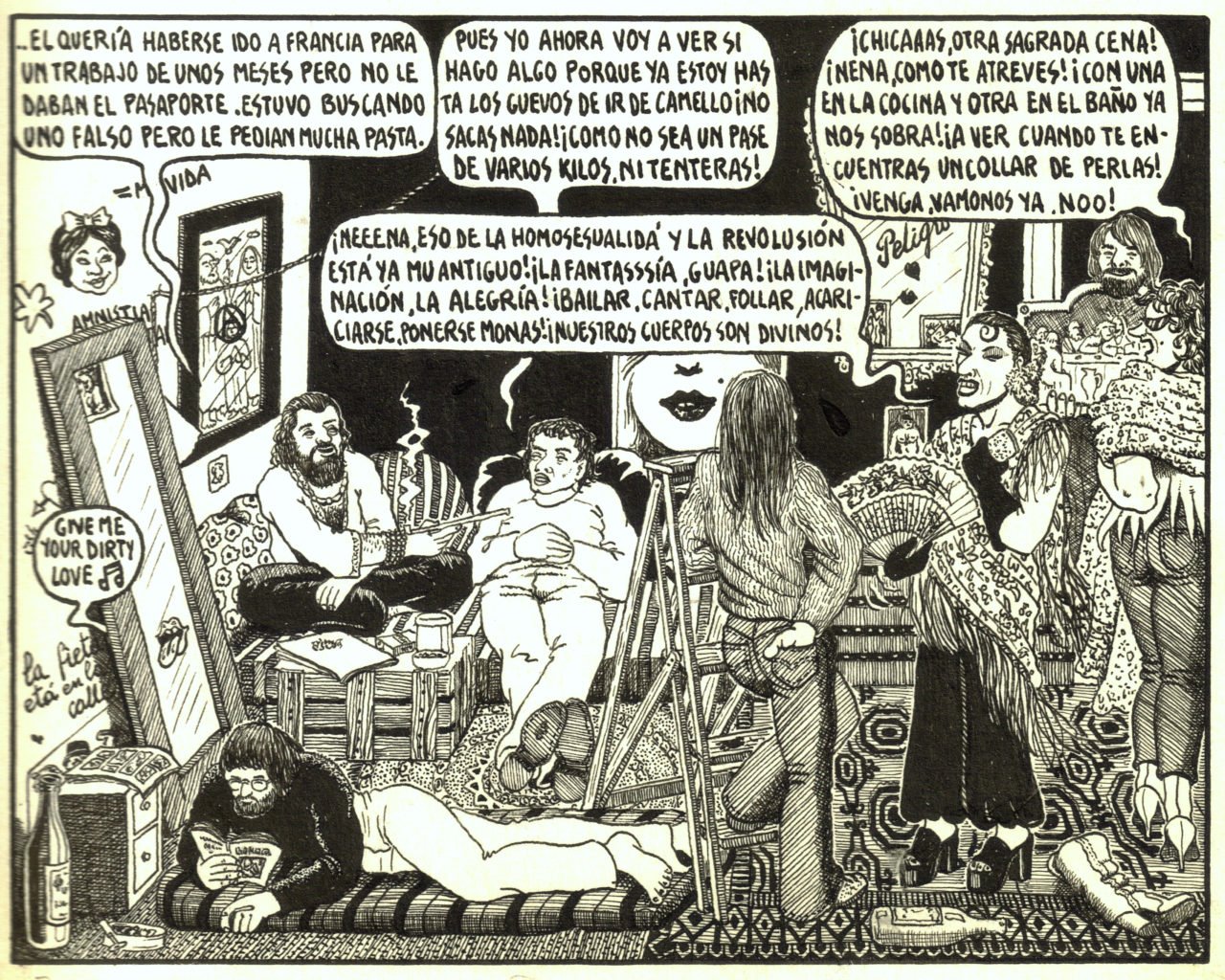

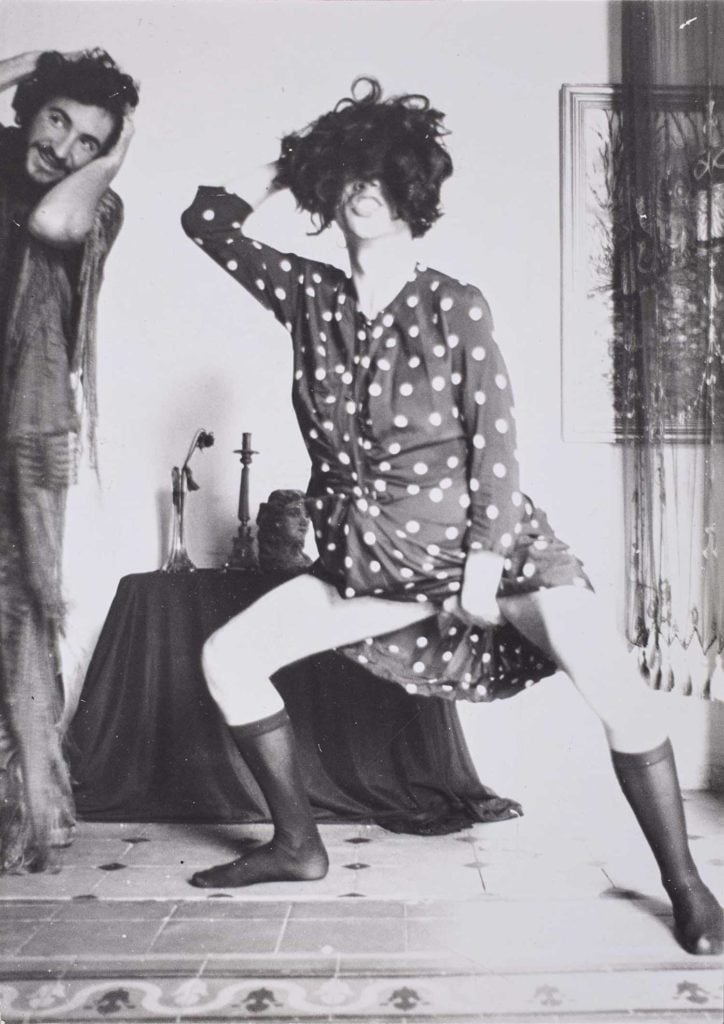

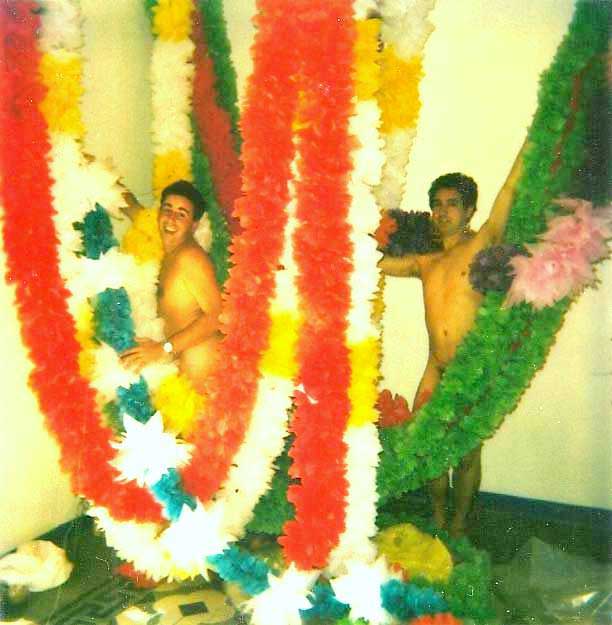

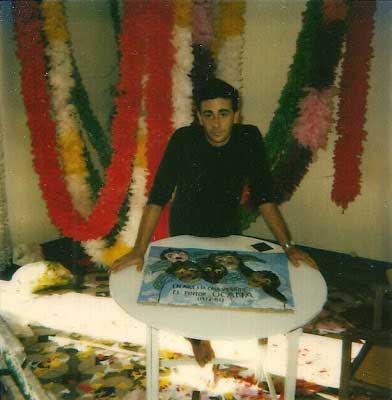

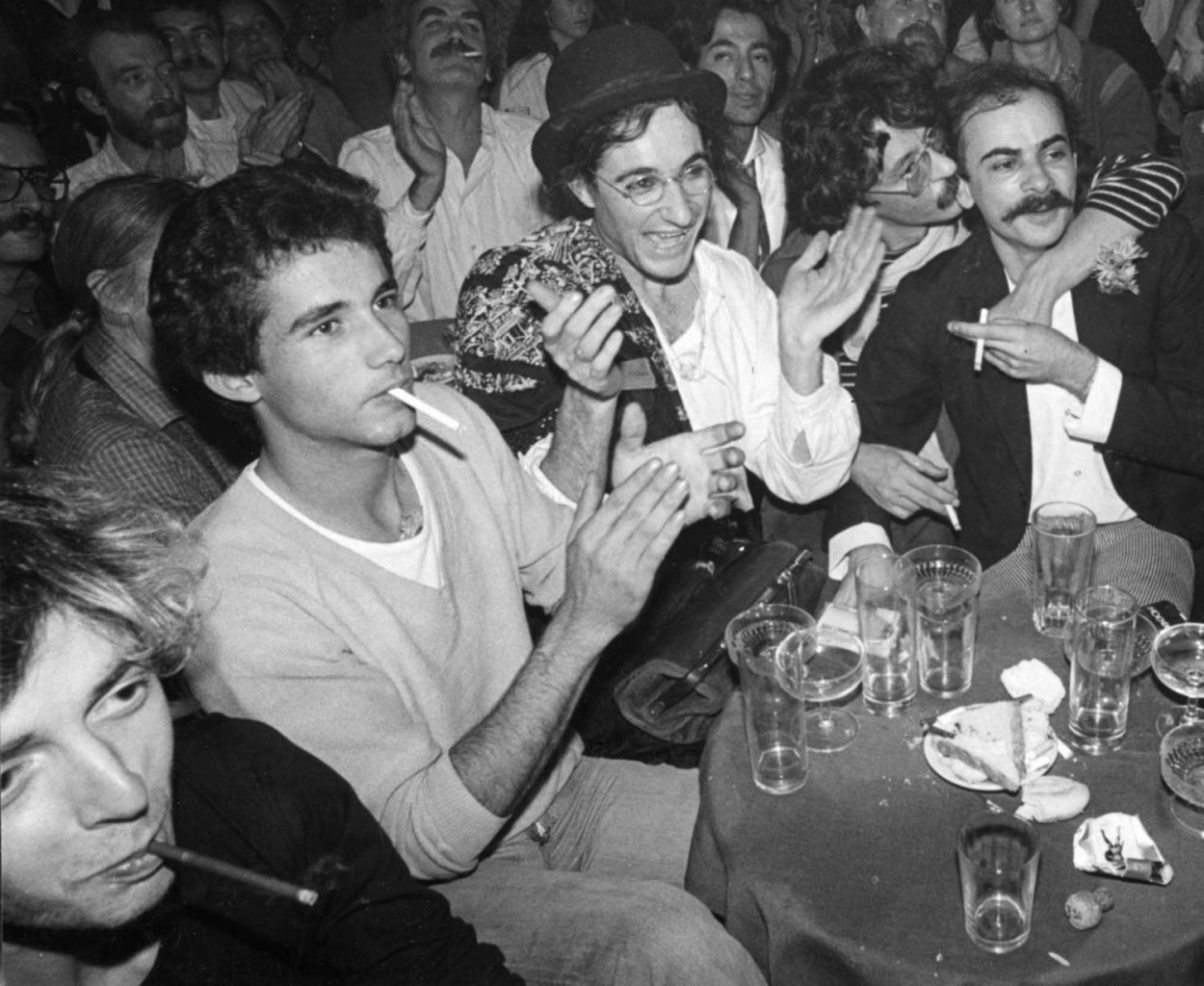

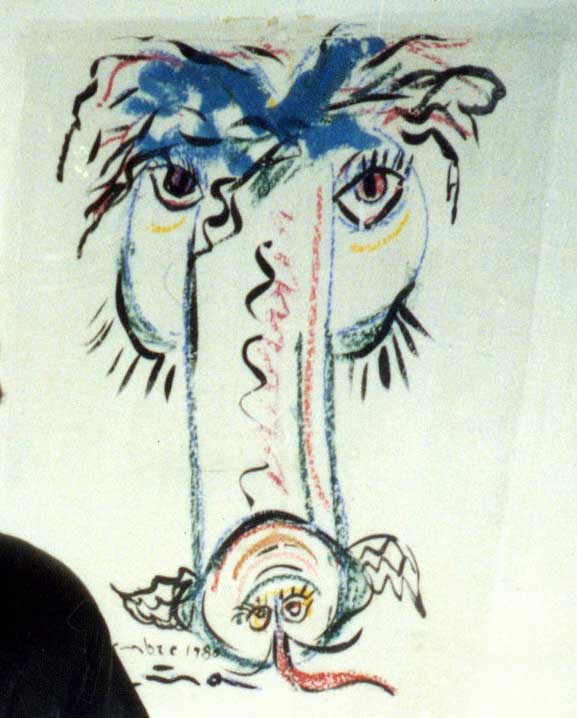

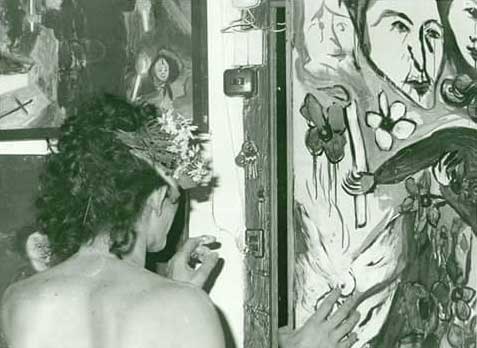

The initial comparison comes to mind because, at the end of the ‘70s, Nazario reworked this idea of using the cross-section of a building in his comic Los Apartamentos La Nave, and at the beginning of the ‘90s he pushed it even further, ‘to the extremes of mariconeo’ (in his own words) in Ali Baba and the 40 Maricones. But, to be clear, the two apartment blocks reproduced in these comics are not number 12 Plaza Real, nor do they feature the real tenants who passed through the various storeys over the years. (In his books Plaza Real Safari and La Vida Cotidiana del Dibujante Underground, Nazario evokes the strange nuns from the nursing home of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church and the Hare Krishna temple worshipers on the mezzanine; the world-renowned flamenco dancer who’d fallen into obscurity and was sheltered by two old bourgeois women—a mother and her spinster daughter—on the ground floor; the diverse guests from the hostel, mostly Black people and Moroccans, on the first floor; and so on and so forth.) But what is reflected (especially in Ali Baba) is this crazy desire to live and to fuck that was so much a part of the ‘70s and so little a part of the ‘90s (due to the ravages of AIDS), that general state of excitement that reigned on the second floor, where Ocaña and all the others exuded youthfulness and pheromones.

