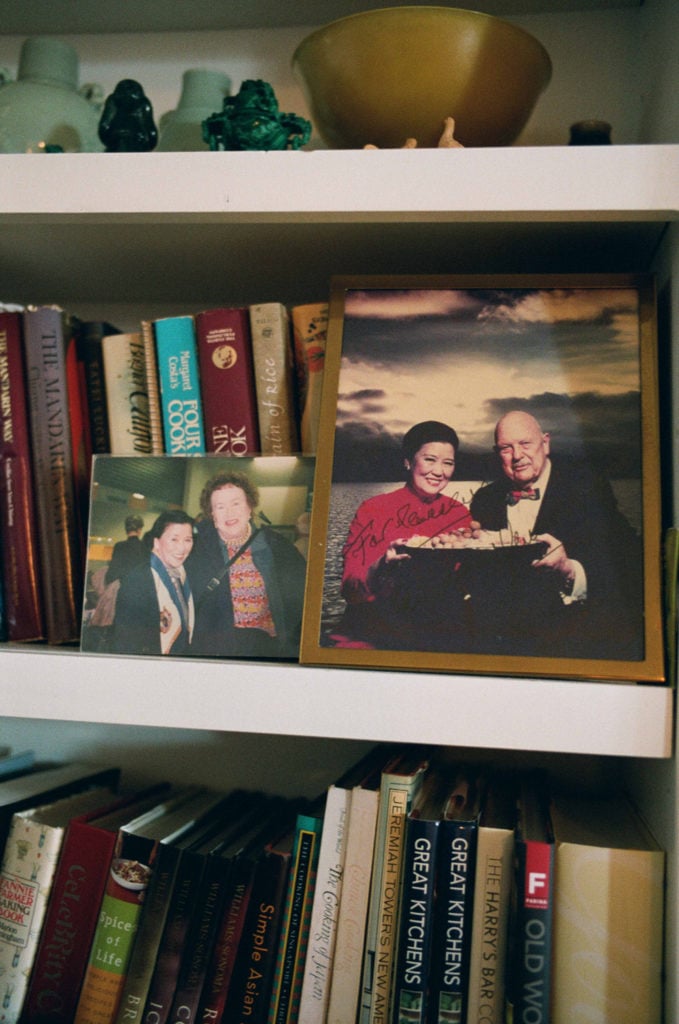

Alice Waters and Cecilia Chiang.

