Sam Chermayeff

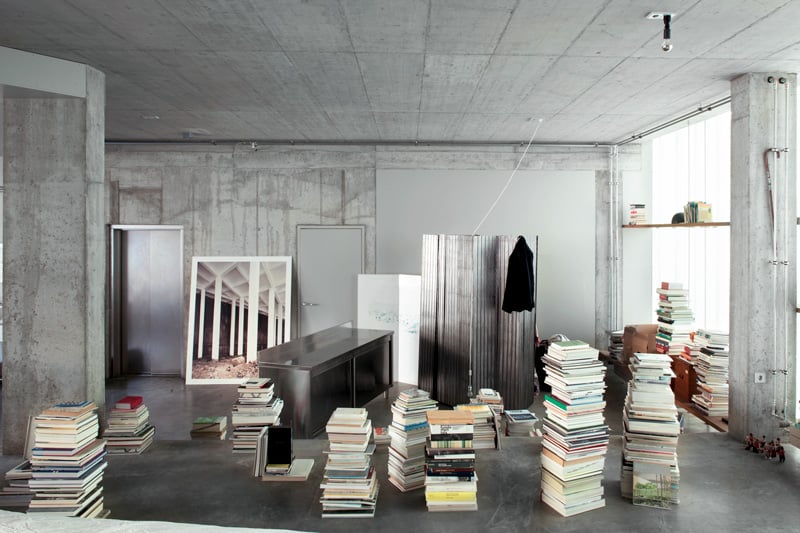

We spent a whole day with the architect Sam Chermayeff (NYC, 1981). We met at his office, which is in a concrete building designed by Arno Brandlhuber, with whom he shares the space. Sam used to live upstairs. There’s a quasi-monastic mood of silent work, but with cardboard models all over the place in a sort of organised chaos—you can definitely tell that something is brewing.You can find a model of a building next to a model of furniture. Neither seems more important than the other, and that’s precisely one of the reasons why we love his work. His approach is always the same, regardless of the scale of the object, and this vision is something we share. Actually, we share more than that, as we found out that the three people present in this conversation have an age difference of less than two weeks, in a kind of cosmic coincidence. Sam had a lamp he’d designed to be picked up, so we went together to the old workshop where a young team manufactures his pieces. It was huge and heavy. We brought it to the apartment that he shares with his wife Esra and their baby Ela, where we ended the day. It’s a classic Berliner building with high ceilings and double-wing doors colonised by his pieces and other beloved objects. There’s quite a lot to see, and a lot to cherish and take care of: industrial kitchen pieces, a coffee table, some pieces by Donald Judd and Kazuyo Sejima (better if you don’t touch that one!), and books on shelves and in stacks. There, we saw a copy of Sun Moon Star, a nativity book for children, written and illustrated by two atheists: Kurt Vonnegut and Sam’s father, Ivan Chermayeff. Ivan Chermayeff was America’s preeminent corporate graphic designer and son of the architect Serge Chermayeff, Sam’s grandfather. Sam has his own voice, and that voice has solid roots indeed. Before he prepared the most American dinner in town, consisting of Caesar salad and roast chicken, we had the pleasant conversation that follows in the living room.

Sam Chermayeff: We’ve been talking all day already, but I’m not sure about anything anyways.

Arquitectura-G: It doesn’t look like that; you don’t seem to be lost by any means.

Sam: Well, maybe I’m not lost, but things have come in an unintentional way. I’m only sure about one weird little thing, something that I think you share with me, which is the idea of an office. My father [Ivan Chermayeff: London, 1932–New York, 2017] was a corporate graphic designer, but he could have been anything. And he had an office. It was the notion of a place where things happen. The creation of that place as a kind of forum for thinking and making is really important to me. I like our team to understand me, and I like to understand them and to make a relation. I took two of them, Barbara and Betsy, out for dinner last night, had a huge steak, and stayed out until late. And that’s essentially my way of leading back to that almost 1950s idea of an office, in a Mad Men or Don Drapery way. What I make is almost secondary to that idea. So I’m not lost, yeah, that’s fair. I wish I could be more lost in many ways. I think of the office as an identity, so it’s not just routine. It’s like, ‘Who am I? I’m a guy with an office’.

