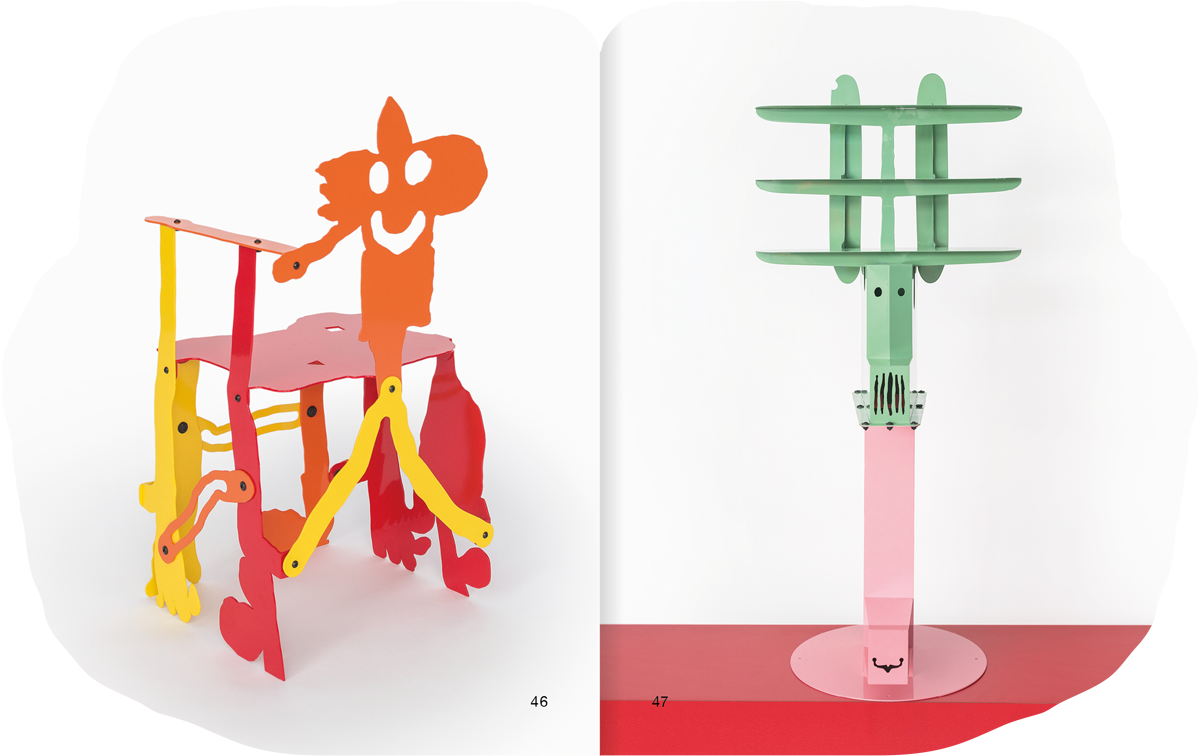

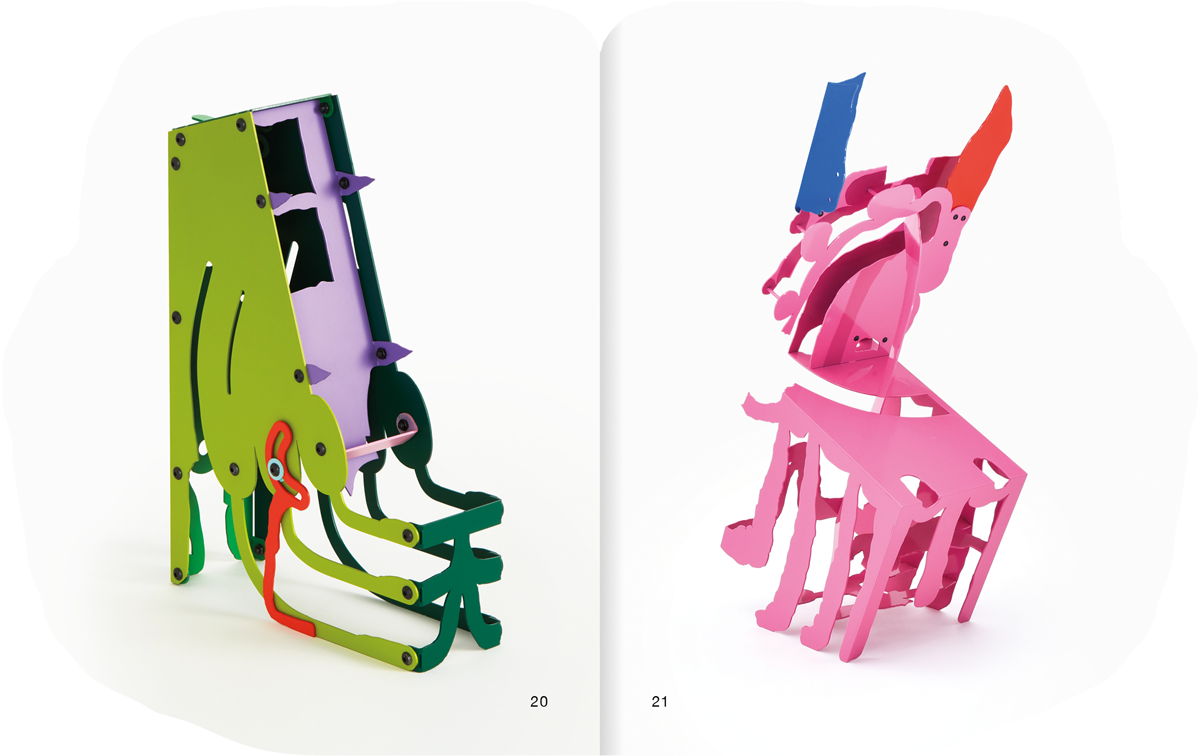

Andrew: Thinking again about this question of, ‘Why make a chair?’ Maybe part of the answer for you is, any piece of furniture is a small-scale impact on a space. Furniture is very practically part of the environment.