Text by Alice Waters

Photography by Max Farago

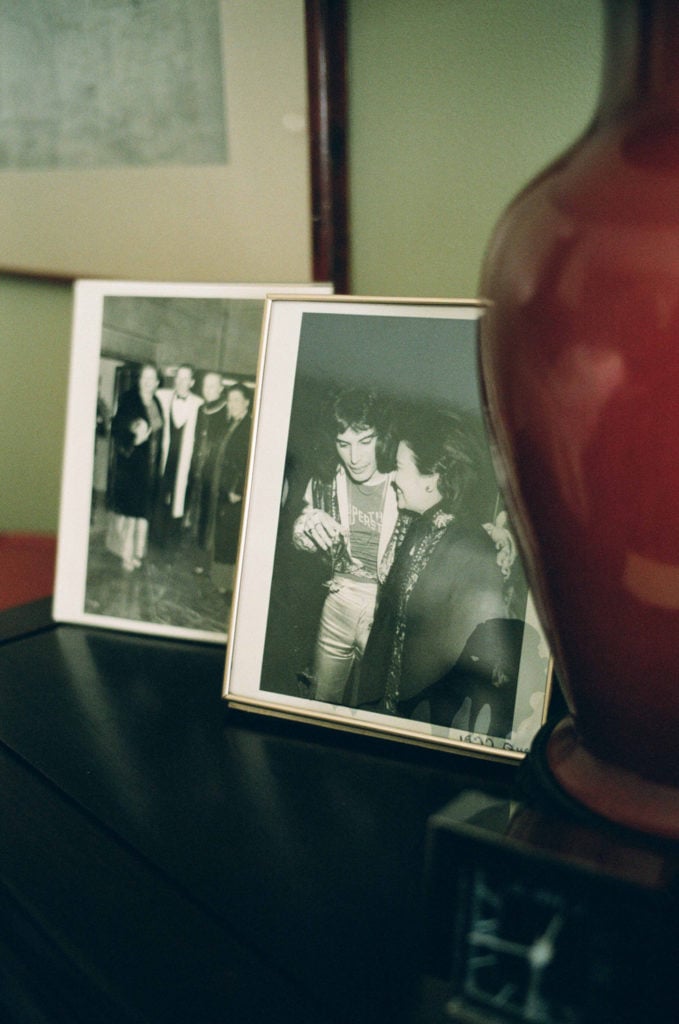

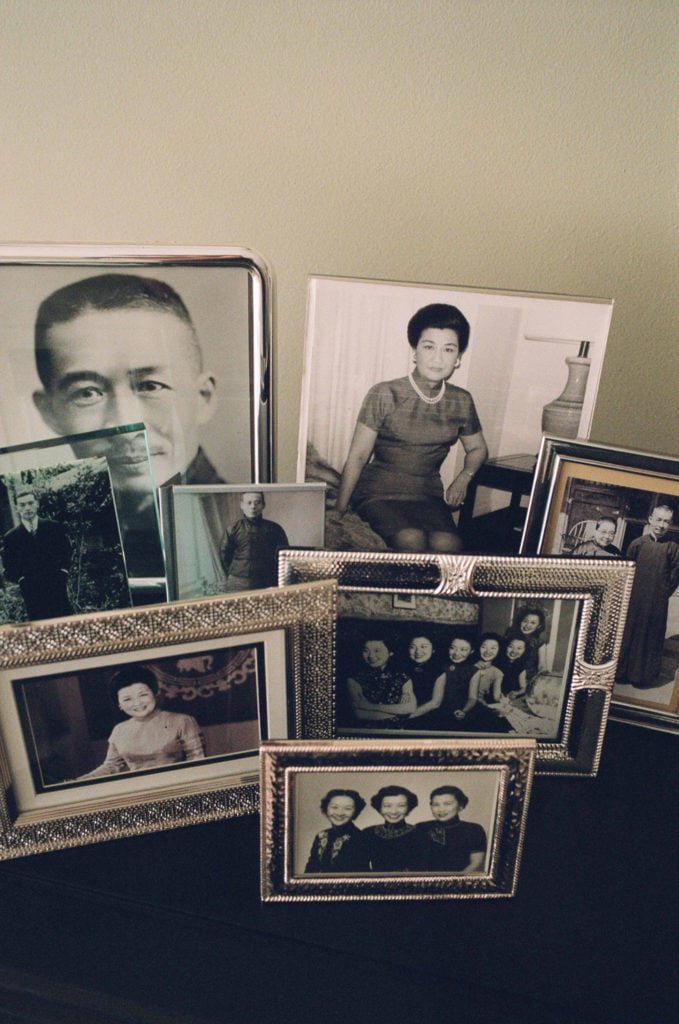

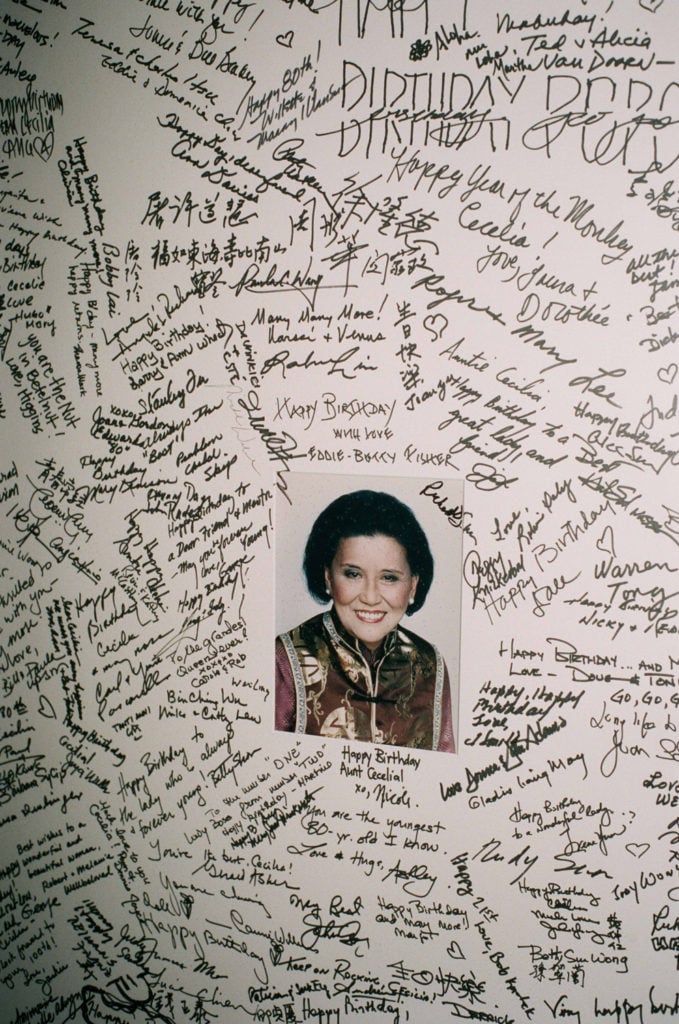

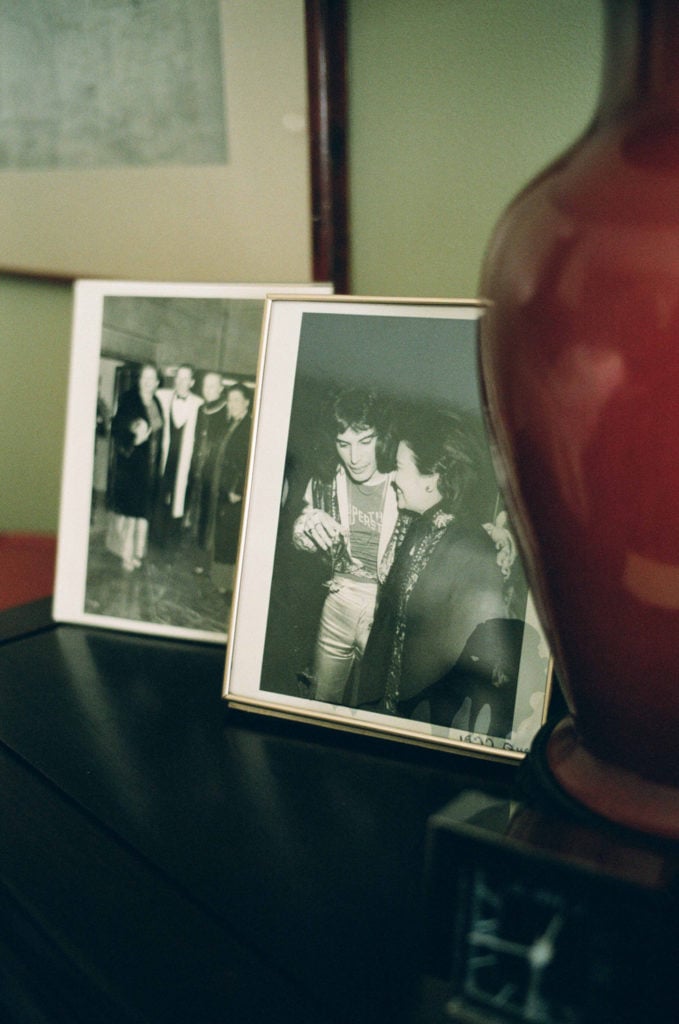

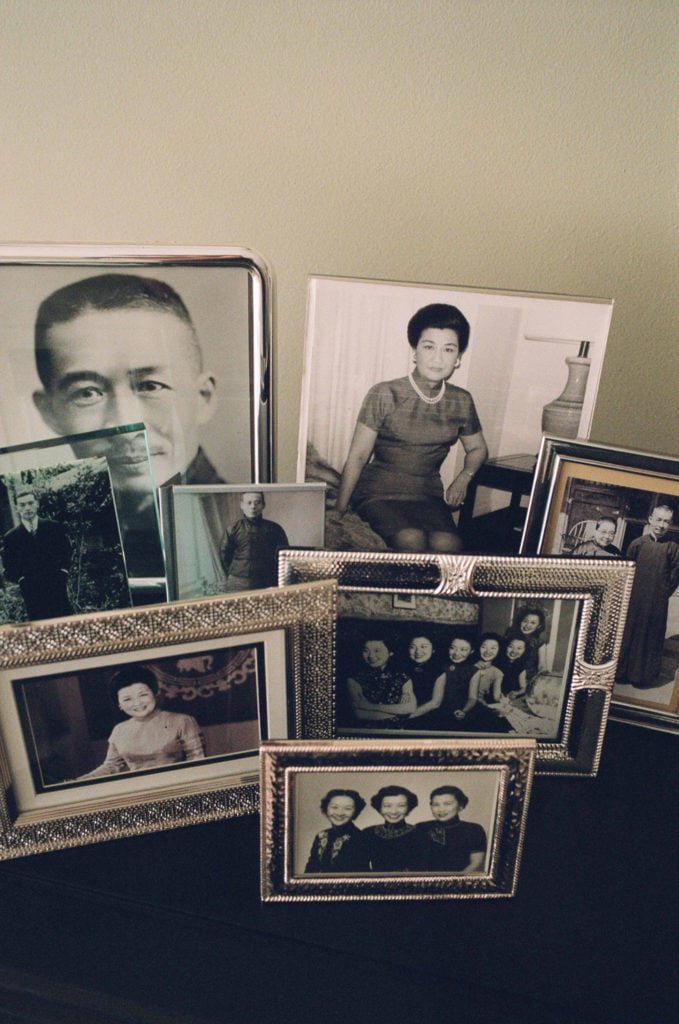

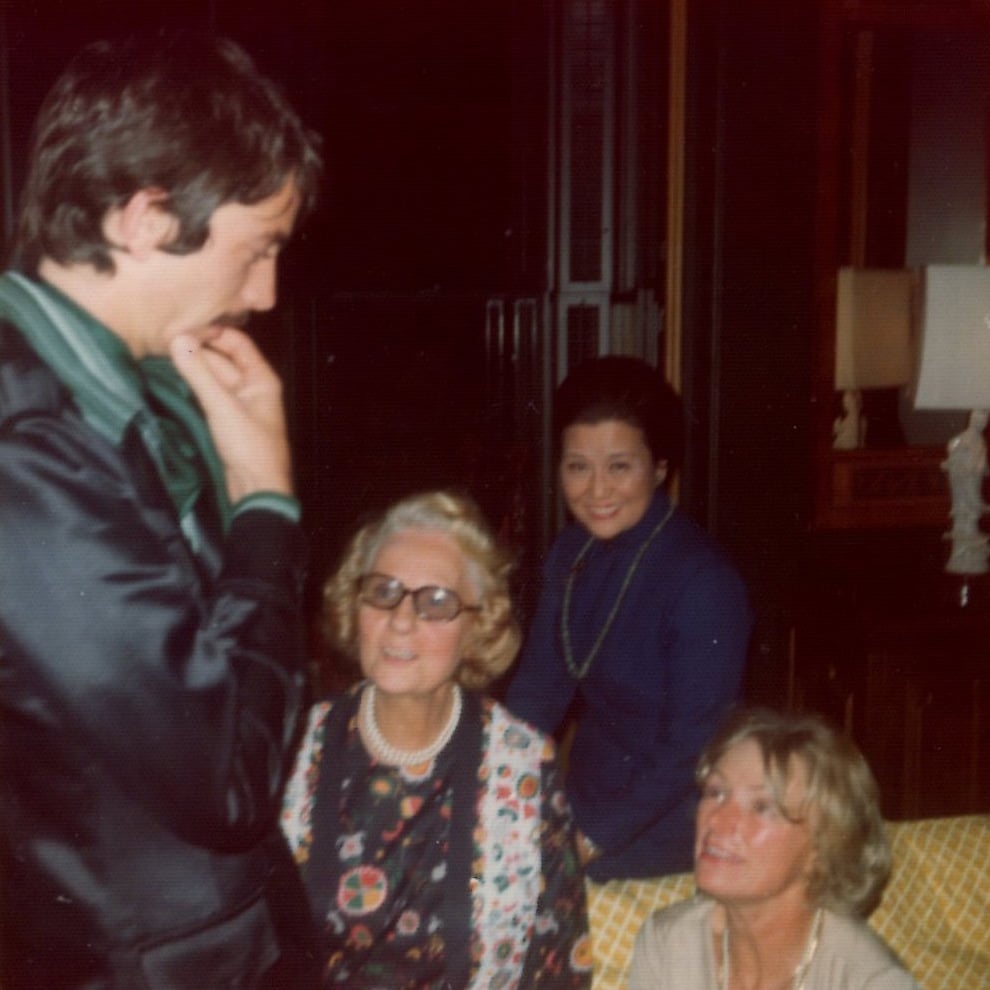

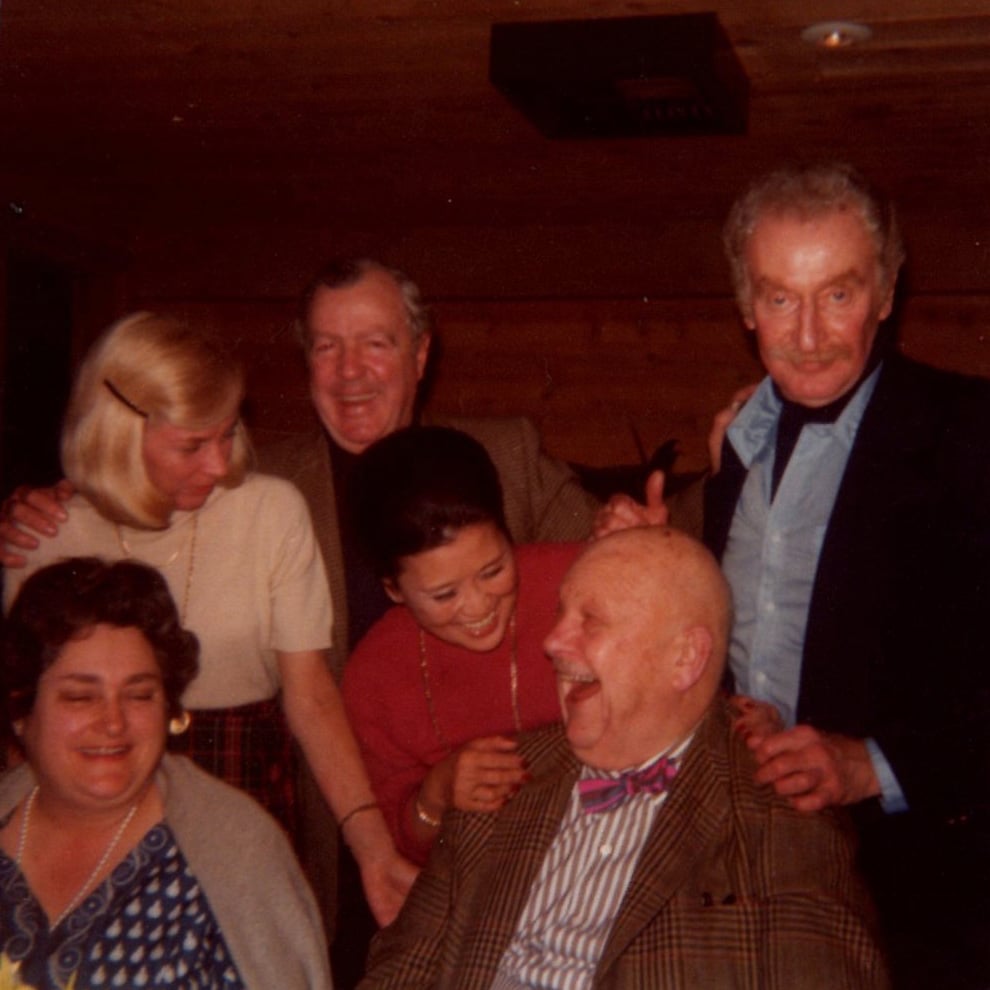

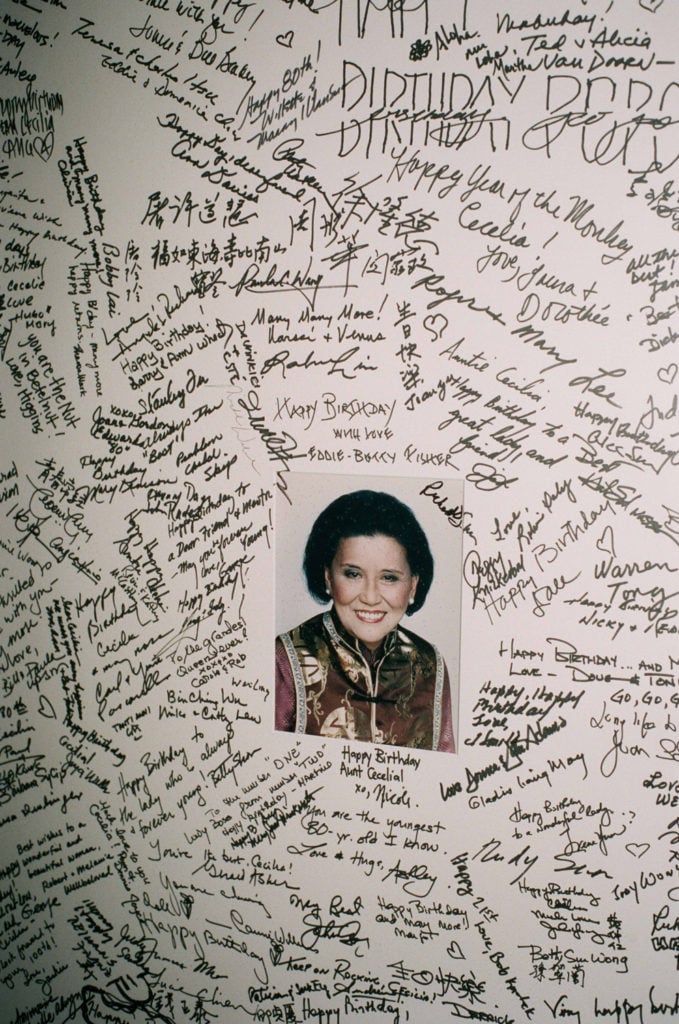

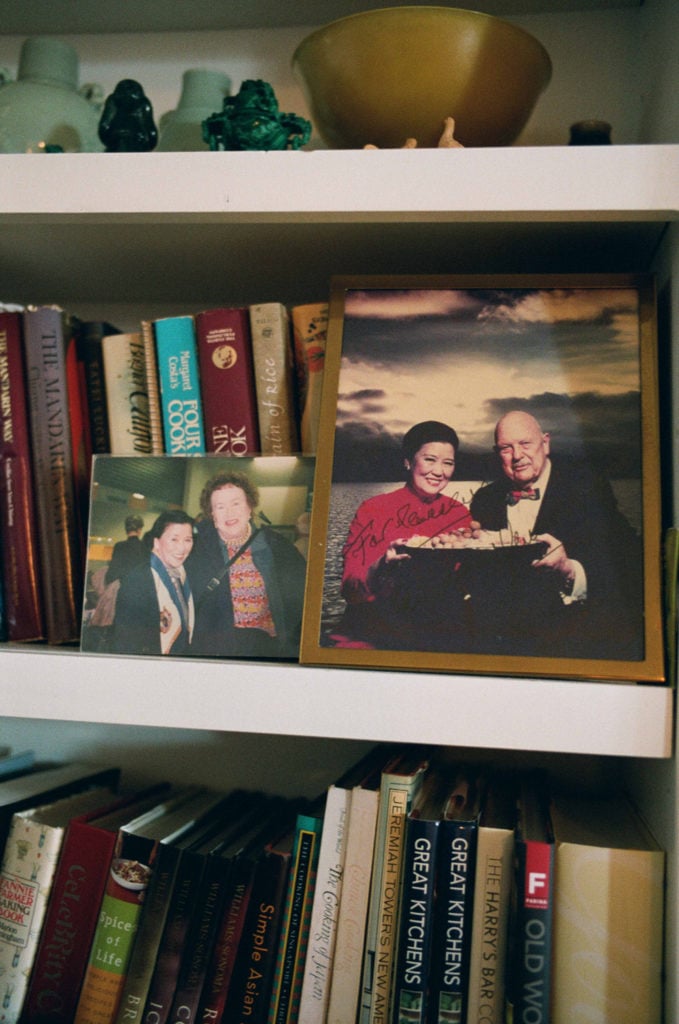

Archival images courtesy of Cecilia Chiang

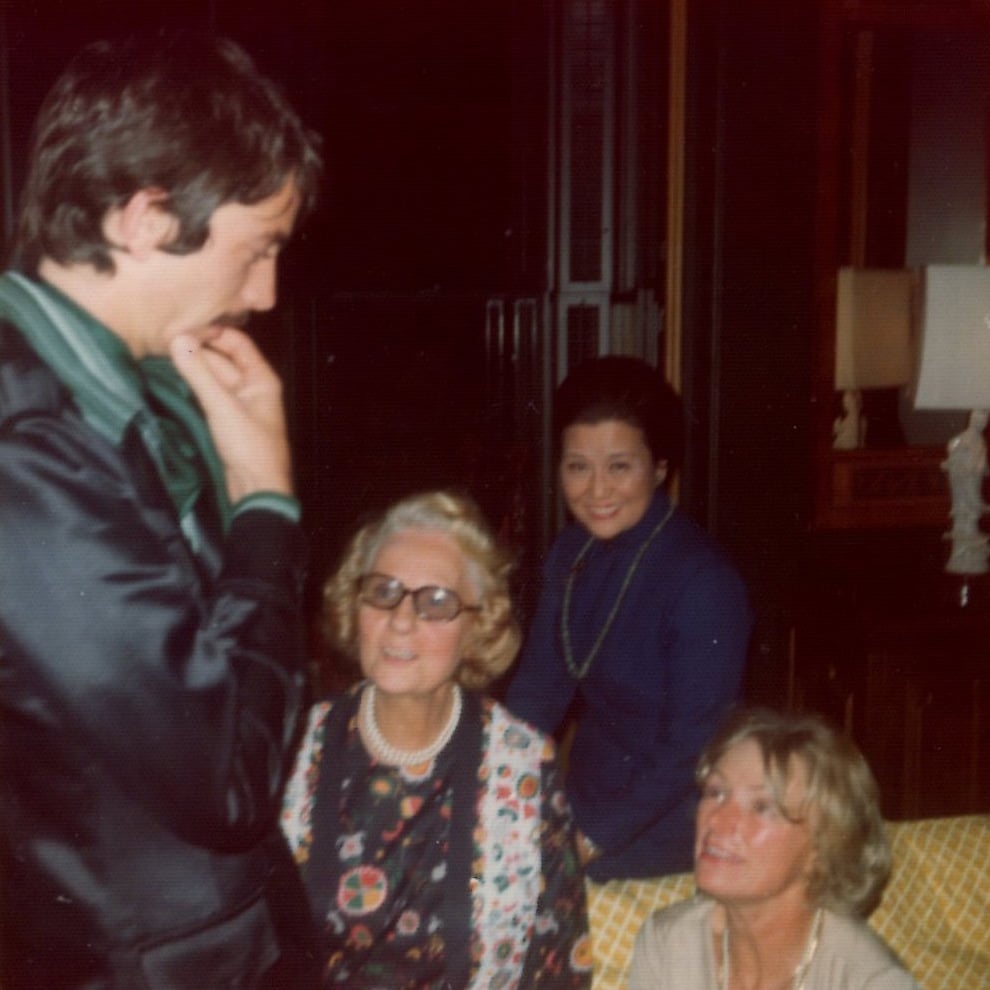

As part of Fanny Singer’s interview with the renowned 100-year-old restaurateur Cecilia Chiang (featured in issue #24 of Apartamento), we called upon Alice Waters, chef and founder of the acclaimed Berkeley restaurant Chez Panisse—and also Fanny’s mother—to