A-G: You had an early and close relationship with design and architecture. Not only was your father there, but also your grandfather [Serge Chermayeff, architect: Grozny, 1900–Massachusetts, 1996]. We imagine you have childhood memories of his house in Cape Cod, meaning you had contact with good architecture even before you knew what that meant.

Sam: Yes, I totally cheated! My grandfather is who I’m closest to in terms of what I do. He wrote a book called Community and Privacy a decade before I was born. And I’m basically dealing with community and privacy; how do you bring people together? How do you make togetherness? He was really elegant, and also wild. And sometimes mean. He was a European. He cared about fabrics; he had a different sensitivity to that stuff. He was much more charming than my father, for example.

My father and my uncle [Peter Chermayeff, architect: London, 1936], who’s still around, were incredibly encouraged by him. They moved to America during the war, and my father became an incredibly successful graphic designer. He made the NBC peacock, Mobil oil, and so on. He wasn’t very interested in society; he was more interested in this idea of abstraction, which is the root of what I do. It’s really about, ‘How do you make a kitchen that is not a kitchen but is still a kitchen?’ I learnt the importance of this as a very, very young man. One of his best logos is Chase Bank. An octagon, a fucking blue, thick, abstract octagon. Basically, it has nothing to do either with banking or with Chase as a person. He and his partner, Tom Geismar, invented that idea. They also had the idea and did the logo for MoMA, rather than the Museum of Modern Art. When I think about both of them, I think that what I think is good comes from my father, but my pursuits are from my grandfather.

A-G: It’s interesting you mention MoMA and also your kitchens that are not kitchens but are kitchens, because in a way it’s the same thing. It’s no longer the Museum of Modern Art, but just MoMA, which is not a name but is the name. You grew up in New York, and you’re in Berlin now, but in the meantime you’ve been in a couple of places, notably London and Japan. You studied architecture in Austin. What brought you to Texas from New York?

Sam: Texas was as far away from Manhattan as you could possibly go. Tokyo was less far away. Tokyo was another centre of the world. Austin, Texas, is not that. I wanted to get into some other world. I am from the Upper East Side. In my class of 125 kids, 40 went to Ivy League schools, which is wild. I didn’t know what to do because I was not invited to do that. In Texas, I contributed to diversity, oddly. The idea was, and still is, to be among a bunch of other smart people with other points of view. Austin’s a free place, and kind of great. I really liked going to that school and having a practical education, learning how things get built. I got a little bit of that old man telling me, ‘This is how you do this thing’, like drawing a stud wall, and I learnt to care about that thing. I get such a kick out of it. And then I mess with it. I design with rules. I don’t understand how anybody thinks about design or about making things better if you don’t understand how things work. Design is about rules.

My own parents hired an architect while I was in Japan to redo their kitchen. And the fucking kitchen has, to me, two full-blown crimes: the sink has super hard corners on the inside, so you can’t clean them. And then—a terrible thing—the cabinet is flush with the counter edge. It’s an Upper East Side apartment, and it costs a lot every month just to have it, and you can’t clean the counter surface? You want toe kicks, you want to be able to clean the counter. The amount of kitchens that don’t have a place for you to put your hands to scrape crumbs is outrageous to me. You have to put it on the floor and wipe. Fuck you, world. In this particular regard, I’m such an old man. Basically I feel like I’ve been 68 in terms of soul age since I was 14.

A-G: Then you moved to London, but just for one year. What were you looking for?

Sam: Well, I thought that Europe—I thought the Architecture Association would be exciting. Funnily, I teach there now. And I was as confused about the same thing as a student as I’m confused about now as a teacher. So it’s weird that I try again. I was like, ‘Why aren’t we making floor plans?’ when I was a student. And as a teacher I’m like, ‘Why aren’t you making floor plans?’ Everybody looks at me like I’m out of my mind, just like they did then. Architecture is things, like walls, or, look over there, that gap between the floor and the baseboard. That bothers me. And that’s everything. But I am ashamed to bring it down to that. I just have to care about it, which is not to belittle all of the other thinking. I certainly care about thinking, but in the end I would like us all to better something physical. Dieter Rams is kind of the king of that. On some level, he made everything. It looks like he woke up every day like, ‘I’m going to make this thing better’.

