Video will be available again soon!

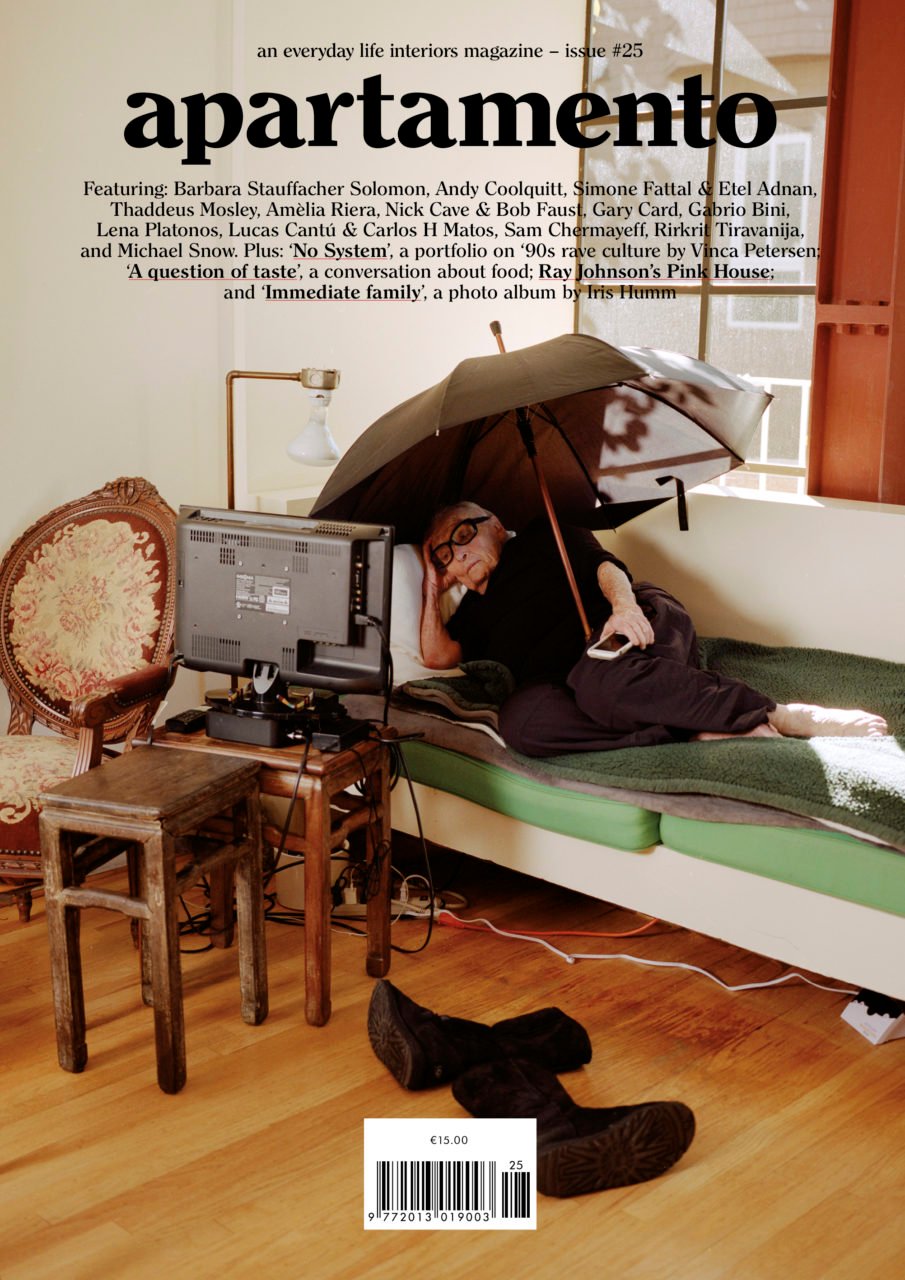

The following interview was originally published in Apartamento magazine issue #25, out now! Click here to get your copy.

