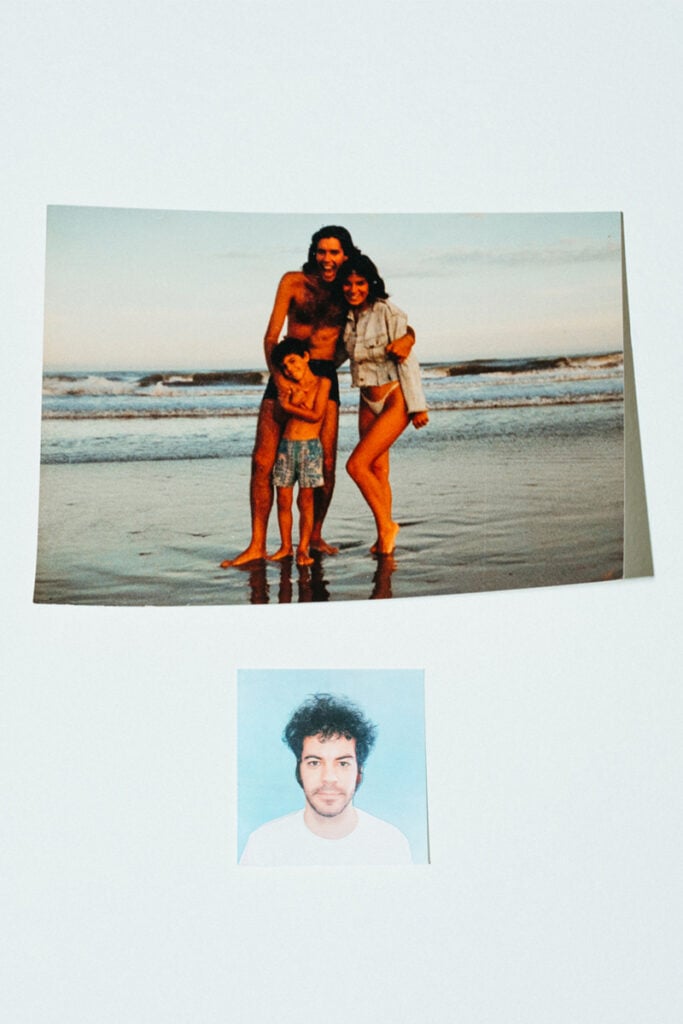

New York City: My favourite interviews are the ones that make you want to quit your job and follow your dreams, and that’s just what the conversation I had recently with self-taught Argentinian animator Dante Zaballa made me want to do. In Dante’s case, the impetus for radical change didn’t come from an interview though, it was a talk by Eike König, founder of the German design studio Hort. The message was that you need to dedicate yourself to the thing you love, and the rest will follow. However clichéed, it hit home. In the same week Dante moved back home, dropped out of uni, and quit his job, all to dedicate himself to his true passion: animation.

From there his drastic decision led to an equally drastic sea change, one from his native Argentina to the unknown streets of the German capital, and along with that sea change came access to new communities of similarly minded artists and animators. But still, after several years living the Berlin lifestyle, the desire for great change returned, and Dante packed his bags for the USA.

When I first got in touch last year with a proposal to collaborate on a new project with Apartamento and Clarks, Dante was living in Chicago but was already in the process of getting ready for yet another move, this time to New York City. The collaboration was baptised Desert Islands, the premise being that we would invite five different artists to each create artworks that would represent their very own desert islands, places they would go to in their dreams, given the prospect of actual travel was completely out of the question. Dante’s task was to breathe an extra layer of life into each short film using his signature style of animation. All the Zoom calls made me want to know more about Dante, so when the Desert Islands project was all done and dusted I suggested we jump on yet another Zoom call for a chat.

close

close