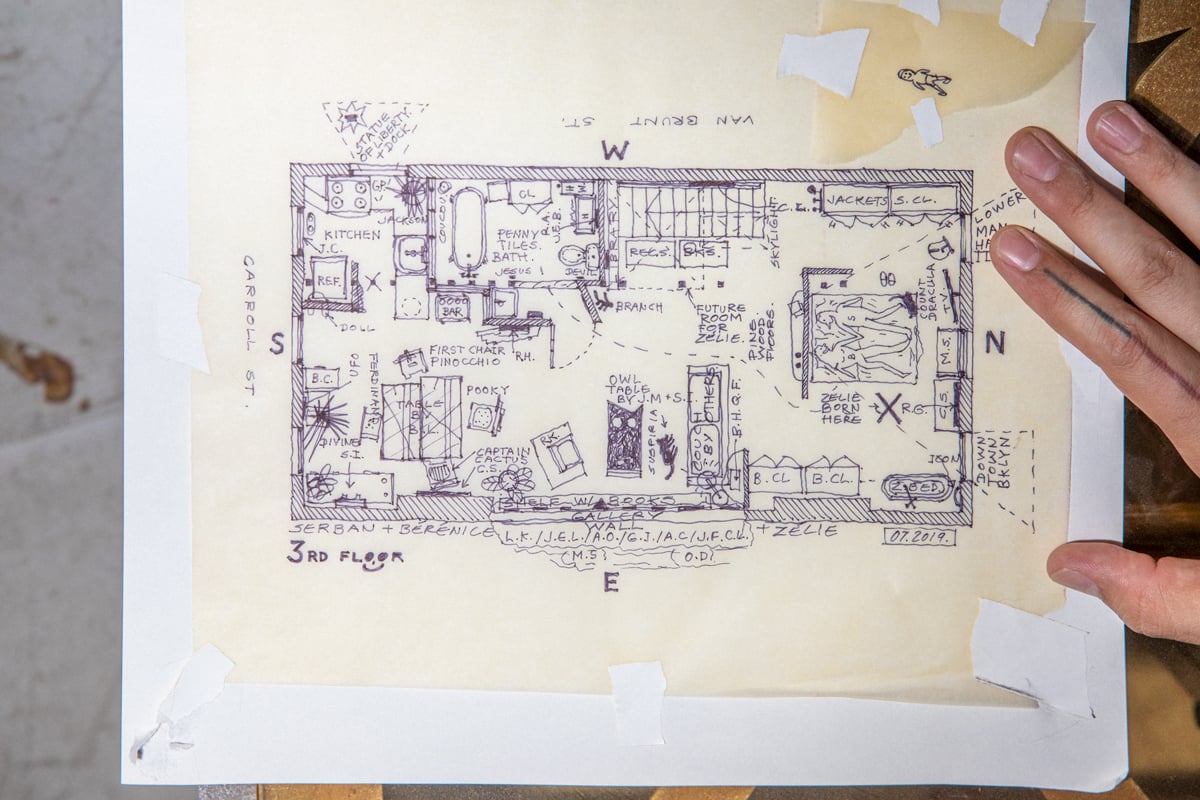

I had this thing when I was teaching: the cat in architecture. It’s the concept of an empty room versus a room with a cat in it. What is that cat? What is that disturbance to a space? Let’s say space is a positive rather than negative. Then the cat is a negative to that positive space. So what is that negative space that gets formed by a cat moving in a room? What is it about bringing something into a room that’s maybe not controllable, maybe not part of it? And what is the responsibility? How do you interact? That goes back to the idea of misuse as well. I’ve had pieces during a show where people put a coat on it and you’re like, ‘Whoa, this is an exhibition’. It’s the worst.

Kristen: Do you think there is anything negative about participating in design shows ultimately?

Andrew: This is the hardest thing. You could sell someone a painting and they could paint over it, but presumably they wouldn’t. Whereas you build someone a house, and they feel well within their rights to paint the house.

Kristen: Or if you’re participating in a design-specific show, I wonder about how that goes into your canon, and how that context may cement your work in some people’s minds. This is something Andrew and I talk about a lot, and I don’t know if there is really an answer.

Andrew: It’s the chair-guy problem.

Yeah, of course. But I would always surprise. I will maybe at times sabotage, because of that surprise. I always get feedback from people that own my work; someone who has lived with my work says, ‘Oh, it grew on me’. Especially in today’s time, where images are digested within fractions of seconds, it’s nice to hear that. My work has this element of digestion.

Andrew: We’ve talked a lot about this in terms of our work: starting with something that was wholly about design and drifting further away from that and then feeling like what we’re really doing now is more sculptural. You go back and forth between saying, ‘I don’t care, and people will feel how they feel’, and then needing to do some framing to help people perceive your intent.

Historically we’ve always had to compartmentalise ourselves in language and in order. I feel like the dialogue between art and design kind of lies between that. Sometimes when I go to bed I’m like, ‘I’m a fucking artist. I mean, fuck, fuck, fuck that client’.

Kristen: It’s like, ‘How dare you, trying to tell me what to do’.

Andrew: Yes, except all of the clients we’ve ever had, they’re great!