A-G: After London you moved to Japan and stayed for five years. It was 2005.

Sam: Japan in the 2000s was the coolest thing ever. Japan, and particularly SANAA, was paring things down. Minimalism is a fraught term, but they had this new kind of minimalism that I basically still subscribe to. They tried to do something in a few moves and express it as simple diagrams. And SANAA was suddenly building diagrams.

When I was a student in Texas, Peter Zumthor was rocking everybody’s world. And Peter Zumthor is about some kind of pretentious sensuality, right? He’s great, don’t get me wrong. But you can have a client for a church in the Swiss Alps, and there are a thousand good answers to the question of how to make a little church in the Alps. Thousands. Whereas I felt like SANAA was trying to distil something down into a new universalism, which brings me to another whole world of problems—that universalism is also partly dead. In a way I got tricked by SANAA; I thought that architecture was universal. I thought, ‘Go to Japan and think about problems as if they’re everyone’s problems’, as if everyone can have the same universal answer, valid for Berlin, Barcelona, Paris, New York, and Taipei. I think the world believed in that, and they did a really good job of answering that call in every sense, and I’m really glad I went there. It’s nice to work for such an office when you’re young, because it’s endless work. I went home three times a week, which is to say, four nights a week I stayed in the office working. Really, all night. Obviously in an inefficient way, but it was great because you’ve got a commitment to rigorous thinking, and that is my education.

A-G: Given that learning’s so crucial to your career, when did you decide that that stage was finished?

Sam: The last thing I did was to curate the Architecture Biennale on Sejima’s behalf in Venice in 2010. It was by far the most fun thing I’ve ever done, before or since. I represented somebody who had just won the Pritzker Prize, and who also really trusted me. I could say and do what I wanted, which is awesome in the most basic way. At the time, it seemed like Berlin was the centre of the world, in a weird way. And I have a German partner, Johanna Meyer-Grohbrügge, so I came here to start our own office, June14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff.

A-G: How has that universalist mindset you brought with you evolved in Berlin over time? You’re working at a more local level now.

Sam: Actually, I have rather few clients of meaning outside of Berlin at the moment. I struggle to keep my clients in New York engaged at all. That’s when I think about your work with A-G and how it’s getting into this—having a certain architectural language related to the place you’re working in. We all grew up on Mies van der Rohe, on some level.

I don’t want to debate that, but Mies implies that everywhere is the same, the world is all one place. It is complicated, at least for me, to consider nationalism or more generously localism. But I understand that people want identity. I’ve been making all these things that are kind of anti-identity in favour of universality. And what clients want at their homes is context. What do you think about that? You are starting to build abroad, and yet everybody wants identity and context, right?

A-G: In a way, context is everything. We don’t really believe in universalism, but somehow we do at the same time. We don’t have a language of our own that’s so strong that it could potentially work everywhere; we don’t think we work the same way when we build abroad or in Barcelona.

Sam: I know you don’t, and I like that about your work. I struggle with this in my practice because I have a thing that I think works everywhere. I don’t know how I’m going to bridge that.

A-G: If you speak about objects or things—or creatures, as you call them—they are independent by definition, so the context is secondary, like a box you provide for them.

Sam: I’m aware of that. I think it’s the idea of cooking together which is universal. I mean, I believe in universality in my heart. In my deep soul, I totally agree with you. Otherwise I wouldn’t make what I make. But I also see that English is a thing, Spanish is a thing, New York, East Coast, West Coast. The styles and identities are real.

A-G: On a slightly different note: as far as we know, this apartment is at least your third since you came to Berlin. We know about your apartment in Arno Brandlhuber’s building, then another place with this industrial ceiling, and finally this classic, traditional apartment with high ceilings and wide double-wing doors. We’d like to speak about your relationship with Arno, as his architecture features in the background of many of the pictures we’ve seen of your work.

