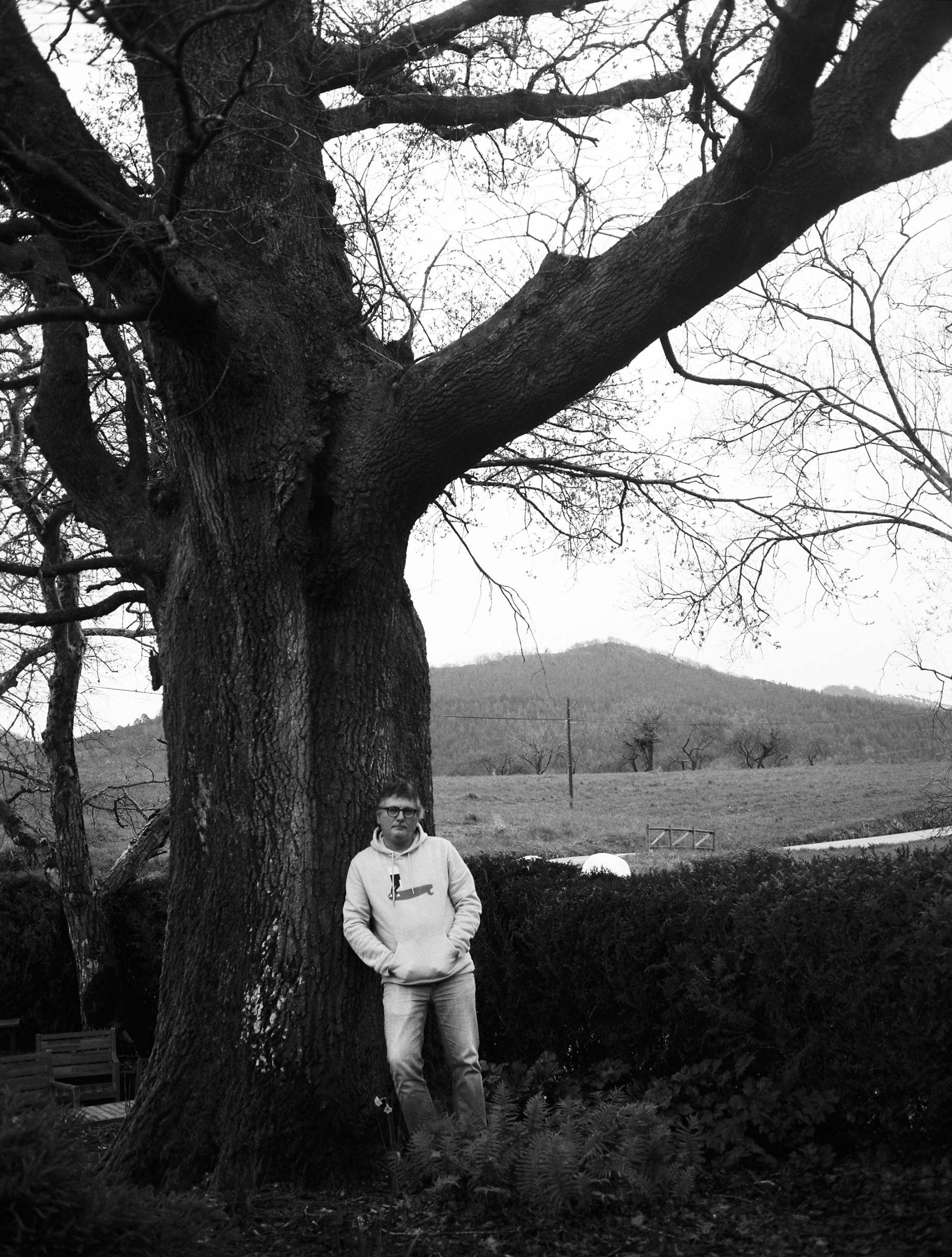

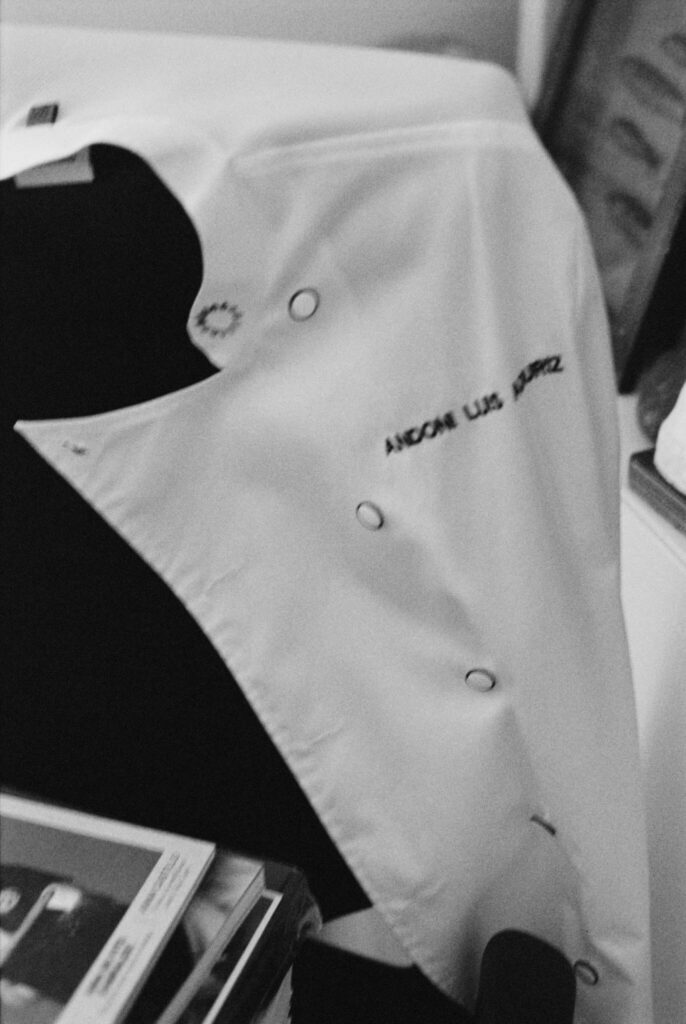

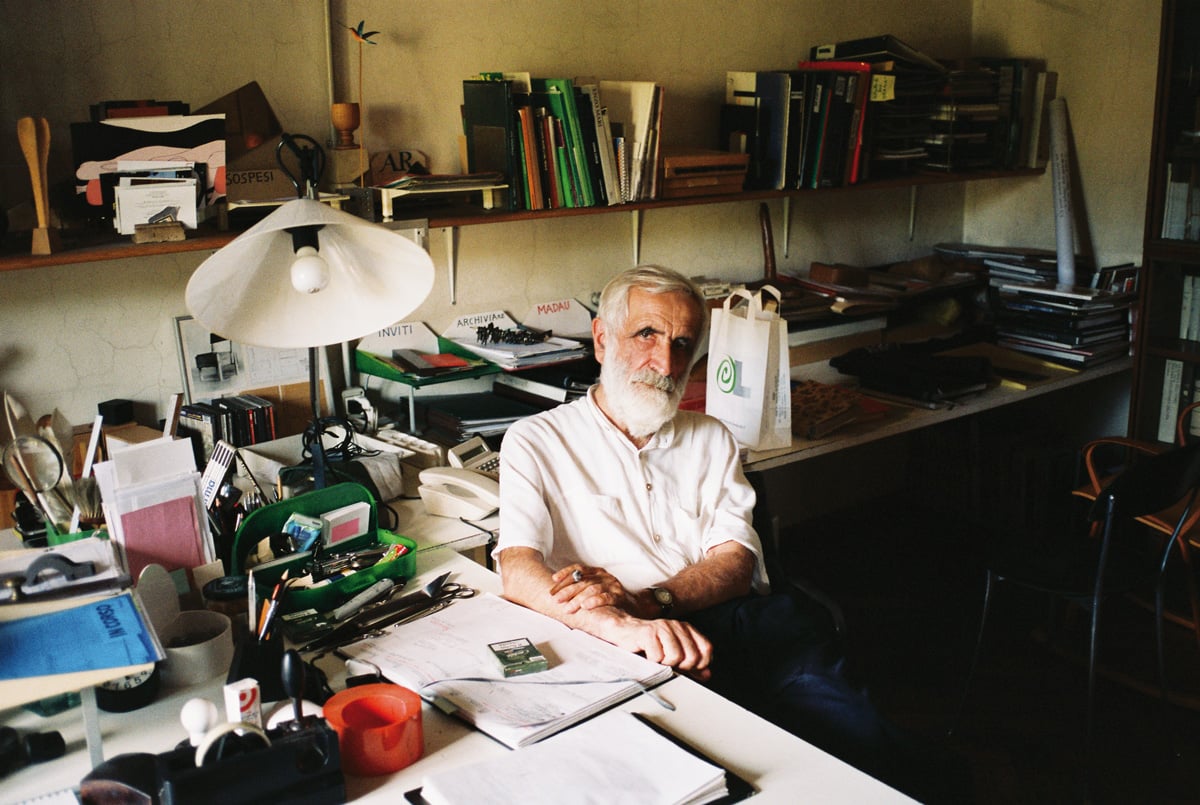

Rentería: Andoni Luis Aduriz is a self-described part of the avant-garde in cooking, which leads to the question of what that actually implies. How radical can a restaurant be, or a chef making one of three meals you’ll eat in a day, all soon to be physically expunged from the body? Ask Aduriz what his priority is though, and I doubt he’d say it’s to feed people. His restaurant, Mugaritz, has consistently held two Michelin stars since 2006 and is currently ranked #14 on the World’s Best 50 list, but he also objects to it being called a restaurant. Food is part of the equation here, sure, but it’s also not everything.

Aduriz graduated from cooking school in San Sebastián then worked for some of the most celebrated restaurants in Spain—Arzak, Akellare, Martín Berasategui, and El Bullí among them—absorbing the desire to subvert culinary conventions that’s shaped Ferran Adrià’s whole ethos. An ethos that Adrià summarised in an episode of Bourdain’s No Reservations by saying that if he already knows how to cook a tortilla, much better to try and cook something he doesn’t know how to do. Whoever created that first tortilla created a new technique and a new concept—and Aduriz, like Adrià, exist to do the same. Back at Mugaritz, Aduriz proclaimed that our most extraordinary skill as human beings is the ability to take something non-existent and make it real, the ethos that he, in turn, tries to embody in his kitchen.