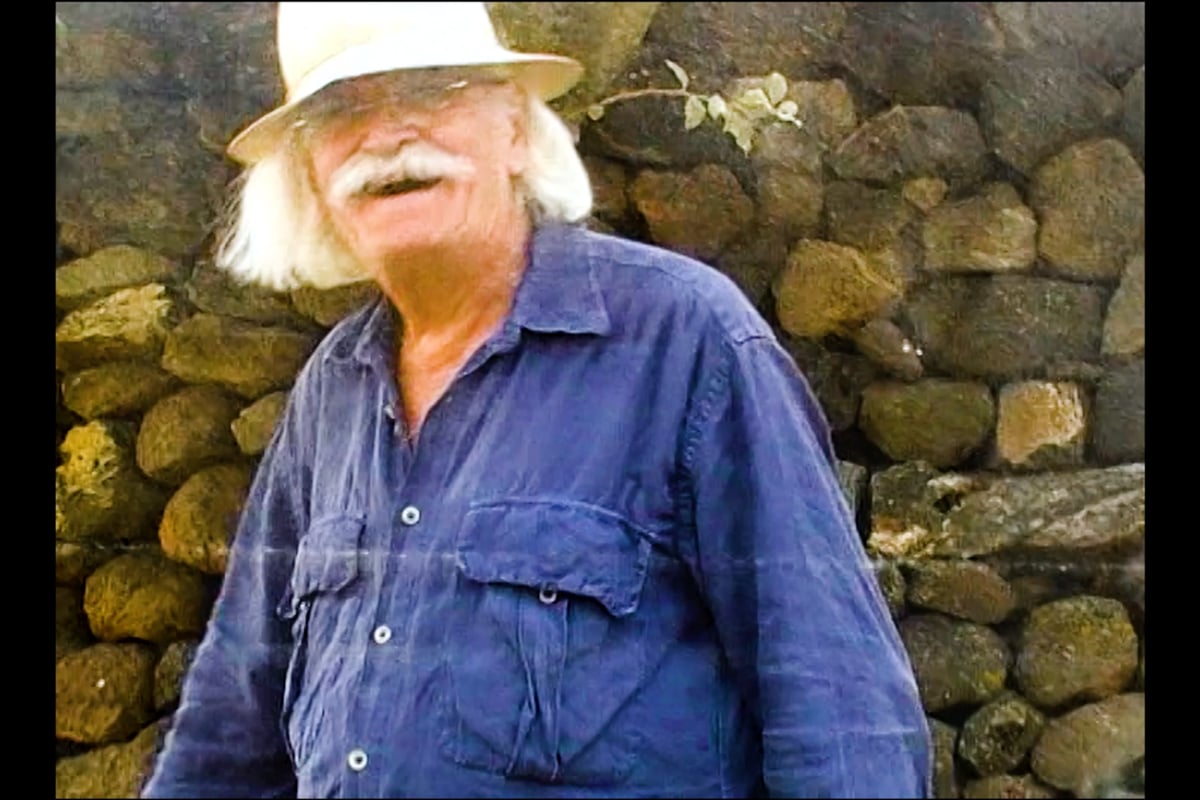

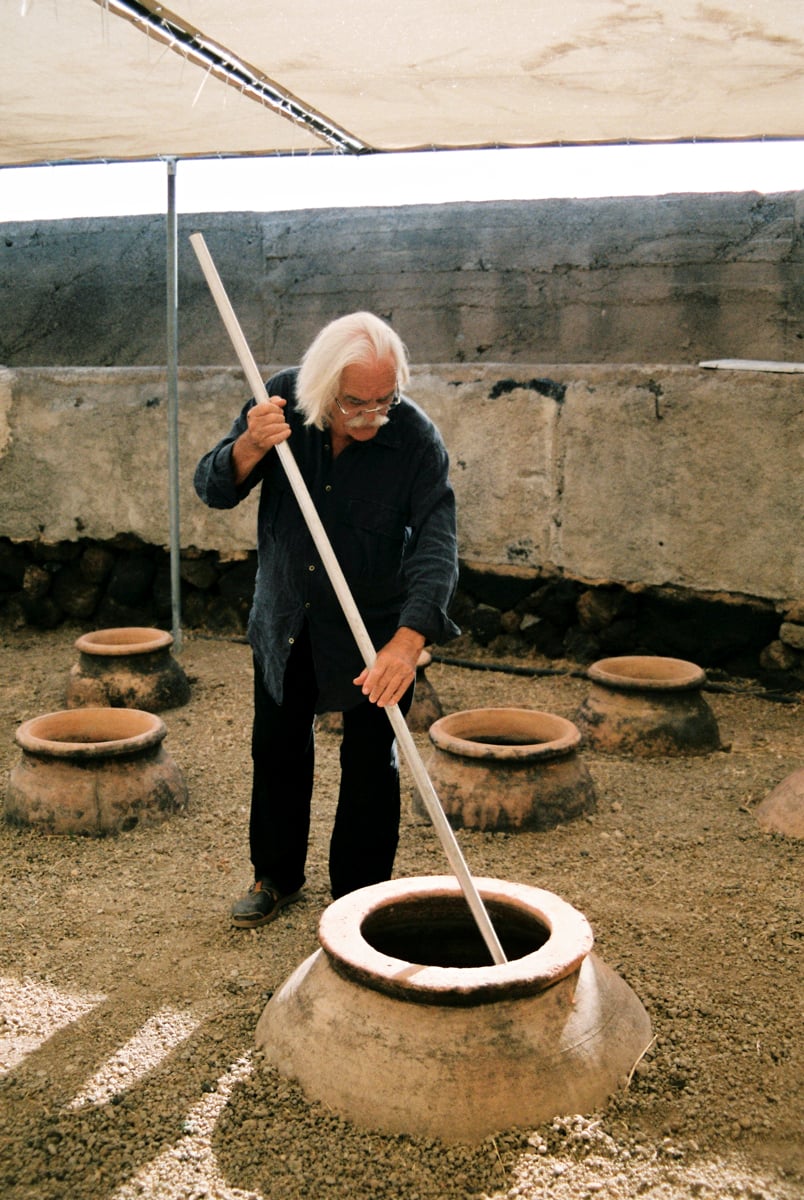

I first met Geneviève and Gabrio Bini at dinner in Pantelleria two years ago. They arrived at home with their dog, Agung, and a few bottles of their wine. I didn’t care much about natural wine then, and I still do not care about it much now. Unless when I remember what Gabrio Bini, who is originally an architect from Milan, told me one day: ‘People call this kind of wine ‘nature’, but just think of it as ‘natural’. It’s as simple as that’. As simple as that: such is the way I like to think of Serragghia wines, made by the three Gs: Gabrio, Geneviève, and their son, Giotto. Every time I thought of them, I remembered the deliciousness of their company as much as the deliciousness of their wines. The first time I took a sip of the Geneviève cuvée, I remember thinking something at least as stupid as, ‘This is so much more than wine’, when I also knew I couldn’t say a word or do anything, except maybe smile, to show Geneviève and Gabrio just how exceptional I thought their wine was.

I arrived on the island this year with friends who, unlike me, know their wine and who asked me if we could pay a little visit to the Binis. I had never been to their property and was happy to ask Gabrio, whose answer was simply, Y<3 OK <3Y. So on we went, driving up the hill from my house to theirs, with a feeling in our guts similar to that of visiting sweet yet distant relatives. Geneviève wanted to show us the garden, where we admired a 400-year-old bonsai tree. Gabrio had looked for a pot as old as the tree to replant it in. As he explained this to us, he also said that ‘all trees can be bonsais’. A sentence I’ve learnt to appreciate more and more as I spend more and more time with the Binis. Just as I’ve found myself using a word Gabrio Bini uses in every other sentence: ‘Fantastico!’

close

close