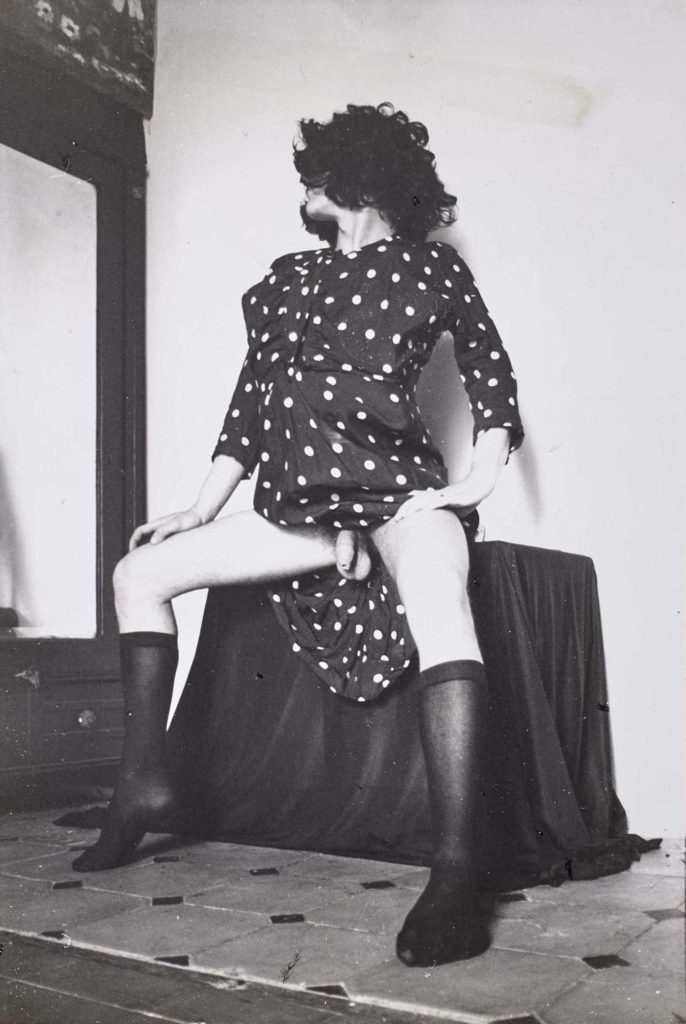

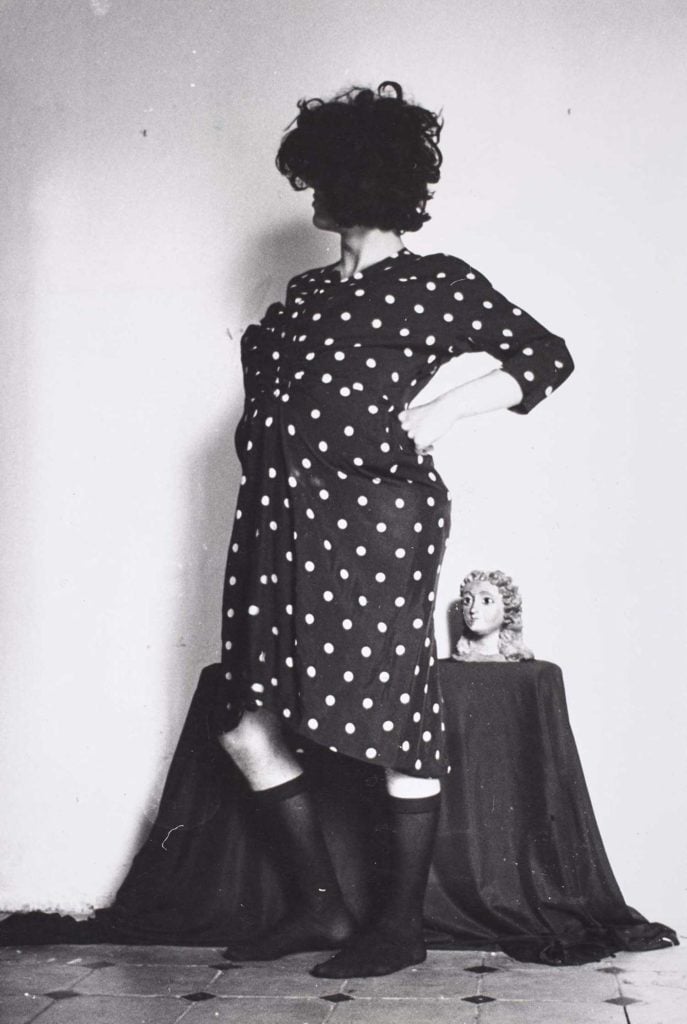

Leaving aside these macro vignettes, it’s easy to imagine (like in an ensemble film by Robert Altman, Luis García Berlanga, or Adolpho Arrietta) a long sequence shot filmed down the U-shaped corridor that joined the eight studios on the second floor, with a mess of cast members acting like flaming fags, coming and going, in and out, from here to there, revolving around Ocaña, the only star protagonist of number 12 Plaza Real:

close

close