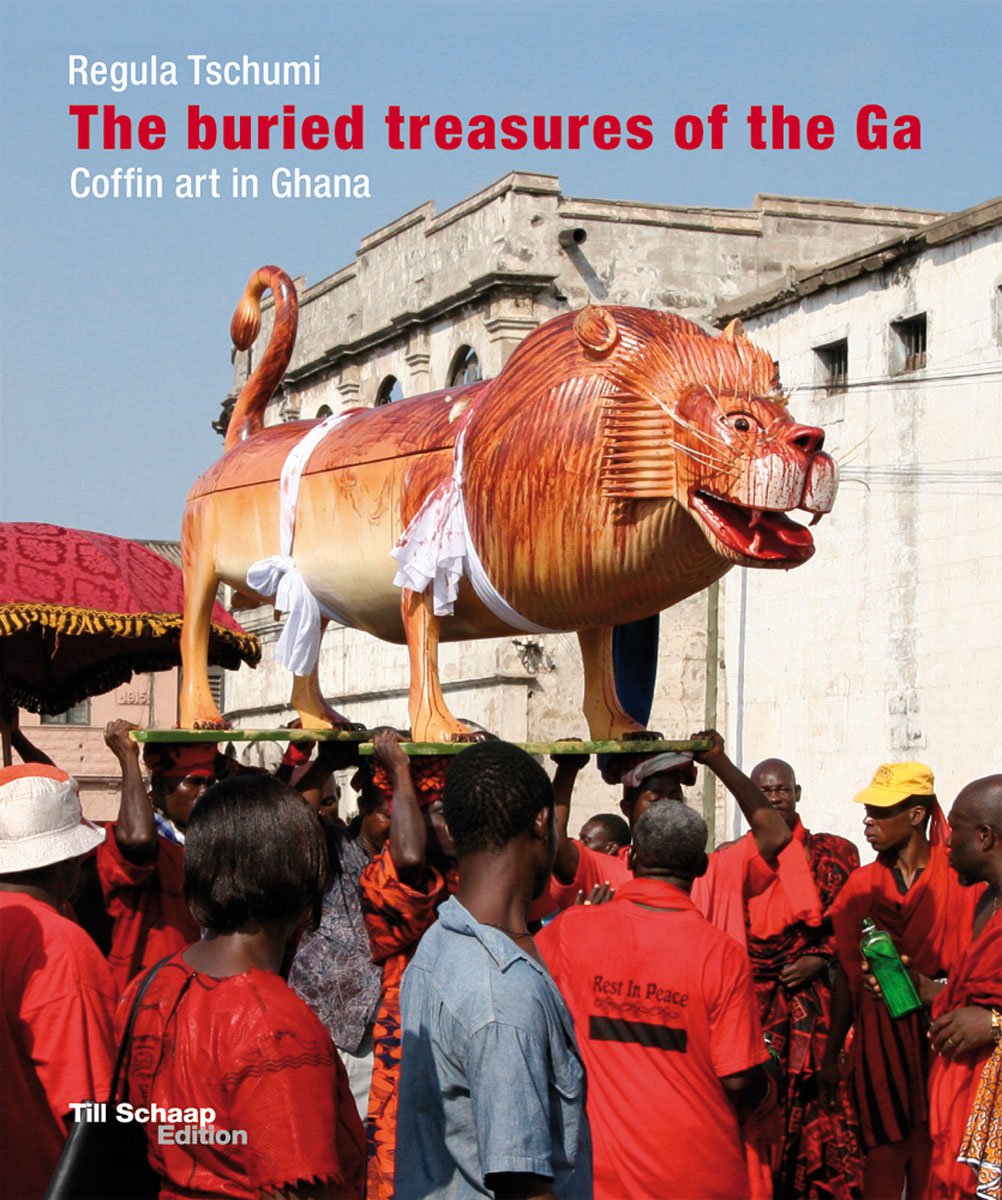

The Ghanaian coffin artist Paa Joe is featured in issue #28 of Apartamento magazine, with archive photos by the Swiss anthropologist Regula Tschumi. Click here to get your copy!

An introduction to figurative coffins

In 1999 I spent a week in Accra, the capital of Ghana, to see an exhibition of contemporary African art from West and South Africa. While there, I also visited the workshops of several coffin artists and came across their figurative coffins for the first time. Creating these coffins is a highly specialised profession for which apprentices are trained for many years and, if successful, will have customers travelling far and wide to commission a coffin made in their favourite workshop. I was fascinated.

Back home in Switzerland, I started to look for catalogues or articles that might tell me more about these artefacts. Much had been written about them, but it soon became apparent that most authors had drawn on the same source: an illustrated volume by the photojournalist Thierry Secretan, Il fait sombre, va-t’en: Cercueils au Ghana, from 1994, where the coffins were generally viewed in the same terms as Western art. The carpenter Kane Kwei from Teshie was believed to have invented the figurative coffins of the Ga—the people of the south-east coast of Ghana—around 1950. There were no scholarly works or empirical studies that seriously examined their origin, function, and social context from an emic perspective, and that aroused my curiosity.

Between 2002 and 2013 I travelled to Accra 19 times and spent a total of 41 months there. From 2002 until 2006 I was only there for a few months while I researched figurative coffins, but from 2007 to 2013 I spent between two and four months in the Greater Accra Region every year as I worked on my dissertation at the University of Basle. My first book, The Buried Treasures of the Ga, dealt mainly with the work of Paa Joe and questions of how the figurative coffins are made and used, while the second, Concealed Art, is my PhD thesis and explores why the Ga began to use figurative coffins and what role the mysterious palanquin played in all this

close

close