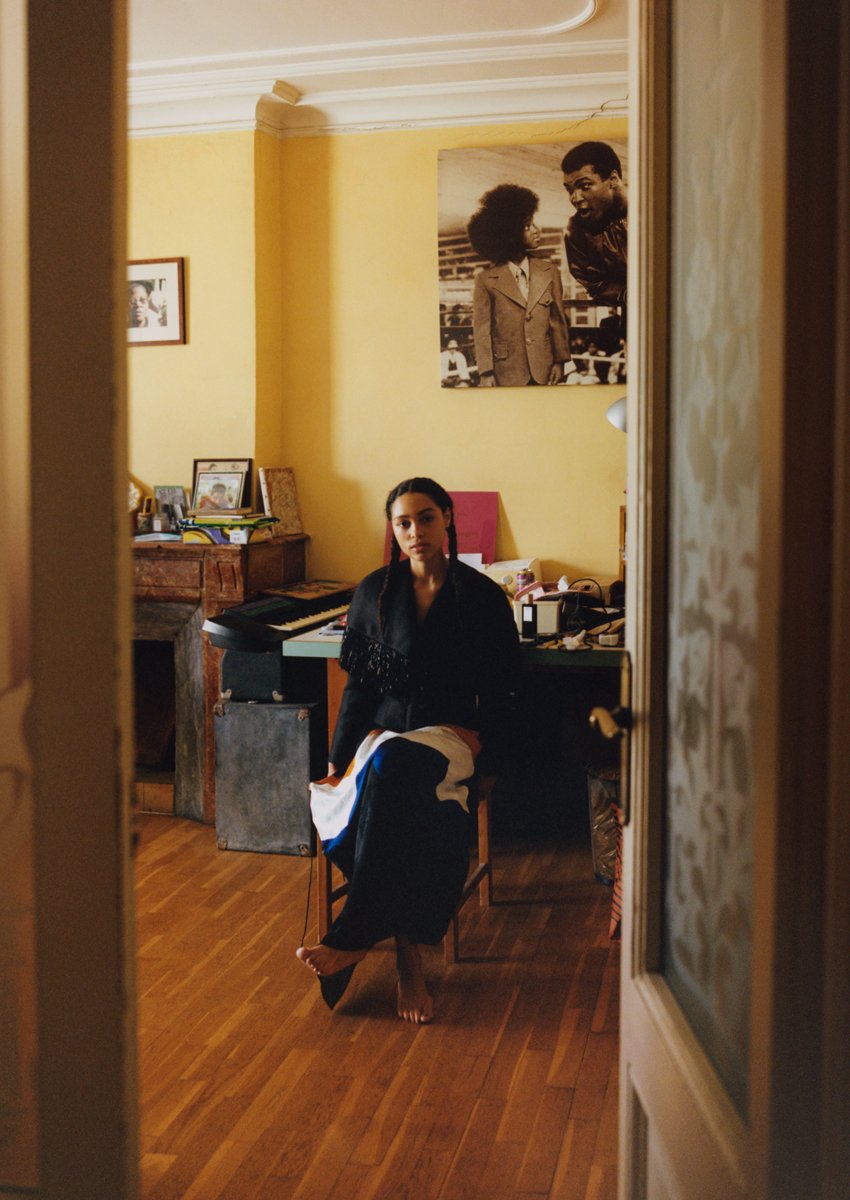

‘You know my music likes to be listened by you’, says the Instagram bio of Neï Lydia Kibol Bikôkô Pineda—a nod to the book Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke, which her mother gave her before she travelled to New York. It was there that Neï, finally free of her student routine, began her music project. One evening at sunset, while reading over her lyrics in Sunset Park in Brooklyn, Bikôkô—which also means ‘sunset’ in the Basaa language of Cameroon—envisioned an album on which each song would represent a moment of the day. Have you picked up on the synchronicities? If so, repeat after me: Aura Aura. The title of Bikôkô’s debut album is an African call and response that demands your attention. Have you been paying attention? If so, repeat Aura Aura, and we’ll materialise in an apartment on Carrer Princesa in the epicentre of Barcelona, to talk with Bikôkô.

Neï lives in an open and luminous space, where sounds circulate restlessly from end to end. Any place is conducive to sitting down and talking, so almost without thinking about it we choose the kitchen while her father makes us coffee and then disappears. I’d be lying if I said that we started the conversation there, because we began sharing ideas as soon as we greeted each other at the door. She’d already told me about her fondness for yoga and Ayurveda; her constitution, according to this practice, is Pitta-Vata, where fire and water dominate, but air and space also exert a strong influence. We have to start somewhere though, so come and sit down with us. Bikôkô senior will pour you some coffee and Neï, Bikôkô junior, will welcome you with a smile that’s more than contagious. And given her album is ordered by the phases of the day, we decided that we’d do exactly the same with the interview.

close

close