Read Anna Sulan Masing’s essay on the origins of laksa and the evolution of Peranakan cuisine in Penang: Recipes & Wanderings Around an Island in Malaysia.

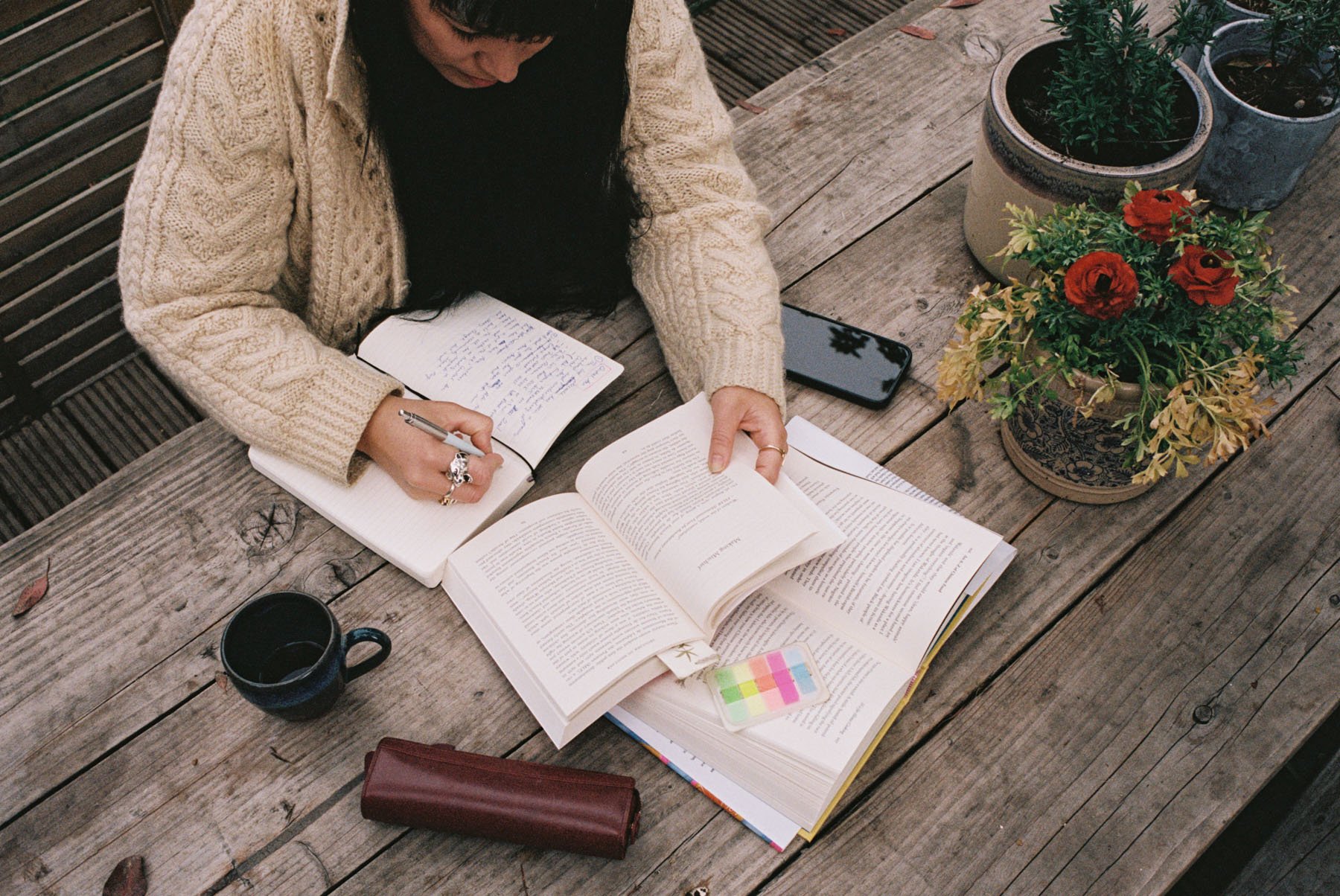

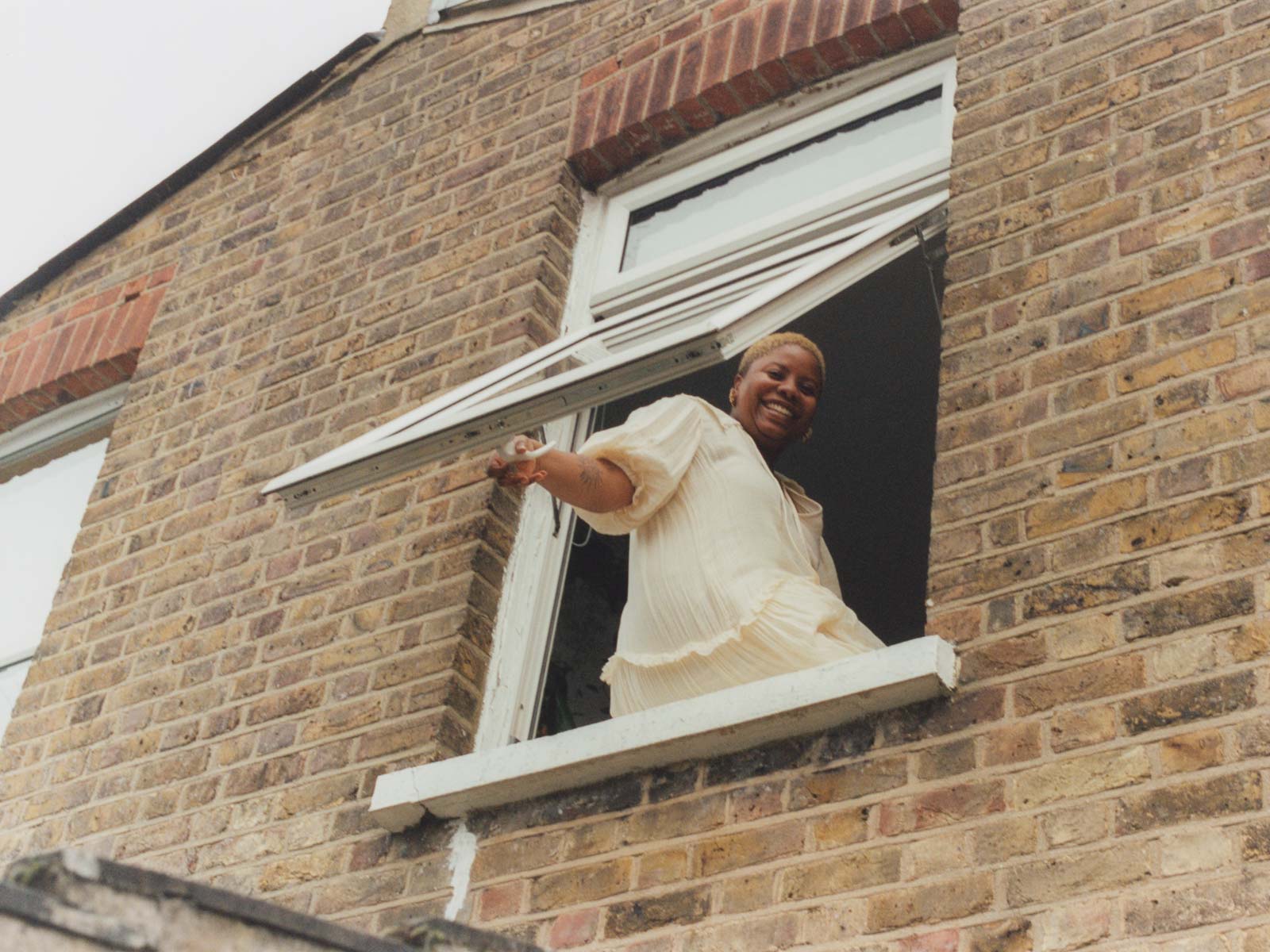

London: Anna Sulan Masing’s house in northeast London is like a repository filled with fragments of past and future works, whether written, spoken, or performed for a live audience. In fact, it’s hard to find a corner that isn’t covered with books, textiles, or ceramic treasures that either distil her own history, hint at a story she’s waiting to tell, or both. Being welcomed into a home like this is a treat; I give the living room a cursory once-over as she boils the kettle for tea, and the questions come easily.

As a writer, poet, and academic, Masing’s oeuvre largely revolves around food and beverage, her preferred avenues into complicated and often difficult cultural and colonial histories. Her latest milestone, the book Chinese and Any Other Asian, encapsulates this through an unflinching exploration of what it means to be East and Southeast Asian in Britain today.

Like her work, which is essentially storytelling through almost every conceivable medium, Masing herself is multifaceted. Born in Australia to a New Zealander mother of Scottish heritage and a father from the indigenous Iban tribe of Borneo’s Sarawak Island, she grew up in Sarawak, Malaysia, and Auckland before settling down in the UK. This upbringing primed her for her job, which sees her writing for publications and the stage, hosting podcasts, and launching public research projects and magazines. Masing used terms like ‘decolonising’ and ‘cultural appropriation’ long before they entered the mainstream lexicon through Twitter threads. She not only understands the intricacies of identity and our inclination, for better or for worse, to define ourselves and others through words, objects, victuals; she knows how best to unravel a bowl of steaming laksa, or unpack a single peppercorn, to reveal the crossroads and conflicts that lie within, which have shaped the ways we eat and the way we are.

close

close