Sam: I’m friends with Arno from the craziest meeting of all time. We were organising something for the 2010 biennale and we invited Arno to a meeting. Sejima and I wanted to invite Thomas Demand to do something at the biennale, and he had this idea of doing a school about ideology, to recognise how ideology is buried into things. For example, that Slavoj Žižek thing about toilets. Let me digress about that. Toilets all over the world are different. Right? But on the other hand, everybody shits. It seems like it’s fundamental and not ideological: a toilet. Well, reluctantly, Žižek speaks about a 19th-century European trinity: the Anglo-Saxons, French, and Germans. In his telling, the Germans are about poetry and metaphysics. The French are about left, liberal politics. The Anglo-Saxons are the middle kind of rational. The Germans have the hole of the toilet in the front, so you take a shit and you see it and look at it. It’s like you understand yourself. It’s metaphysics, it’s poetry. Then you let it go. The French have the hole in the back. You take a shit, it’s like a guillotine, it’s gone. Future. Let’s move on. The Anglo-Saxons have a giant pool of water where shit just floats. It’s an in-between option, you can see it but can’t inspect it, and then it’s gone. It turns out that embedded in something as apparently utilitarian as a toilet is a political tool. Well, going back to that meeting, Arno and his colleagues were going to make a school, which seemed interesting, but then everything ended up in a big discussion with a curator screaming at Arno about all sorts of things that he had not done or said. Needless to say, the particular project never moved forward. I had led him into a trap by accident. One year later we met again by chance and I said, ‘Sorry, I owe you dinner’. That’s how we became friends. Then Arno and I had a crazy time where we hung out every day for two years. This was five years ago. It was full-blown, we really went for it without any caveats. Both of us had some personal situations, and somehow it happened. We talked about architecture every day. It was good. We still do, except we both have kids now, so we never talk about anything past 8pm.

Also, during these crazy two years some nice projects came up. For instance, the sauna. It is one of my favourite things, because it’s somehow a place and nothing at the same time. I made it as a vitrine for displaying something in an exhibition that we didn’t do. I put a door on and we made it into a sauna. It is so small in there that it gets really hot quickly. Then it became much more than that. As for my works that feature in his building, Arno makes shells and I’ve lived in one of them. He cares about universality in shells, as opposed to in programs. Everything that I do is somehow in minor opposition to that. It’s like I’m putting a bathtub against that concrete to say, ‘This is a place’. He had a particular amount of non-placeness. It’s really, really well suited to thinking about making place through objects. That’s what my apartment in that building was like.

A-G: Even if all the apartments you’ve lived in are different from one another, there are some pieces of furniture that come up here and there: tables, stacks of books, streetlights, kitchens. It seems that, independently of the shell, you have colonised those spaces in a similar manner.

Sam: I don’t have a clear answer to that. What I make works everywhere, right? For better or worse. I feel like most people who buy my things, including myself, are moving all the time. And you can bring your pieces of furniture with you. On the contrary, your work with Arquitectura-G is so not that. It’s built-in. It suggests you really live somewhere, and it’s just not my experience of the world, even if I’m deeply attracted to that—to the idea of, ‘I want to be here forever, or some kind of version of forever’. Whatever that means. I’m looking for some universal in living besides just place; you’re always going to need a light next to your coffee table. It’s not an invention. What is also true is that people are in constant movement. But I don’t like that. I want to be clear. I don’t think that’s good.

A-G: It’s neither good nor bad. When we do built-in stuff, it doesn’t imply that the people living there are going to live there forever. It’s more a question of the way we form a space. You can see pieces of furniture are in a space, whereas built-in elements, like spaces for seating, platforms, etc. are the space.

If you think about objects as independent pieces, as things that can be moved with you, it’s more about possession or a fetish thing. It’s of course also about beauty. By building in, you are speaking more about place rather than about objects.

Sam: Not only do I understand that, I’m jealous of that. I think that my transience idea leaves people empty, including me. I really want place, and I really want to build it in. Maybe I’ve been wrong by talking about universality versus a specific identity. You could easily compare that to your ‘place versus fetish’. I think you’re right about place. Maybe I myself am this synecdoche for globalism. Maybe now it’s time to just make a nice floor. I mean that literally, because that’s grounding. I think it’s worth it to try to be grounded, even if it’s temporary. In fact, it is. Maybe in the end we are both making buildings and our published work is a prelude to those projects underway.