write a short text about their 50-year-long friendship. The two originally met through the food writer Marion Cunningham, a long-time student of the cooking classes that Cecilia ran through her groundbreaking San Francisco restaurant, the Mandarin. In her text, Alice tells us about the trip the three of them took together in 1983, while Alice was pregnant with Fanny, travelling to China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan—shortly after the former had opened up to the rest of the world in the late ’70s, and for the first time since Cecilia had fled the country some 30 years earlier.

When I arrived with Cecilia in Beijing, we landed in what felt like the dead of night. We were the only airplane landing at that time and there were no lights on the runway, just one man on the tarmac to guide us in. And our baggage was the only baggage at the baggage claim. Still, Cecilia made up for it—she had at least a dozen gigantic suitcases. Marion Cunningham and I couldn’t imagine what she was carrying. It wasn’t until we got to the guesthouse—the same one that Nixon stayed in when he visited China—that we found out that her suitcases contained piles of gifts for her family: typewriters, gadgets, books, and other things they’d requested from America. And, we later learned, she planned to take back tons of ingredients to the States in the empty bags.

China had only recently reopened, so it felt truly desolate in Beijing. There were no tourists, just a scattering of people in all the public spaces. In Beijing, I was shocked by how empty even the markets seemed, and there were so few restaurants. Cecilia was worried we wouldn’t find anywhere good to eat. We walked around the Forbidden City virtually alone. We even had lunch at the Summer Palace—with the place to ourselves, this grand pavilion. But wherever we went, people followed Cecilia because she spoke Mandarin; it distinguished her, made her seem important.

The night we arrived she wanted us to have Peking duck in a little restaurant she remembered, so we stopped in on our way to the hotel. The duck, sadly, wasn’t as good as she recalled; it was oily and not at all crispy. But when Cecilia saw someone at a neighbouring table wipe their hands on the curtains, that’s when she’d had enough. She stood up abruptly and said, ‘We are leaving immediately!’

From Beijing we went to Shanghai, where we stayed in a fancy hotel, a kind of high-rise. In the morning, Cecilia rushed in to tell us to look down from our bedroom windows. Everywhere you looked, in every open square or park, people were doing their morning exercises in unison. I’d never seen anyone practise tai chi before—it was amazing, even mesmerising.

Cecilia wanted to take us to this one restaurant she remembered in Shanghai. When we arrived, however, it turned out a wedding party had taken it over for the day. But Cecilia was undeterred. After some tense negotiations, and consultations between her, the owners of the restaurant, and the bridal party, the married couple agreed to invite us in to take part in their celebratory feast. Cecilia was so pleased; it was as if she were inviting us to the Mandarin. I’ll never forget that meal. I had never had sweet and sour fish like I did that day. Or freshwater chestnuts. It was the best food we had in mainland China. Taiwan, however, was unlike Beijing or Shanghai: there were restaurants and hotels everywhere, and we dined with Cecilia’s friends nearly every night. We went to one little restaurant that I particularly loved, which Cecilia said she favoured because it combined the best of Japanese and Chinese culinary influences—an island cuisine that pulled as much from one neighbour as the other. I remember we had these divine razor clams, with ginger sliced in beautiful diagonal slivers to resemble the shape of the clam.