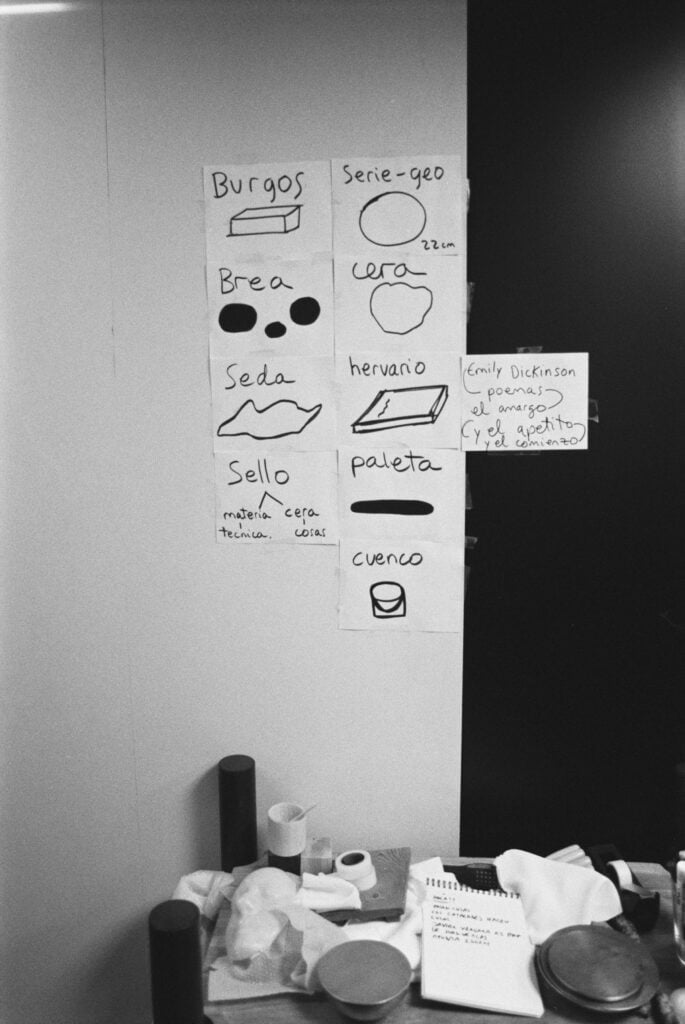

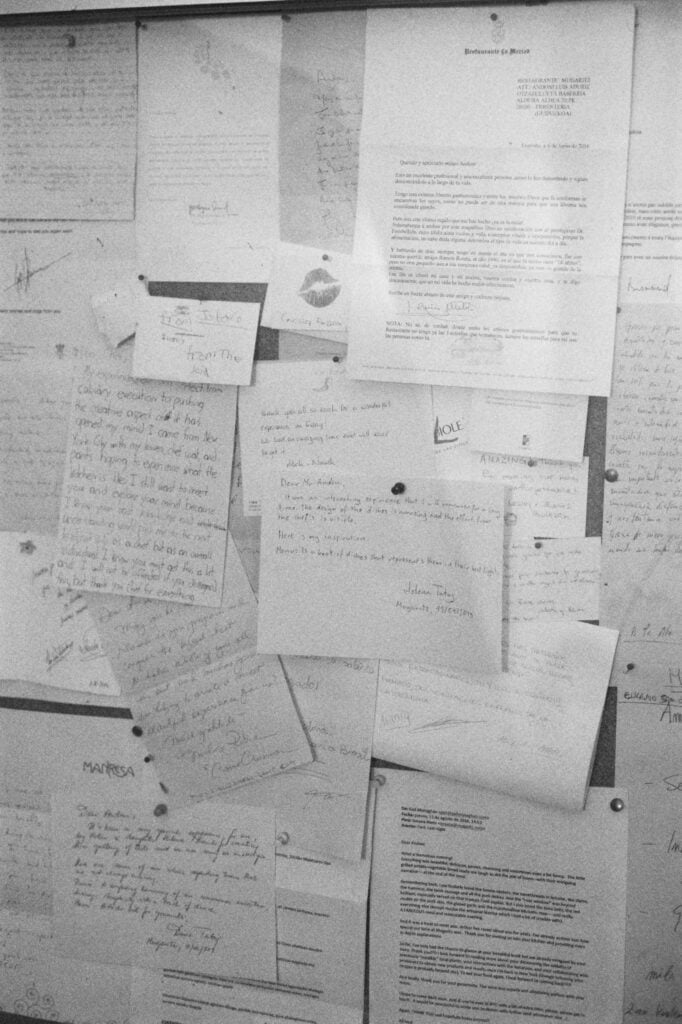

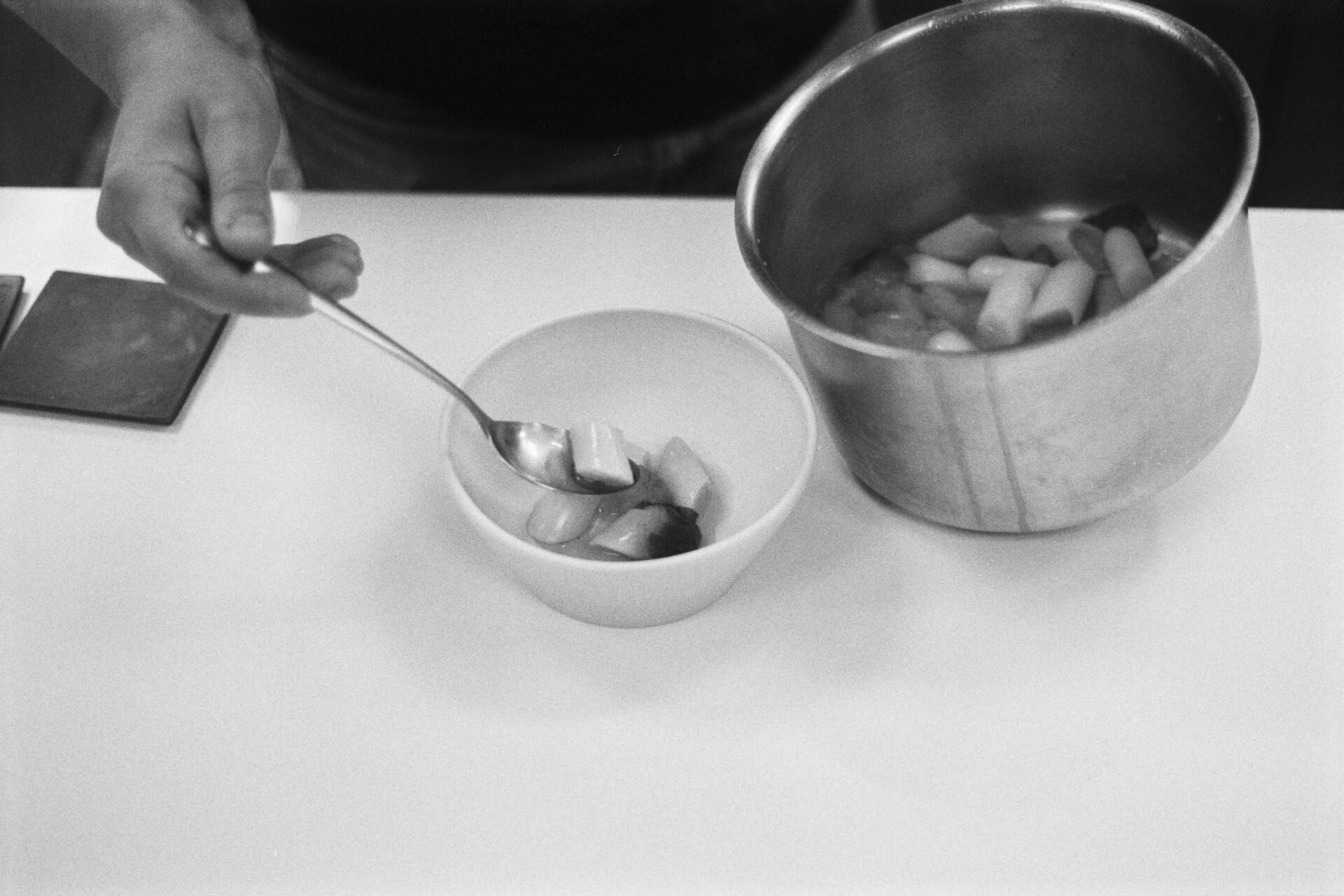

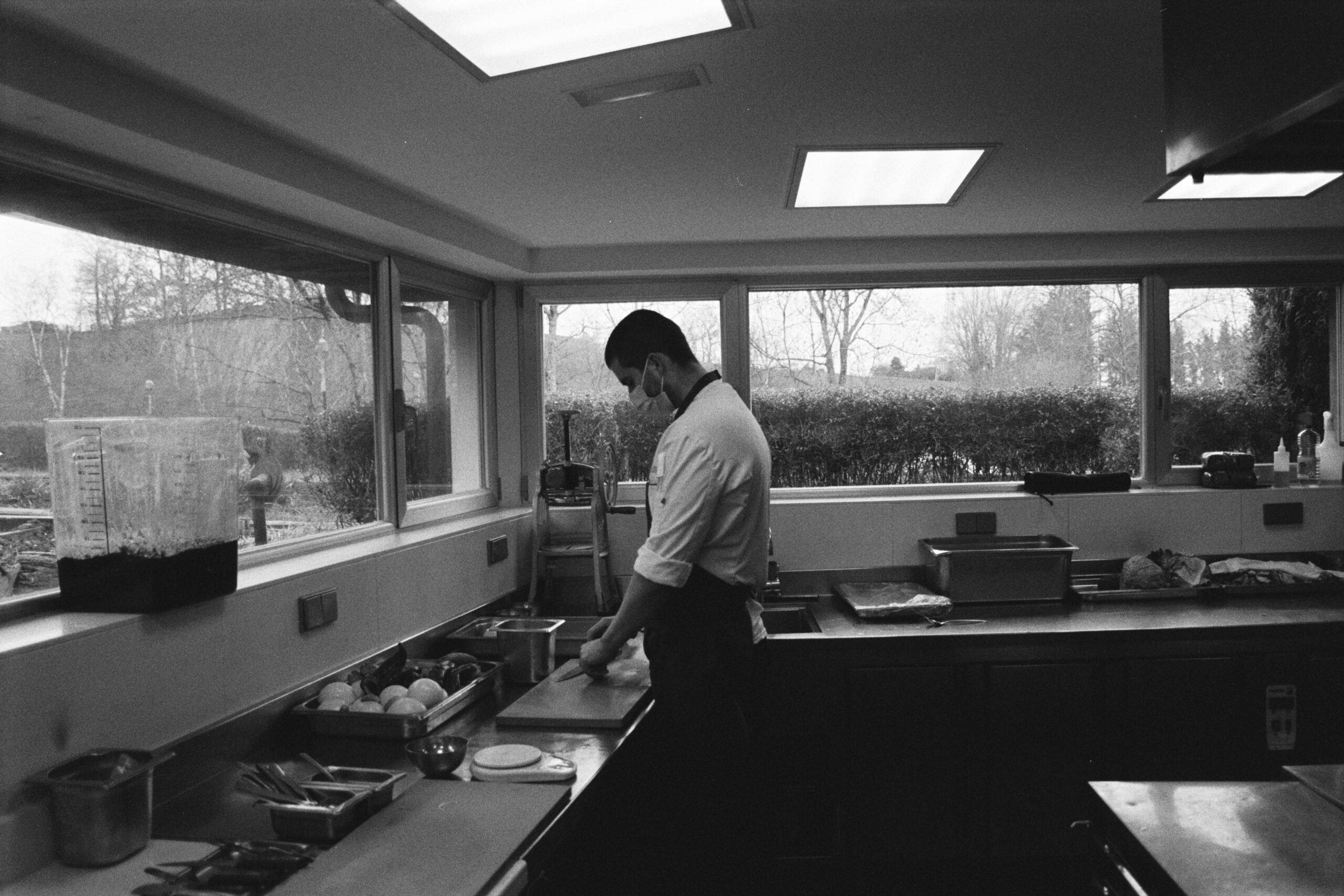

For a project we were working on with The Natural Wine Company, we visited Mugaritz during its annual four-month closure, a period for creativity when they test ideas and build their new menu. The kitchen had a wall covered in A4 sheets of paper with words and rudimentary drawings—mycelium (the vegetive part of a fungus), meat honey, silk, and finger—concepts that were eventually folded back into a 25-course tasting menu, this year based on the theme of ‘taste’ and asking diners to think more deeply about what’s good, what’s bad, what’s meant to entice or repulse, and what they really think about the dish in front of them when all the usual signifiers and prompts of fine dining are confounded or absent. If you think of daily life and the vast repetition of experiences, the controlled messaging around this good and bad taste, the sublimation of instinct to expectation, maybe a restaurant that supplicates you to reconsider all of this could, in fact, be somewhere out front in the avant-garde.

close

close