A-G: One of the things we like most about your work is that we see you push some boundaries. Your objects have this sense of being kind of uncomfortable. Meaning they challenge the way people live and the conventions of what a table, a sofa, or a desk are supposed to be. Also, the thinness is very present in your work. They’re extremely slender pieces, delicate, and almost unstable, while being very strong at the same time.

Sam: It’s somehow a little bit accidental that things look like they are unsafe in the room. Maybe that is part of the discomfort, but the idea is not to make anybody uncomfortable. I want things to read typologically and ideologically, apropos the Žižek toilet thing, to read as something clear and therefore comfortable. So, you understand that a sofa’s a sofa. It’s not just a thing you can lie on, like a pile of soft things. I want it to be a sofa.

A-G: We would like to go through some of your pieces and the stories behind them. Let’s start with the triangular bed.

Sam: It started from a really simple thing. It started relationally. I was in love with somebody but living with somebody else. My sense of place was appended, and so we made it, at the very beginning, as if it were a symbol of that appended-ness. Then it turned out to work really well.

A-G: So it’s a metaphor or a symbol? The love triangle.

Sam: Not at all. It was never a metaphor. It was in a thing that was not a rectangle metaphorically speaking. Suddenly I was like, ‘OK, let’s try to answer this in some other way. I called it ‘for the nuclear family and its opposite together’, which is just about trying to work something out. I made one as my contribution to an exhibition about the future, which was called ‘This Is Tomorrow’. Basically, I then took it home, started sleeping on it. It works really well. You can sleep in a whole bunch of directions, you have sex in a whole bunch of directions. Now we have a family, so I have experience on all levels in a relatively short period of time, and it’s so nice to have one end of your bed wide, and to have our daughter in the middle or on the side. Also, when you put it in a regular rectangular room, the spaces leftover are the best, even better than the bed. As it’s a triangle and the room is rectangular, suddenly they can be liberated and you actually have more free space to walk around.

A-G: Besides the bed, you have also proposed this stunning set of separate objects that make up a kitchen, breaking its conventional, more monolithic shape.

Sam: It’s crazy that we make kitchens in lines. It’s only two generations back that it was decided that kitchens are 60-centimetre lines off the wall. That’s fucking outrageous. You can’t really change it, because a dishwasher is 60 centimetres deep. That’s defining everything? Just think about it. Think about how crazy that is. Think about how many linear metres of bullshit kitchens exist in the world. It’s like, ‘Let’s stare at the wall, we’ll talk about architecture in the living room?’ How did that happen?

A-G: We’re all victims of the Frankfurt kitchen. But domestic kitchens are not factories.

Sam: In a way, as you say, everything became a factory. So many things became factories that we don’t understand, and we still value the idea of efficiency as something good. Like smart cities, where they tell you to go to a restaurant that they think you’ll already like. That’s my idea of hell. Yet I live in that idea of hell. It’s just a set of roles that we play. The force of those roles in our lives is huge. Just endless.

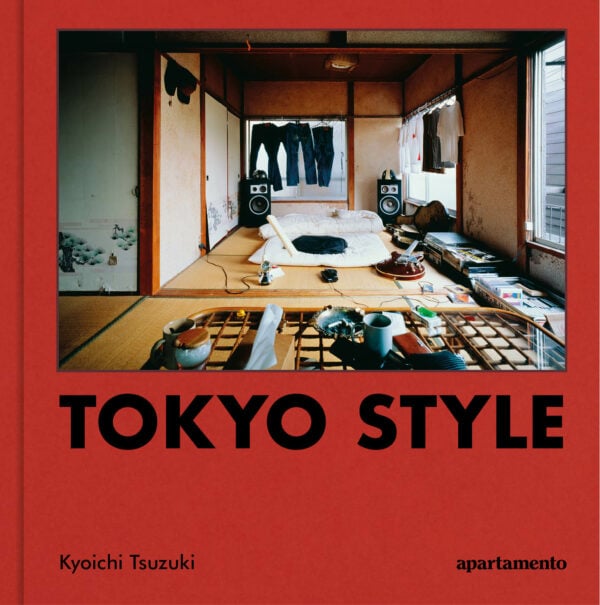

A-G: Yeah, but talking now about books, as we’re surrounded by them, how many 35-centimetre shelves are there in the world? It’s the best or the most efficient way to find a book, but it’s such a beautiful image to see your stacks of books, all in piles, colonising the space. Taking the one at the bottom is challenging though.