But it’s interesting how the dialogue with the client has changed, because of technology, Pinterest, and all these other things. I think a lot of clients think they could also design. I think for any designer or anything like that, it’s about creating a very bold aesthetic, where people come to me to get that.

Andrew: Maybe that, to some degree, accounts for the rise of the artist-designer thing. Because artists are considered to be these conduits for inspiration, and what they produce is unaltered. Designers are craftspeople that work with the client to make a thing. But if you are like an artist as a designer, then it becomes, ‘I’m going to design something, and you can’t alter it’.

Kristen: Blurring those two is pretty dangerous on some level. You’re really perverting both of those things by conflating them.

But at the end of the day, I feel like it’s about survival for the self. I’m thinking about making oil paintings. I’d love to make them in a year or so, and just make very large sculptures and small oil paintings. I don’t want to be the guy that was afraid to use yellow, or if I want to design a house, I’ll make a house, if I want to design a chair—

Andrew: You sort of say, ‘I will do whatever I want’, and then just be a person that’s living in the real world. And you determine the ways in which you navigate things and find the places where you do the things that you want to do.

Absolutely. Then there’s a public that might see you as an artist and others that see you as a designer. To be honest, coming from architecture and having left it in some kind of conscious way, and coming back to it through this other refreshed mindset, I’m perceiving it differently. So maybe the audience needs to perceive that. And it’s our responsibility, and I hate this. I’m not the most responsible person.

Kristen: Yeah. It’s like none of it matters, all of it matters. I don’t know.

Exactly. It’s terrible, but I think it’s about obviously attempting to do good work, number one. Number two: someone likes it, validates it.

Kristen: Number two: hashtag it.

Yeah, that’s number three. This is why I’ve never had that dialogue. As long as I’m in the studio and I feel like I’m awake and feeling good and there’s something that’s moving through me, if someone could sit on this piece and someone could fuck on it or someone could just look at it, I’m satisfied. No matter what that work indicates. If there’s something emotional that I might’ve been able to dictate and put into that, and that thing resonates and vibrates, then I’m satisfied.

close

close