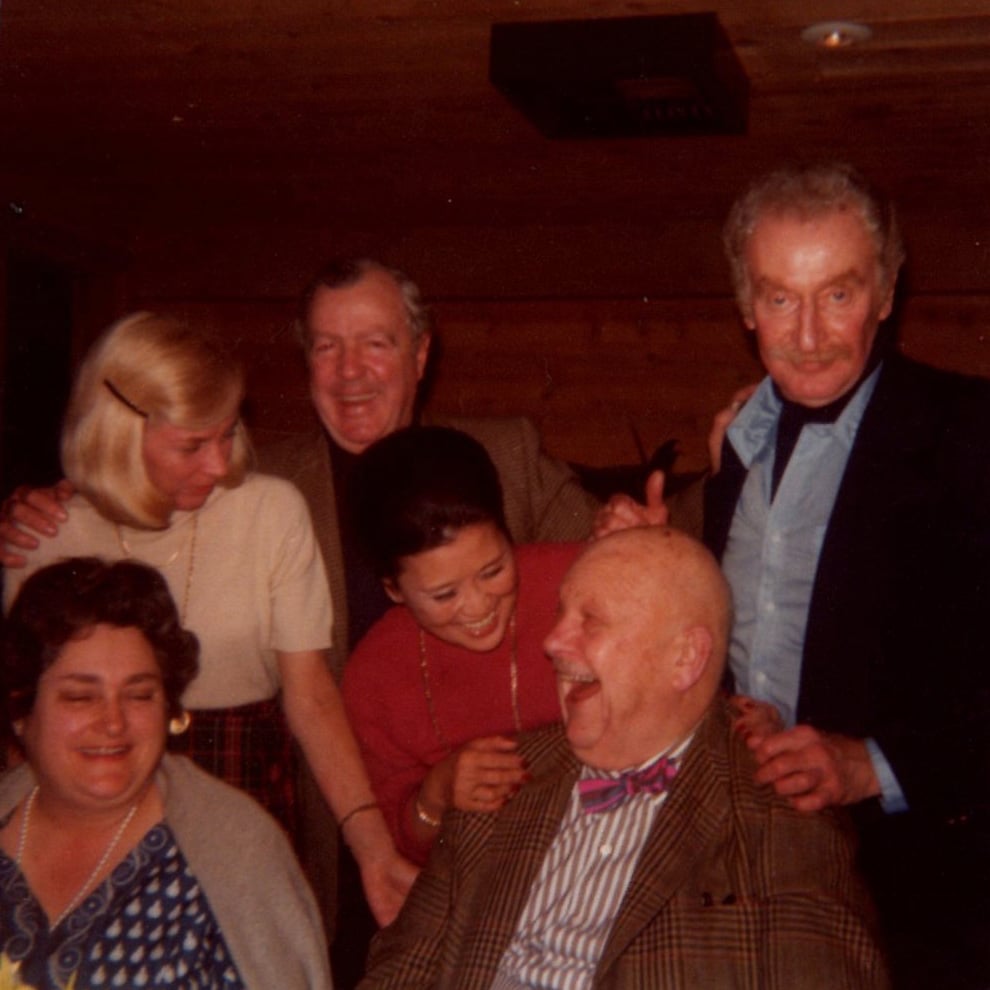

Having a banquet at the Mandarin with Cecilia was always such a special experience. There were at least eight or ten people at these meals, but I was given the best seat, right next to Cecilia, and very often also next to James Beard. She would constantly be serving me, using the other end of her chopsticks to distribute little perfect morsels, before flipping them around to eat herself—I always found her adherence to etiquette remarkable. And James Beard would pontificate, espousing information about absolutely everything: he knew every ingredient, every dish on the table. He had truly encyclopaedic knowledge of food. Cecilia would orchestrate the courses perfectly to follow one another, always creating a harmonious whole. These meals were very, very seasonal, so, for instance, you would only ever have bamboo shoots in the spring at just the right moment. It meant that you also never knew what to expect—it was always changing. Texturally her food was especially fascinating to me: there were fried dishes, steamed dishes, slow-cooked dishes. Other things that arrived wrapped and required unwrapping like gifts. We always began with cold platters of hors d’oeuvres and so many vegetables; she was a master of vegetable dishes. And then at the end a whole beautiful fish strewn with ginger. We all loved her Peking duck so much that it was the one thing that became a sort of fixture. But really, there was nobody else presenting dishes in that manner. Especially when it came to Chinese food at that time. I have the clearest memory of this one soup that came in a beautiful flowered bowl and it was completely covered in fresh coriander, a sea of fragrant green. Right at the moment it was set down at the table, there was an earthquake. The soup splashed as if in slow motion from one side of the bowl to the other.

I think Cecilia most influenced me in the way she thought about a menu, because it’s how I think about menus now too. I always consider colour, texture, sequence—the first taste has to really grab you, the last taste must let you go, leaving you with a clear remembrance of the meal.

close

close