Cornellà de Llobregat: One day, Guillermo Santomà sent me a DM on Instagram to say he really liked the book Raving by McKenzie Wark, for which I’d written the epilogue. Guillermo and I had only crossed paths once before that: I’d danced to some techno music at an installation he’d done for Matadero in Madrid, and a friend had recently told me about his intervention at a Gucci store in Milan. There was something pop conceptual and cheeky about his work that made me curious. While Guillermo is a well-established architect and designer with an eponymous studio, so much of his artistic practice emanates from other disciplines, so it’s impossible to pin him down. A few days before we met, I wrote to Guillermo to organise our meeting and see which projects he most wanted to talk about. Right away, he sought to redraw the boundaries and eschew the interview format; he wanted to be ambiguous in his answers, so we wouldn’t act out our typical interviewer/interviewee roles when we were in the studio. ‘We can talk for a while; it’ll be fun, and then you can edit it’, he told me. ‘Hahaha, laying down some guidelines for the interviewer’, was my response.

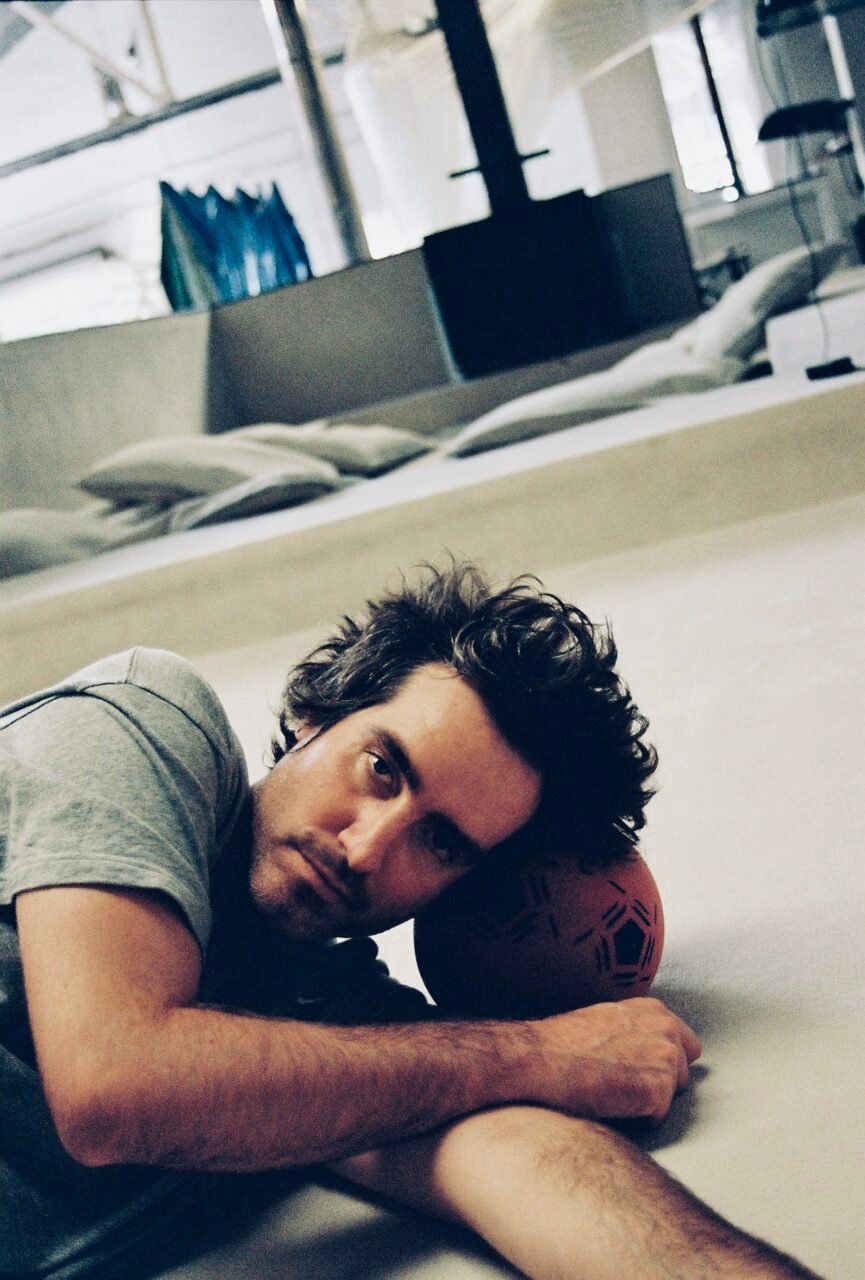

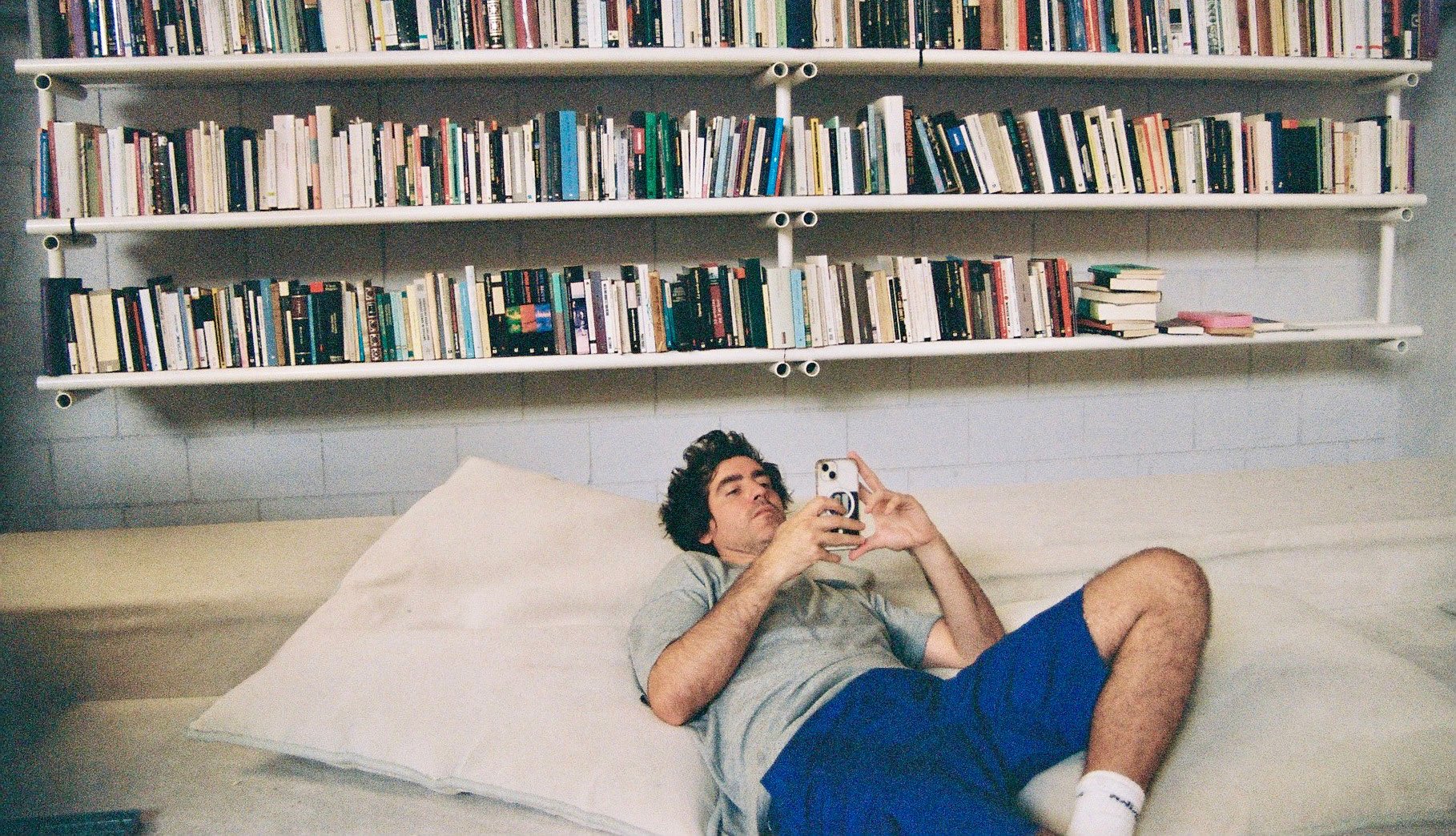

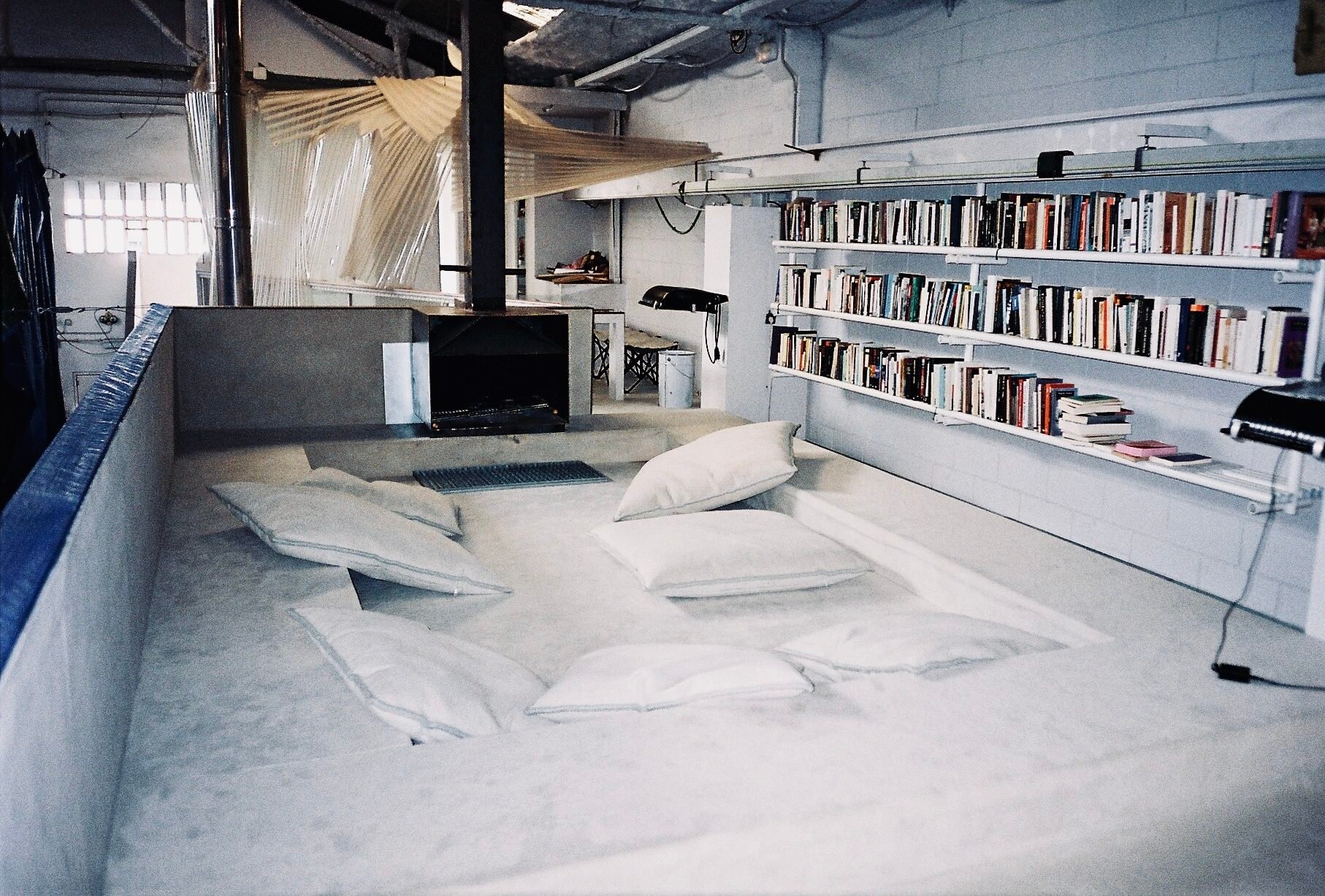

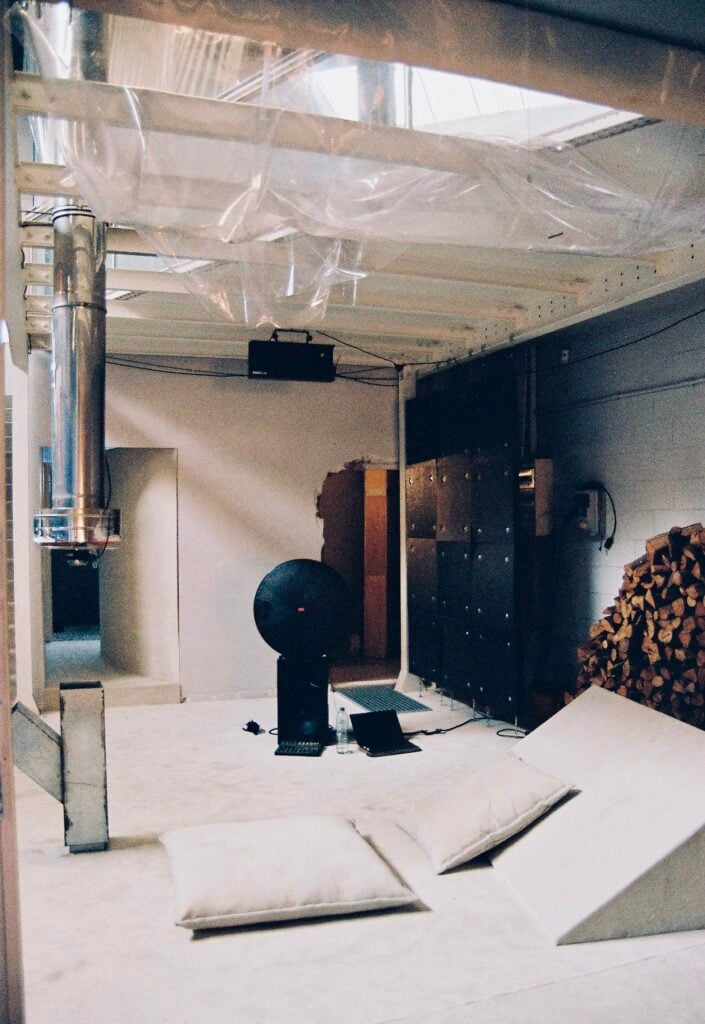

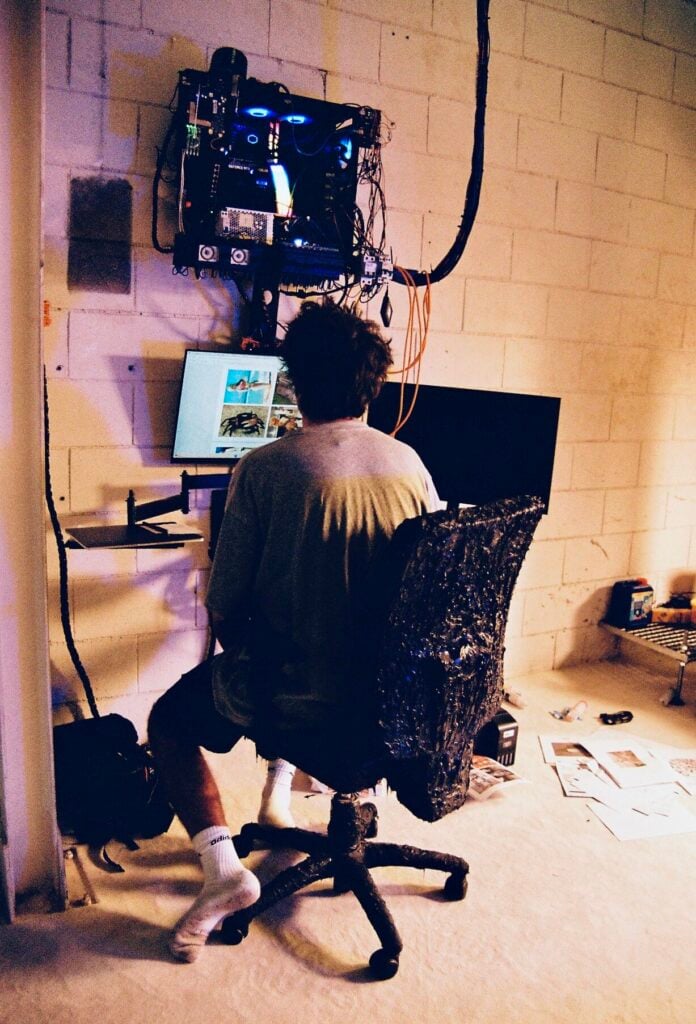

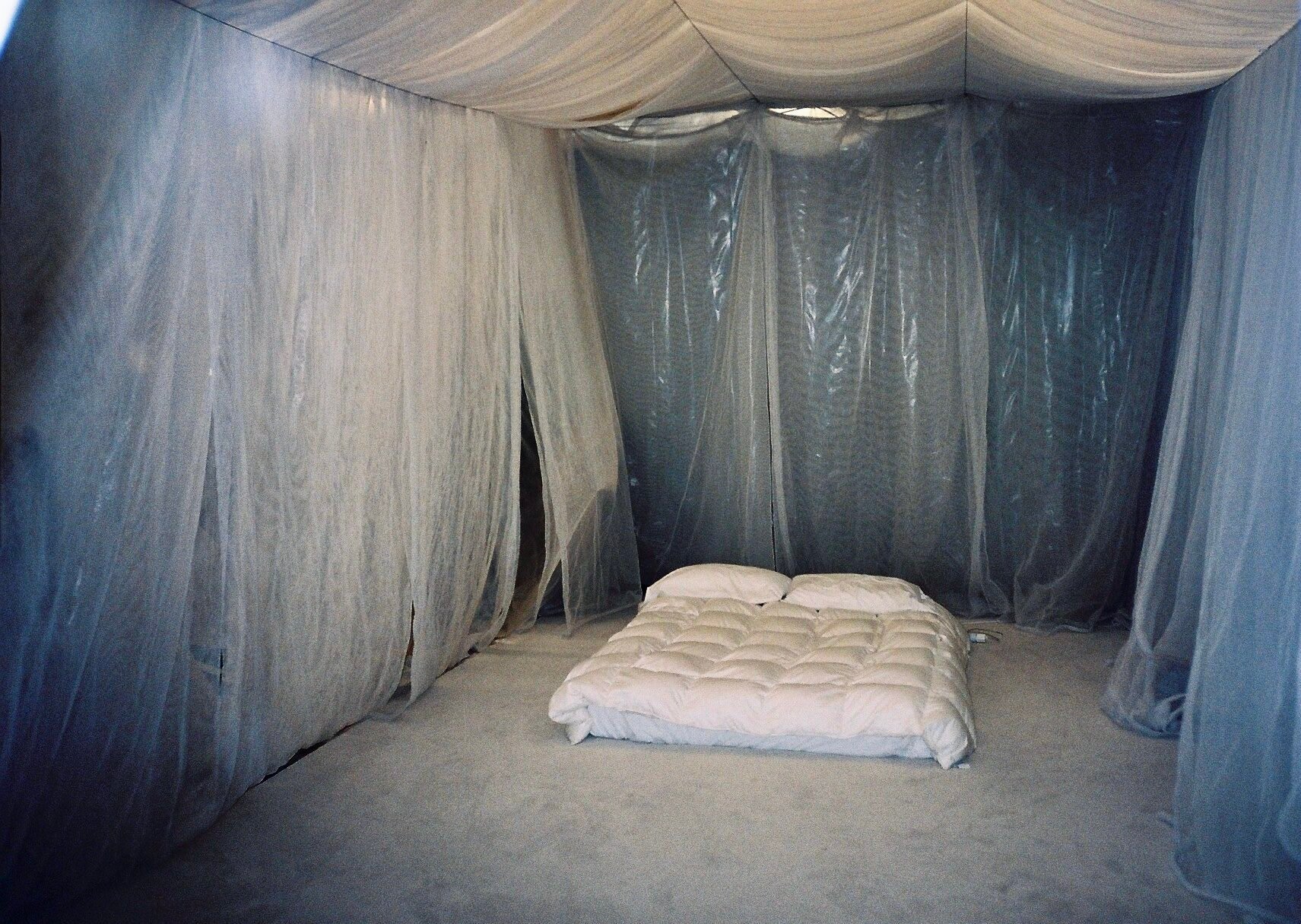

Guillermo’s studio is in Cornellà de Llobregat, a town to the southwest of Barcelona. I tell myself it’s worth the trek, and at least it’s safely past the Hospitalet area with all the gentrifiers. I’ve only gone to Cornellà a couple of times with a friend from the area to visit the bar owned by the parents of the rock group Estopa. I take the train, and, on the way, I listen to Charli XCX’s new album. I wonder what Guillermo thinks of the creative direction the album has taken. He quotes Yung Beef in one of his works, so I imagine he’s someone who listens to music while working. I want the interview to be amusing and punk, maybe even a little uncomfortable, but Guillermo charms me, and I never quite manage to turn the tables on him. We sit in the upper part of his studio in a kind of living room. I’m seated on some cushions in what looks like an empty, shallow swimming pool, next to a fireplace in front of a large, full bookshelf. I love to snoop around other people’s books, and Guillermo’s selection is arranged in alphabetical order. I like it enough to feel like asking for (or stealing) a book. I notice stains and burns on the light-beige carpet covering this playboy playground—I ask him about the wounded carpet, and he laughs and assures me he won’t be having any more parties. ‘I missed them’, I say, so he knows full well he owes me one. But that’s another story.

close

close