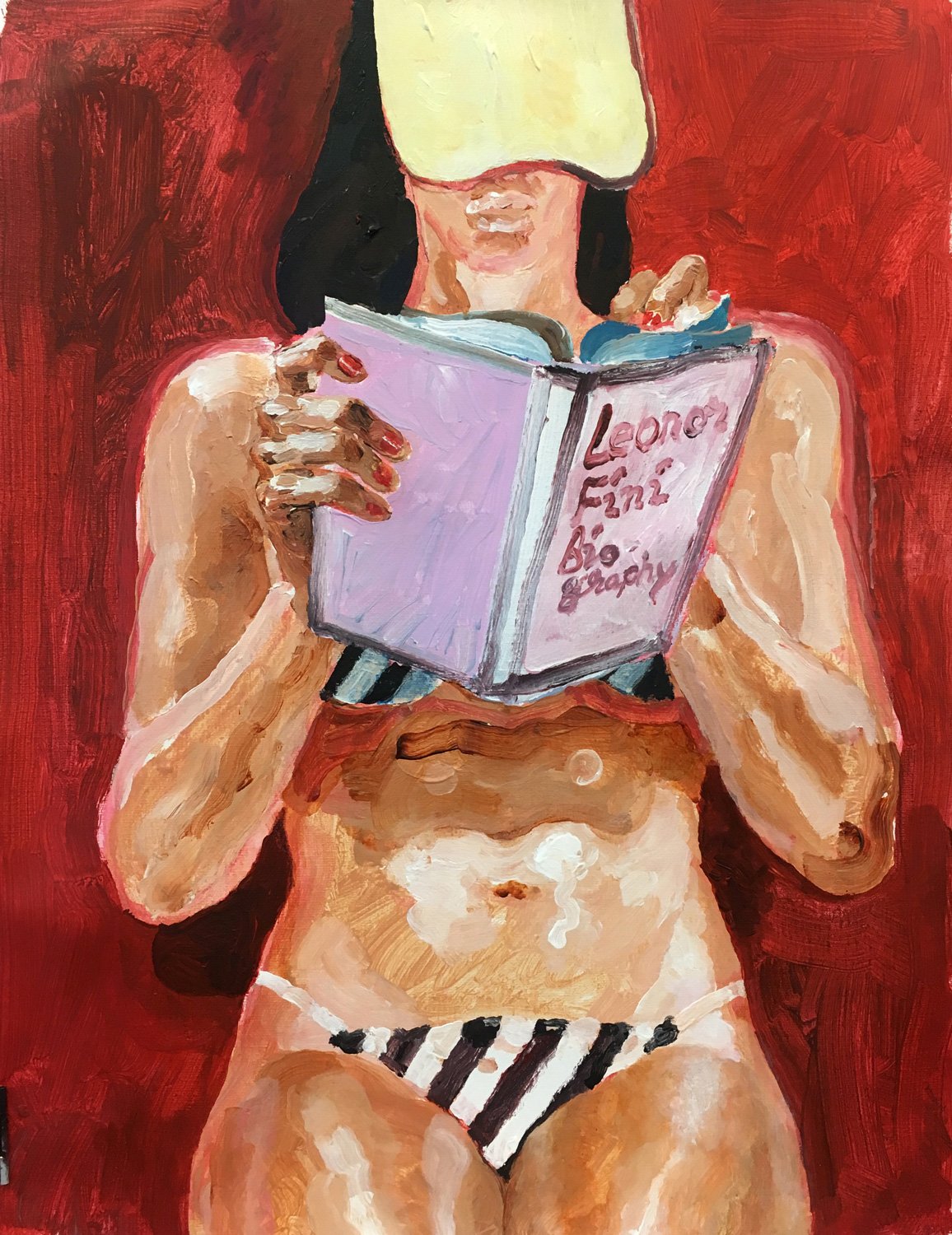

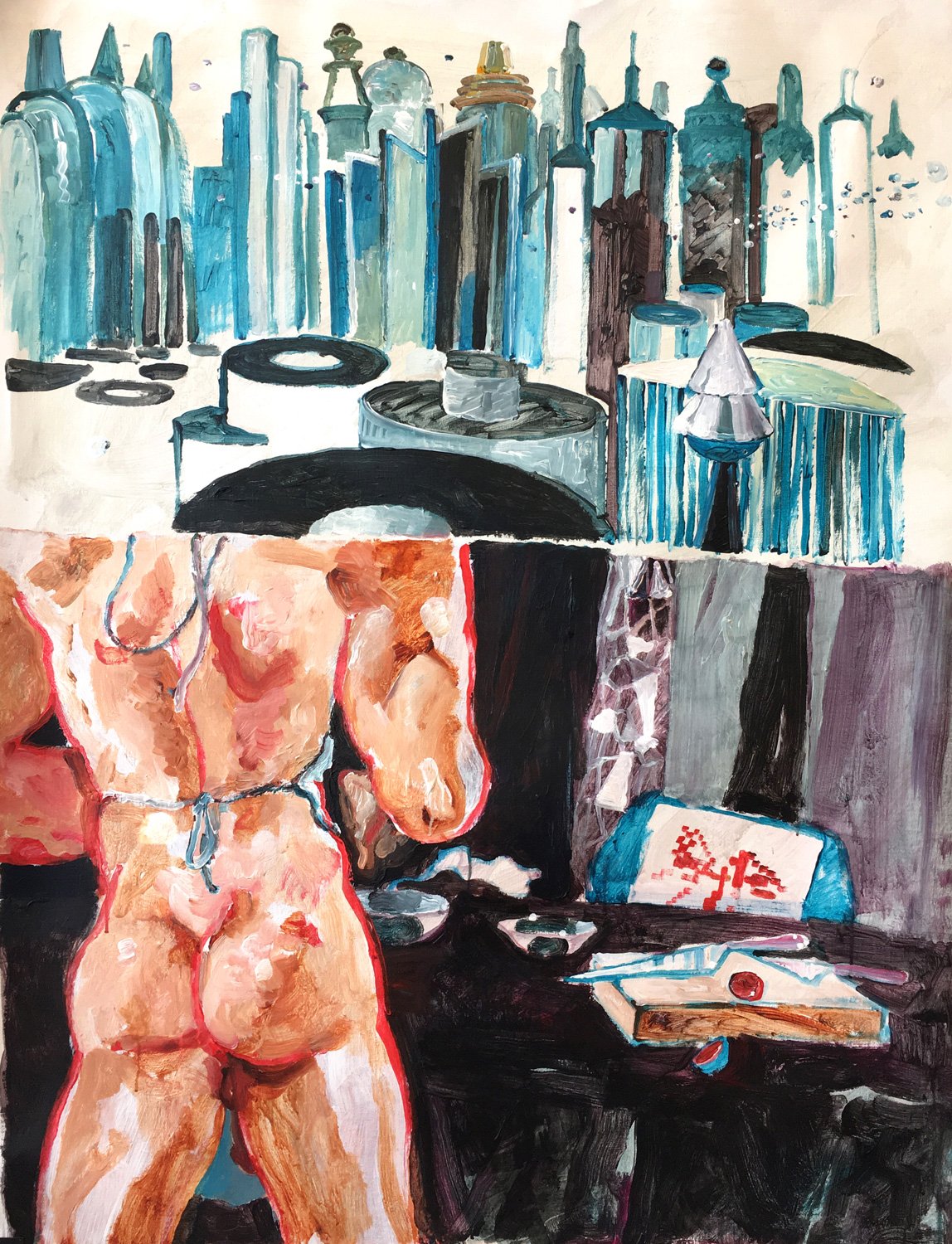

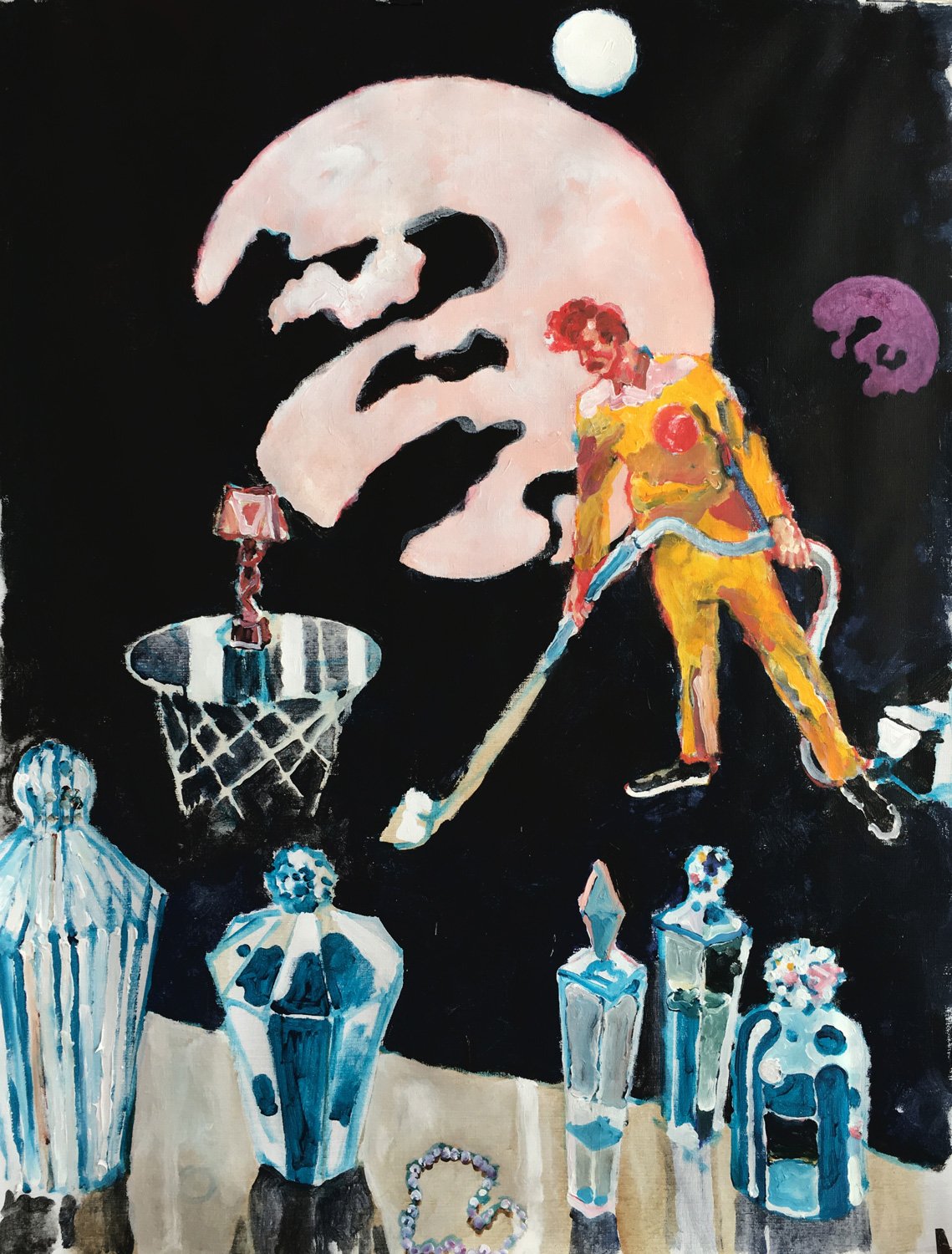

Dennis has a way of putting extraordinary attention into the details that most illustrators overlook, resulting in images that are irresistibly vivid and inviting. Like shots in a movie, removing all that is unnecessary, every image tells us the story by focusing on the little things that help it unfold. A hand that’s about to drop a glass, a vintage car hastily parked in a driveway, a woman purposefully putting on lipstick, a waiter hurrying in the background, wrapping paper crumpled on the floor, or, as it were, a curled-up post-coital male reproductive organ. The same goes for the sets where the action plays out. Just by drawing a table, a ceiling lamp, and a huge potted plant, Dennis, with seeming effortlessness, can create a complete restaurant interior in our minds. He’s obsessively interested in design and fashion history, and his work is effectively ‘styled’ through the use of design objects—whether existing or adapted from reality, as carefully selected as they are drawn—in order to set the mood, or place, or era, with the razor-sharp accuracy of a master set designer.

I met Dennis at art school, have published two of his books, and have never ever grown tired of seeing his work, as I’m sure you won’t either. For the benefit of Apartamento’s readers, I swung by Dennis’s studio to talk about Mad magazine, older brothers, 007, and falling into, out of, and then into graffiti again.

close

close