Sam: You say with way too much conviction that those shelves are the best way. I’m fairly sure that that’s the best way. But it bears repeating that what is standard and seems efficient might not be. For instance, I put the books I like or the ones I read often at the top of the stacks. If you work at it time by time, you will come upon a thing that is better than the standard.

Again, I’m not looking for the Pritzker Prize. I just mean, can you believe that there’s an almost infinite number of coffee tables, and not one of them lets you make coffee on it? It’s called a goddamn coffee table, so how can that be? Nobody has time to rethink everything all the time, including me. But it is incredibly rewarding when you occasionally hit upon that. Despite the fact that I, as a young architect, thought about the free organisation of place, I also think that being settled is a kind of freedom. If we accept the idea of free placement, then the idea is that it doesn’t have to be a room, and, speaking about kitchens again, you certainly don’t have to face a wall. I know that’s not even especially original as an idea. It’s not like I reinvented the kitchen island. Somehow, my kitchen does something else. It allows you to constantly reorient yourself, with yourself. You go and sit down, you go toast at the toaster. You toast something. We toast. That thing, which is suddenly like a body, like a creature, is just a metal stand with a toaster. You are talking with the toaster, and the toaster is somehow talking back to you. You’re in a dance with that toaster. It’s like all the kitchen things, in some way, are in a dance. You measure yourself; you measure it. It is bordering on esoteric and a little bit hard to articulate, but I think that you think about yourself, what you’re doing, why, who you are, what this is, what the toaster is, what kind of toast, how hot, yada yada, how many seconds, in a totally different way. Because the world is full of appliances. In the end, we carry our phone all the time. It’s all essentially a big giant appliance, but it’s also nothing. There is no value. It doesn’t tell you anything about yourself; it’s impersonal. You make that stand with a toaster, and suddenly you value it. It’s so nice to deal with things that you’ve agreed to value.

A-G: Putting the appliances on top of pedestals for practical reasons also makes them less mundane, like a piece of art that has a distance from the ground. We’re not saying you’re worshipping the toaster, but you’re definitely putting it into another dimension.

Sam: But you do want to worship your toaster. Why not worship it? Yeah, I want to worship things. You are in my and Esra’s house, and we clearly like stuff.

A-G: It’s obvious you like objects. We can certainly see you collect items that are important to you, whether it’s a piece of stone or a drawing. What does an object have to have to stay with you or to be loved?

Sam: You’re not seeing the full extent of my stuff. I keep every ticket for every movie that I ever went to see. There is a very low standard, let me be clear. Everything has value. I save everything. But I’m not a collector. It’s an incredibly vain notion that somebody’s going to care later. I don’t really know. Marie Kondo’s an idiot. I think that all things are stories with potential. All you need to do is decide that it’s loved. That’s the whole point of all the work. Like this table with a shitty streetlamp. We can walk around the corner and find the same streetlamp. We take it for granted. It’s there. It’s nothing. It’s so great to suddenly turn something that’s meaningless into something with meaning, and I like that you can just do that. It’s like you exercise a power. I feel like not enough people understand that all they have to do to like something is to like it. Then it becomes nice. You can make anything nice in a weird way, which is also why Ikea is difficult. It works well, it’s efficient, it’s cheap. But you can’t put meaning into it. I’m trying to make and think and live in such a way that I can put meaning into it. I think you can make space and place with objects on a ground level. It turns out that there’s a tremendous amount of opportunity, if you’re in a temporary state, to do that. I couldn’t have changed any of those houses and made place in the built-in sense of your work, just on a technical level. I like shelves. I like living in places that are like shelves, where you can have absurd spaces that you don’t need. There’s a lot of luxury in bullshit. In things that don’t make sense. Then you make sense with yourself in the toaster, and then you turn to your left and you see an empty office, and those two countervailing forces lead you to some kind of balance in your life. Does this make sense?

AG: It does.